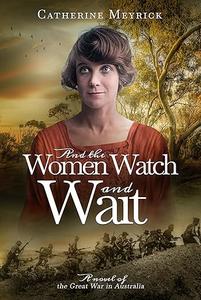

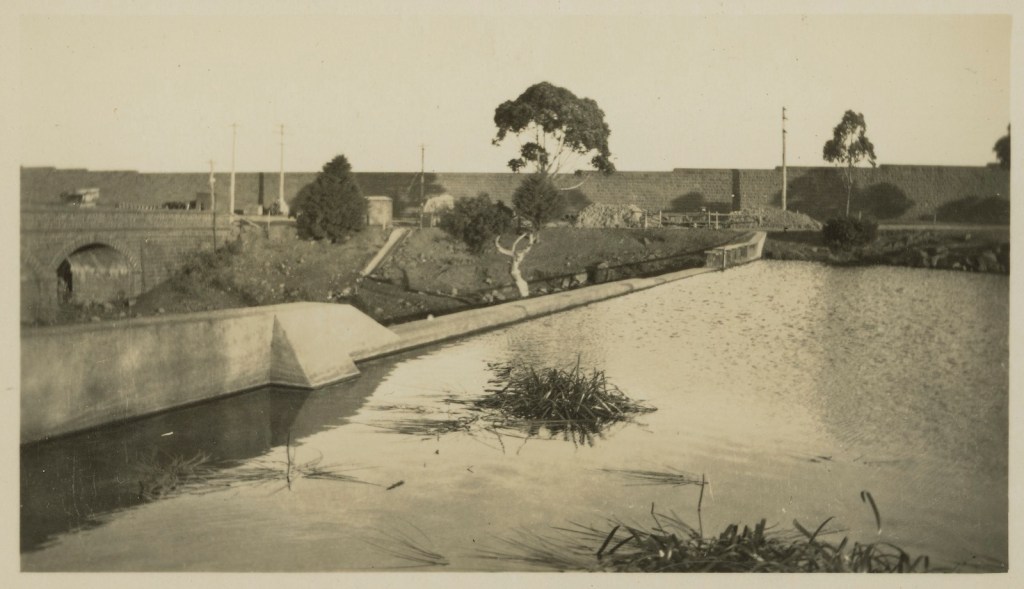

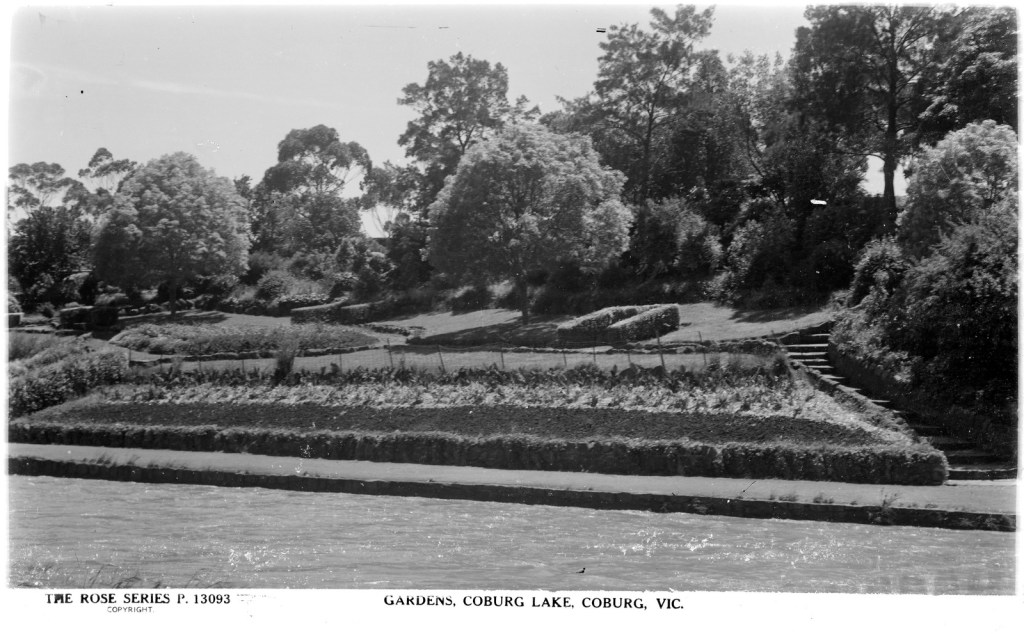

Especially in the wake of the centenary of WWI, there has been no shortage of books about men’s experience in war. They’re usually big fat books, often named for a battleground in large letters, with the (male) author’s name is letters much the same size. Women’s experience- especially the experience of women who didn’t go to war but instead stayed home waiting- is less often documented. And the Women Watch and Wait is based in suburban Coburg in Melbourne, and it captures well the dissonance between suburban life and battlefields far away, the agony of curtailed and delayed communication, and the emotional peril of allowing yourself to fall in love.

Kate is a young country girl who has been sent down to Coburg as company for her Aunt Mary, whose two sons have volunteered and been sent overseas as part of the first contingent of soldiers to be deployed. As well as the excitement of staying in Melbourne, Kate is excited that her boyfriend from Gippsland, Jack, has been sent to the nearby Broadmeadows Training Camp, and there are more opportunities for them to meet up before he leaves than there would have been had she still been in Gippsland. Time is rushing on, as the rumours of the trainees’ departure mount, and she is excited when Jack proposes to her. At this stage, there is still hope that ‘the boys’ will be back by Christmas, and there seems such pressure of time to commit, to get married and start up a married life. Jack leaves with his detachment, and Kate is left with her aunt, working in her aunt’s grocer shop, teetering between excitement to receive mail, and yet fearing what news the mail might bring. News does arrive, and she, along with the women among whom she is living, has to readjust her hopes for the future.

I’m probably a particularly critical audience for this book, because as it happens I’ve been writing a column for the newsletter of my local historical society for the past ten years or so that looks at events at the local Heidelberg level one hundred years previously. Just as Catherine Meyrick would have done in researching this book, I’ve followed the local newspapers closely, consciously looking for women’s experiences, reading every page and even the advertisements and classifieds. This has given me a close-up knowledge of one suburb, (albeit a few suburbs away from Coburg) and how the world-wide events of WWI impacted the social and political life of a community. I must say that she has nailed the local aspects, and I found myself nodding away to parallels that arose in her book which also occurred in Heidelberg.

The book is arranged chronologically by year, starting in 1914 and going through to 1919 with an epilogue. It has over sixty short chapters- too many, I feel- and the frequent changes of location made it feel a little like a screenplay. She integrates political events of the day, like the conscription debates, into her narrative and, again, she captures this big event playing out in small halls and conversations so well. I particularly liked that she explored the WWI experience from the Catholic viewpoint, something that is not represented well in the local newspapers that I have read.

It’s a difficult thing to undertake huge amounts of research, then to let it go in case it smothers the narrative (an advantage that historians have over novelists). At times I felt that small local details were made too explicit, but I’m also conscious that I may have read this book differently to the way that other people might read it. At an emotional level, the book rang true with love, fear, vulnerability and strength being lived out not in trenches but in suburban houses and streetscapes.

My rating: 7/10

Sourced from: purchased e-book. Check https://books2read.com/AndtheWomenWatchandWait/ for availability

Read because: I noticed that the author had linked to several of my posts.