2016, 177 p. plus notes

I admit that it might seem rather perverse to read about polio epidemics during our own coronavirus pandemic. But with the government’s attempt to highlight COVID infections amongst younger people as well as in older populations to highlight the seriousness of the situation, my mind has been turning recently to the polio epidemics of the past, and particularly the significance of age during a pandemic.

My father was the second child of the family, with a much older half-brother born to a previous marriage (as was too often the case, my grandfather’s first wife died in childbirth). Effectively brought up as a much-doted only child, my eight-year old father was sent to the family property up in Healesville to stay with his grandparents when the polio epidemic of 1937 struck, far from the contagion of the city.

My father with his father (left), grandfather and mother at Healesville

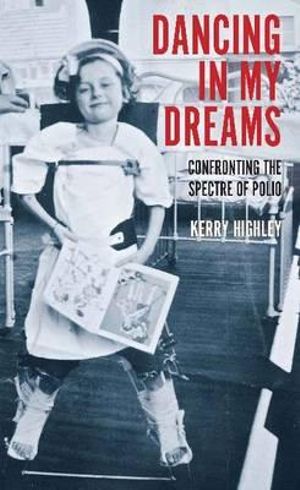

Through Highley’s book Dancing in My Dreams: Confronting the Spectre of Polio, I now know that the government tried to discourage parents from doing exactly this, no doubt fearful of spreading polio even further. The streets in 1937 were deserted, she writes, and the picture theatres empty. Schools were closed, and states rushed to close their borders, something that the Federal Minister for Health, Billy Hughes, declared was unconstitutional. (Federal politicians obviously don’t like to be reminded that state borders still exist.) I still shake my head in disbelief that I have seen the same thing in 2020.

But, in fact 1937 was not the most virulent polio epidemic that Australia has seen. That distinction belongs to the early 1950s, when polio affected 32.30 in every 100,000 of population and affected states across Australia (compared with 14.10 in 1936-40, which mainly affected Victoria.) Nor was it necessarily infantile paralysis, as it was more formally known. The improvements in sanitation in the early twentieth century meant that very young infants, who seemed to be less severely affected, were less likely to catch it. Instead, older children from about 6 and up, teenagers and young adults contracted it. In European, industrialized countries, it changed from an endemic disease to an epidemic one, and one that affected middle class children and young adults, and not just ‘the poor’.

Epidemics prior to 1951 affected particular states, rather than the country as a whole. In 1904 it was Queensland and NSW; in 1908 Victoria; and then in New South Wales in 1931-2. During 1916 New York was afflicted with an epidemic that evoked many of the public health responses we have seen recently: six (!!) weeks quarantine of patients and contacts; food delivered to the front door, funerals held in private, schools closed, public meetings banned. The public perception that there was a correlation between polio and dirt was challenged when Franklin D. Roosevelt became President. That myth may have been crushed, but the perception that to be “crippled” (to use the terminology of the day) was a matter of shame continued for decades.

During (and after) the 1937 epidemic, there were two competing treatment regimes and much of Highley’s book describes the personalities, history and politics that affected the dominance of one regime over the other. These clashes took place within a particular historical context. The 1908 Medical Act established the dominance of the medical profession over the chemists, dentists, midwives, herbalists and homeopaths who had operated in the medical sphere previously. Nurses, although trying to emphasize their professionalism through groups like the Australian Training Nurses Association, were very much under the control of doctors and the British Medical Association in Australia organization was very powerful. Interestingly, due to the influence of Christian Scientists and chiropractors in the United States, this strict delineation was not a feature of the American medical scene. In Victoria, the ‘fever hospital’ (later Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital) opened in 1904, and in 1937 all polio cases were sent there.

The official response was headed by Dr. (later Dame) Jean Macnamara, who graduated from the University of Melbourne in the stellar year of 1922 (along with pediatrician Dr. Kate Campbell, hematologist Dr Lucy Bryce and medical scientist Dr (late Sir) Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet). She was appointed resident of the Children’s Hospital the following year, then became clinical assistant to the Children’s out-patients physician and entered private practice specializing in poliomyelitis in 1925. When a polio outbreak occurred that year, she began testing the use of immune serum in her patients and continued to do so even when other international results called its efficacy into question. (Another resonance today- serum is being tested for COVID as well.) Her method involved the splinting of children into a Thomas Splint – a flat, almost crucifix type structure- for months if not years until the damaged nerves had recovered. Her preference for splinting also extended to treatment for knock-knees and postural problems. In Highley’s somewhat critical depiction, she took a rather utilitarian view of illness, with an emphasis on the economic costs of the ‘cripple’ who would need an invalid pension in the future.

The competing treatment was pioneered by Sister Elizabeth Kenny, a nurse – not a doctor- from Townsville. Instead of waiting for the inflammation to subside, the Kenny treatment involved hot flannels for the pain (something that Macnamara’s treatment did not prioritize) and early massage and manipulation of the muscles. As Highley points out, Kenny was in many ways her own worst enemy. She was evasive about her own background, which did not include general nursing training, and it was her experience during WWI that qualified her to call herself ‘Sister’. She was adamant in distancing herself from what might be construed as ‘quack’ medicine, which meant that she did not ally herself with the increasingly-accepted discipline of physiotherapy, which probably would have been to her advantage. Not part of the medical establishment Kenny herself was pugnacious and often alienated people who could have assisted her. Her methods were more accepted in America, where the medical establishment did not have the same stranglehold, and in New Zealand. Although some of her methods were integrated into Australian treatment, the Kenny-dedicated clinics dwindled, and ‘Kenny-like’ treatments diluted the significance of early intervention.

So much was not known about polio at the time: how it was transmitted, its effect on the body, the prognosis for an individual. Just as today, there was a frantic race to find a vaccine against polio, and the tragic mis-steps in this process bring a note of caution to our current world-wide race to find a COVID vaccine.

But the focus of this book is very much on the individual, and his or her experience of polio. She traces through the diagnosis and early crisis of the disease, the responses of child and adult patients to this rupture in their lives, the differing experiences under the Macnamara and Kenny treatment regime, the long period of rehabilitation and family and societal responses in the years and decades afterwards. The text has liberal quotations of oral testimony, drawn from a variety of sources, and you never forget that you are reading about people. It is engagingly written, with equal attention to personality, politics and science.

And no, it wasn’t depressing reading during a pandemic. It was oddly reassuring to read that communities had been frightened by a disease that was unknown, and that the current measures of quarantine, isolation and, yes, border closures are not some 21st century draconian infringement on our liberties or a conspiracy dreamed up on the edges of the internet. It was interesting to see two women competing within the medical sphere, and the power dynamics at play. There were mis-steps and misapprehensions, but knowledge of polio as a disease gradually expanded. The book captures attitudes towards illness and disability that are best left in the past. The story of the polio vaccine and its tragic failures prompted by haste carry a warning (I’m speaking to you, Trump), but eventually confirm the importance of vaccination and rigorous testing. I’m glad that I read this book.

My rating: 9/10

Sourced from: read online through State Library of Victoria.

I have read this as part of the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2020