Forest 404 (BBC) I don’t know quite how I got onto this, but somehow or other it ended up on my phone. I don’t even quite know what it is: I think that there are stories, (of which this Episode 1 is the first) that are linked to soundscapes and related talks. Anyway, this first episode is set in the 24th century when a librarian, Pan, is charged not with conserving but destroying sound files from the 21st century, which are taking up too much storage space. After the Cataclysm (which waits to be explained), data storage space was recognized as finite, so all the sounds of the past, e.g. a Barak Obama speech, the words when man first walked on the moon etc, are being expunged. Then Pan comes across a recording of a rainforest, and even though she doesn’t know what it is, she finds herself drawn towards it. I don’t know if I’ll persist with this, but the concept of ‘sound’ as artefact is ideal for the podcasting medium.

99% Invisible. Pharmaceutical companies direct their energies towards diseases where they are going to make profits – big profits. This program, Orphan Drugs is actually from November 2018, and it looks at the drugs that pharmaceutical companies decide not to continue manufacturing, even though they may have been life-changing for a small number of people. It tells the story of Abbey Meyers, whose son suffered with Tourette’s Syndrome, who finds herself as an advocate for orphan drugs, trying to lobby government and drug companies to continue to make these no-longer-lucrative drugs available. Of all people who stepped in to help with Jack Klugman and his brother, from Quincy M. E. (remember that?) who used the program to highlight the issue. But, as Abbey Meyers, be careful what you wish for. The resultant Orphan Drugs legislation, which she spent decades lobbying for, has had unintended consequences.

Conversations (ABC) And while we’re on the subject of Big Pharma, the estimable Richard Fidler interviewed Beth Macy, the author of Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors and the Drug Company that Addicted America. In ‘Taking the Pulse of a Dopesick Nation‘, she tells the story of how drugs like oxycontin etc. were falsely marketed as being slow-release and therefore non-addictive, as the memory of the dangers of prescription medicine receded and ‘pain’ began to be seen as a treatable condition in its own right again in the 1990s. The information that came with these prescription drugs warned not to break the coating of the pill, because, as it happened, it was only the coating that made them slow release. Ironically, she sees the only solution in treating addiction as a medical problem and using other drugs as a way of treating the ‘dopesick’ feeling after coming off these drugs, because abstinence and all-or-nothing thinking just doesn’t work. Very interesting and makes you disgusted at the lack of morals of Big Pharma.

Conversations (ABC) And while we’re on the subject of Big Pharma, the estimable Richard Fidler interviewed Beth Macy, the author of Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors and the Drug Company that Addicted America. In ‘Taking the Pulse of a Dopesick Nation‘, she tells the story of how drugs like oxycontin etc. were falsely marketed as being slow-release and therefore non-addictive, as the memory of the dangers of prescription medicine receded and ‘pain’ began to be seen as a treatable condition in its own right again in the 1990s. The information that came with these prescription drugs warned not to break the coating of the pill, because, as it happened, it was only the coating that made them slow release. Ironically, she sees the only solution in treating addiction as a medical problem and using other drugs as a way of treating the ‘dopesick’ feeling after coming off these drugs, because abstinence and all-or-nothing thinking just doesn’t work. Very interesting and makes you disgusted at the lack of morals of Big Pharma.

While I was there at Conversations, I also heard Susan Orleans (who wrote The Orchid Thief) telling the story of the burning of the Los Angeles Central Library in 1986 – something that certain escapes my memory. Did you know that when books are wet, they either need to be dried out within 48 hours or frozen? That’s how thousands of books ended up in meat storage freezing facilities for years. You can hear it at ‘When the Library Burned‘

And although there was nothing particularly new in it, ‘How a milkmaid with cowpox changed history‘ was quite interesting in that it brought together a lot of stories about disease and vaccination.

Background Briefing The Night Parrot is the Holy Grail for bird watchers, and there have been a number of programs on the ABC celebrating the ‘discovery’ of the Night Parrot by bird watcher John Young. But in this program ‘Flight of Fancy: the mysterious case of the Night Parrot’, there are now real questions about the veracity of this ‘find’, and I can only assume that Our ABC did its legals before broadcasting this program, made by Ann Jones from ‘Offtrack’.

The Documentary BBC World Service Well, this was depressing listening from two very different places in the world. ‘Polands Partisan Ghosts‘ is about the adoption by the far right of the ‘Cursed Soldiers’ who were responsible for murder and arson in the time immediately following the Second World War. ‘India’s Forbidden Love‘ is about inter-faith and inter-caste marriages that are running up against the prejudices of the past, fanned by increased religious/national identity. Poland and India couldn’t be more different, but the rise of intolerance cloaked in nationalism right across the world frightens me.

I have included this book on the

I have included this book on the

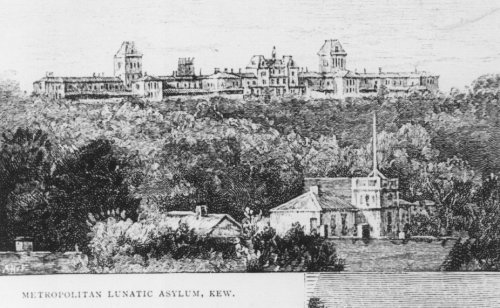

Royal Historical Society of Victoria. After reading Jill Giese’s

Royal Historical Society of Victoria. After reading Jill Giese’s