It’s literally the first Saturday of the month, which makes it Six Degrees of Separation day. This meme, hosted by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best involves Kate nominating a book I have rarely read (in this case, We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson) and then nominating six other titles of books that spring to mind.

- With ‘castle’ in the title of the starting book, what else could I go for but I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith? In Grade 7 and 8, I just loved this book and kept reborrowing it from the school library. I saw the film, but it didn’t have the magic for me now that it had as a young girl. I have a copy on my shelves, but I don’t know if I want to re-read it or not. Perhaps some books are best left as memories.

- Brideshead Revisited had a castle in it too. I loved the series with Jeremy Irons. I know that I read the book too, while I was at university.

- L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between was set in a big house as well, told from the perspective of a visitor from a lower class who doesn’t know the ‘rules’ of the gentry. We read it in Matric (yes, I’m that old), and I think that it has one of the best starting lines in literature: “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.”

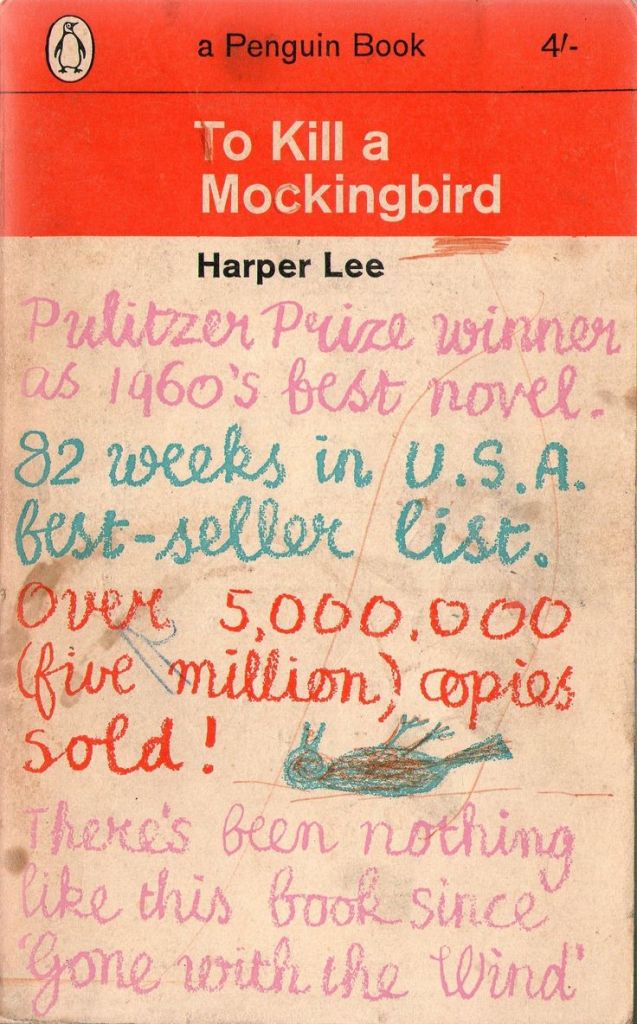

- Like everyone else in the world, we read To Kill a Mockingbird at school too. I have re-read this one, many times, and every time I hear the music to the absolutely perfect movie, my eyes fill with tears. To me, this book is emblematic of the Deep South

- Another book set in the South- New Orleans this time- is The Yellow House by Sarah M.Broom (my review here). The youngest of twelve children in a working class family, she tells the story of her family home in New Orleans, interweaving national and local history, family stories and her own story of place and identity.

- The Lives of Houses, edited by Kate Kennedy and Hermione Lee is a collection of essays that emerged from a 2017 conference titled ‘The Lives of Houses’ held at the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing at Wolfson College, Oxford. This conference brought together scholars from different disciplines and professions, with an emphasis on British, Irish, American and European houses. The ‘big’ names include Hermione Lee, Margaret Macmillan, David Cannadine, Jenny Uglow, Julian Barnes, and it focuses on 19th century British writers and a peculiarly British form of being ‘the writer’ in a mixture of eccentricity and domesticity. (My review here)

So somehow or other I started off with a castle and ended up in a house.