1996, 176 p.

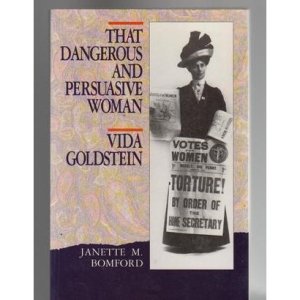

As I might have mentioned once or twice, I’ve been involved in a street opera project called Serenading Adela. This event commemorates the centenary of the march of about 300 women to Pentridge Prison on 7 January 1918 to sing songs to anti-war activist Adela Pankhurst, who was imprisoned there on charges arising from a speech given on the steps of Parliament House the previous year. The Pankhursts were a well-known family involved in the fight for women’s suffrage in Britain, but Adela’s political history went beyond that in Australia. She had been sent to Australia by her mother Emmaline in 1914 on a one-way ticket with twenty pounds, some woolen clothing and an introduction to Vida Goldstein, whom the Pankhursts had befriended back in 1911.

In Australia Adela Pankhurst was well-known as a speaker against war and conscription, a member of the Victorian Socialist Party and a foundation member of the Communist Party of Australia. From that she moved to the Australian Women’s Guild of Empire, and from there to the far-right Australia First movement. She was interned following the bombing of Pearl Harbour. for her pro-Japanese sympathies in World War II. While this shift from the extreme left to the extreme right is not uncommon, it does seem bewildering. Lives are rarely lived randomly, and biographers look for a unifying thread, some continuity in world-view that makes sense to their subject, no matter how inchoate it may look from the outside. So how does Verna Coleman characterize Adela Pankhurst?

A clue can be found in the subtitle: “the wayward suffragette”. The first third of this book deals with Adela’s life in England, as part of an intellectual, politicized family dominated by her mother Emmeline and her eldest daughter Christabel. According to Coleman, Adela became increasingly uncomfortable with the militancy, violence and extreme feminism of the suffragette campaign, even though she herself was involved as speaker and activist. After a physical and emotional breakdown, and ensnared within the jealousies of her sisters, Adela left the suffragette battlefield and acquiesced to her mother’s demand that she not speak in public in Britain again, and agreed to go to Australia instead- just about as far away as she could get.

Adela arrived in Melbourne in March 1914 and was immediately welcomed by Australian suffragists. She spoke out as a pacifist right from the start of the war, and sympathized with Germany as the underdog dominated by Britain and France (p.63)- a rather dangerous stance at the time. She was welcomed into the pacifist socialist group that was drawn to editor of the Socialist, Robert Ross; a group which included Bernard O’Dowd, Jack Cain, John Curtin and unionist Tom Walsh. Pankhurst was to marry Tom Walsh, and together they moved politically across the spectrum from communist to anti-communist. It is rather galling to see that Adela’s entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography is shared with her husband Tom Walsh, with his lifestory told first. One would have thought that she deserved a stand-alone analysis.

Many of the chapters of the book- but not all- start with a fictionalized, italicized word-picture of Adela. It’s an interesting touch, and I was disappointed that it was not sustained throughout the text. Coleman draws on Adela’s own autobiographical writing, letters in the Pankhurst-Walsh and David Mitchell archives, and newspaper articles.

Coleman’s book traces Pankhurst-Walsh’s philosophical and political shifts, but although she recounts the trajectory, she does not very well explain it. Analysis comes in a short chapter near the end of the book titled ‘Renegade, ratbag…or romantic enthusiast?’ In these few pages, she suggests that perhaps Adela tried to recapture the romantic fervour of her youth, constantly needing excitement as she shifted from one cause to another. “Like many a reformer”, Coleman states “Adela was driven by egotism as well as by altruism”. However, the adjective “wayward” in the title seems infantalizing and I don’t think that it does Pankhurst justice as a political actor in her own right.

In an article in Australian Historical Studies (25, 100 p.422-436) from 2008 called ‘The Enthusiasms of Adela Pankhurst Walsh’ Joy Damousi does a better job, I think, of detecting a coherent thread throughout Pankhurst-Walsh’s political journey. It was concern for children growing up in slum conditions, Damousi suggests, a concern that could be just as easily (indeed, more) accommodated in the politics of the right as of the left. Once I read Damousi’s article, I saw that Coleman has in fact referenced this abiding passion of Pankhurst’s throughout. But by characterizing her as the ‘wayward suffragette’, Coleman highlights her deficits as a ‘wayward’ Pankhurst daughter rather than as a thinker of agency with a continuity of passion that took her from one extreme of the political spectrum to the other.

This will be my final review for 2017 for the Australian Women Writers Challenge. I’ll be back in 2018 to start the challenge all over again.