RevolutionsPodcast Well, you can wait 10,000 years for the Proletariat to develop their revolutionary consciousness through Workers Education and propaganda, or you can listen their greivances, write them up in a pamphlet and use them to agitate. And that’s just what Lenin and Martov were happy to do in Episode 10.23 On Agitation. In Episode 10.24 The Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class,Lenin travels overseas to meet the exiled revolutionaries from the 1880s. For a little while he, Plekhanov and Martov are all on the same page- that the revolution in Russia must be led by Russians, not exiles fro outside Russia, and that agitation is the way to go – but this unanimity isn’t going to last.

The Reith Lectures 2016 Okay, so I’m a year or two (or three or four) late. In 2016 Philosopher and cultural theorist Kwame Anthony Appiah delivered the 2016 lecture series “Mistaken Identities”, with each of the lectures rather neatly starting with “C”. In Creed, he argues that religions have always claimed a stronger authority for their sacred texts than they actually have, and that a religion’s reading of so-called ‘unchangeable’ scripture changes from time to time, in the light of the present. In Country, he suggests that people sign up to a shared set of beliefs, institutions, procedures and precepts and this (rather than a mythical and romanticized view of nationhood) is what binds them together. His Colour lecture was recorded in his birthplace, Ghana, where he tells the story of Anthon Wilhelm Afo Afer, brought to Germany from the Gold Coast as a child in 1707n who became an eminent Enlightenment philosopher. He was a living challenge to the idea of a ‘racial essence’.

The History Listen (ABC) 20 October 2019. Right now Bradley Edwards is facing trial for the Claremont Killings, at least three killings and disappearances that took place in upper class Claremont between 1996-97. This episode Claremont: the murders that rocked Perth is not so much about the current trial, as about the two other men that police thought had committed the crimes. Twice the police thought they had “their man”, only to ruin the lives of innocent men they accused.

Outlook (BBC) 12 September 2019. Another old episode rattling round on my phone.I Raised 1000 Children But Gave My Own Away is about Indian activist Sindhutal Sapkal, who was married off at the age of 10, and at 20 and heavily pregnant, was bashed unconscious by her husband. When she recovered consciousness, she had given birth to a daughter. Escaping her violent marriage, she became aware of hundreds of abandoned children, and took on their care as well. Despite her own feeling of abandonment by her own mother, she enrolled her daughter in a boarding school. There’s a surprising spirit of love and forgiveness here.

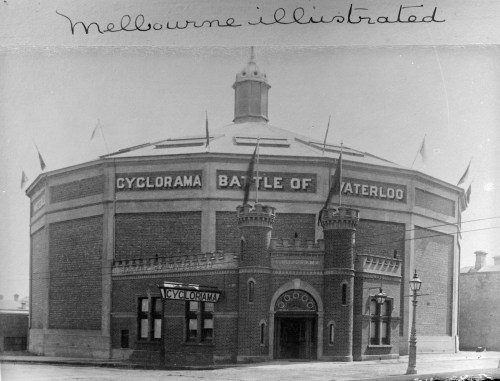

Birkbeck Institute. You can access seminars recorded by the Birkbeck Institute, and I always enjoy hearing an Aussie accent there. In this lecture, recorded in November 2017, Alison Moore from Western Sydney University talks on Morbid Love in Late Nineteenth Century France. L’amour morbide – morbid love – was an umbrella term for a number of pathologies including frigidity, inversion, fetishism, nymphomania, sadism and masochism. ‘Morbid love’ was of great interest to psychiatrists, especially in relation to degenerationist thought, and the literary works of writers like Stendhal, Zola and Wilde. By the end of WWI this interest had spread into low/middle-brow culture, and is was no longer of interest to psychiatry. These lectures are very low-tech and often theoretically complex- a bit like sitting in a seminar where you’re straining to hear the audience questions. Nonetheless, very ‘meaty’.

Birkbeck Institute. You can access seminars recorded by the Birkbeck Institute, and I always enjoy hearing an Aussie accent there. In this lecture, recorded in November 2017, Alison Moore from Western Sydney University talks on Morbid Love in Late Nineteenth Century France. L’amour morbide – morbid love – was an umbrella term for a number of pathologies including frigidity, inversion, fetishism, nymphomania, sadism and masochism. ‘Morbid love’ was of great interest to psychiatrists, especially in relation to degenerationist thought, and the literary works of writers like Stendhal, Zola and Wilde. By the end of WWI this interest had spread into low/middle-brow culture, and is was no longer of interest to psychiatry. These lectures are very low-tech and often theoretically complex- a bit like sitting in a seminar where you’re straining to hear the audience questions. Nonetheless, very ‘meaty’.