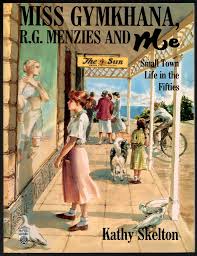

I hadn’t heard of this book, which was sent to our former CAE bookgroup as part of their mop-up operations, now that the CAE no longer runs its bookgroup program. Apparently my group read it about 25 years ago, but I hadn’t joined at that stage. I am the youngest (!!) in the bookgroup, and as the book is about ‘small town life in the Fifties’, my fellow bookgroupers probably recognized even more in the book than I did. But even for me, born in the mid-50s, there was much that was familiar but is lost now, in a world that is much more complex and hurried today.

I guess you’d classify it as a memoir, but it is more a memoir of a time rather than events. The author, Kathy Skelton, was born in 1946 and grew up in Sorrento, a sea-side town that still has its tourist season and its quiet season. It’s a strange place, Sorrento: there have always been very wealthy people there, but also just ‘ordinary’ small town people there as well. In her introduction, she reflects on the nature of memory. Reflecting on famous people that she was aware of at the time- President Nasser, Archbishop Mannix, the voice of Mr Menzies, the young Queen Elizabeth and the Petrovs- she reflects:

Have I printed their images, acquired much later, on a childhood, half grasped and half remembered? Have I overlaid fragments of memory with layers of stories, recounted by others, stories that in turn are their fragments of memory?

I have done all these things, yet still believe I know these events and people intimately, that I have remembered accurately, and that these memories are shared with others who did and did not live in our town. (p.4)

Her book is centred on Sorrento, but she takes a wider view as an observer. She has a child’s-eye view of politics. Her father’s family were Liberal voters: her mother’s family were Labor, and even Communist. The arrest of the Petrovs made an impression on her, although she thought that they looked a lot like Cec and Una Burley, who lived around the corner. Cec was the school bus driver, and Una Burley was the local gossip, and many paragraphs are prefaced with “According to Una Burley….”. Robert Gordon Menzies, the Prime Minister, seemed to be an immovable fixture of the 50s and early 60s, almost beyond politics to the eyes of child (I remember feeling the same way). As with the Queen, political figures were just there, unquestioned. The school turned out to see the Queen, catching the bus into Melbourne to line up along Toorak Road, only to see a “white-gloved hand and a pale face below a thatch of violets” (p. 98). The next Sunday it appeared that the Queen might be coming down to Sorrento to visit prominent resident M. H. Baillieu, but these ended up being put aside because the Royal Couple were resting “their shoes off, stretched out on a spare bed in Government House. Their intended visit was nothing more than a rumour started by persons unknown.” (p. 99)

Likewise, she observes but does not participate in the sectarian split that divided 1950s Australian society, played out at the political level through the ALP/DLP split, and at the personal level through family allegiances to either the Catholic or Protestant churches. As the child of a ‘mixed’ marriage, she attended both the Catholic and Anglican churches. She writes of the Billy Graham crusade at the MCG on 15 March, attended by 130,000 people, 15,000 more than had watched the Melbourne 1956 premiership. She was there: she made her decision for Christ, but “I knew already that I didn’t want to enter into correspondence about God and Jesus and whether I was leading a Christian life, with anyone” (p. 63)

Her description of school life, marching, grammar classes, the march through Australian history of Explorers and Sheep are all familiar to me: obviously school rooms didn’t change much in the 50s and 60s.

Her family was not rich, and her father was a “drinker”. She feared the Continental Hotel (still prominent on the hill in Sorrento) and wished that her father was one of the Men Who Were Not Interested in Drink.

The men who were interested were in the front bar of the Continental every evening, drinking more desperately and rapidly as six o’clock approached. I tried never to go past the Conti after five because of the frightening noise, the hot air, and the beery smoke that might rush out to engulf me as the door opened with men going in and out. But more than the small and the noise, I feared looking up through the golden letters on the window, PUBLIC BAR, into my father’s eyes. (p. 132)

They only had television for two weeks in 1958 when they borrowed another family’s television and kelpie while they were on holidays. They went to the movies, they listened to the radio. They had purchased a refrigerator on hire-purchase, but her father forgot to make the payments and a note was left warning that it would be repossessed unless the money was found. As a result, her mother never bought anything else on hire purchase, and so it took years for the wood stove to give way to the white electric stove, the Hoover to take over from the straw broom, or the wireless to give way to the television.

From her child’s eye viewpoint, she observes her mother’s anger and bitterness towards her father, his family and small town life, but it is somehow separate from her. She sees the young girls who win beauty contests, marry the local footballer, and suddenly are saddled with children and shabby cardigans, all the glamour gone from their lives.

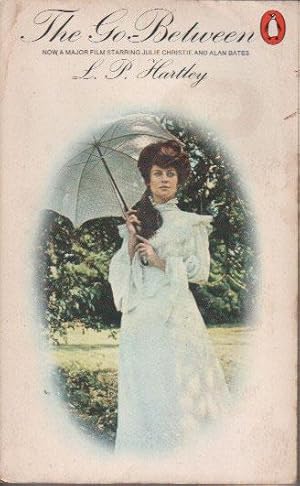

Sex, politics and religion: she sees all these but they are not questioned or challenged. It’s a world that has been congealed in aspic, with certainties and truths, petty triumphs and small luxuries. A very different world. I think that much of the appeal of this book is the nostalgia and sense of safety that it evokes. You can understand why conservatives turn to the past to go ‘back on track’ or making America/ or whatever country you choose ‘great again’. There’s not a lot of analysis, but it’s not completely local either: Skelton has, as she said, evoked memories that are both local to Sorrento, but also common to other Australians at the time. At times I felt as if I were suffocating in mothballs and tight clothes, at other times I yearned for the simplicity and innocence of earlier times. I do wonder how someone born in the 1980s or 1990s would read this book. I suspect that it really would seem, as L.P. Hartley said, like a foreign country, where they do things differently.

My rating: 7/10

Read because: Bookgroup

Sourced from: Left-over CAE book.