2017, 205 p.

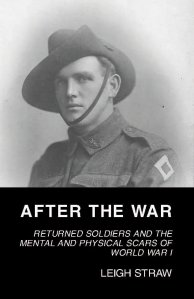

It’s a strong, handsome face that appraises us from the front cover of Leigh Straw’s After the War. When the author saw it from the front page of the muck-racking Truth newspaper, she was struck by its resemblance to her own husband. It accompanied a report of a murder-suicide in Collie in 1929 where an Andrew Straw had murdered Muriel Pope in the street by shooting her, before turning the gun on himself. Leigh Straw, a historian who is better known for work on the Sydney and Melbourne underworld from the 1920s (see one of my reviews here) had stumbled on her own real-life family crime, one that had been suppressed and altered in family lore.

Andrew Straw, returned WWI veteran, is just one of the West Australian men that Straw deals with in this book. There are fifteen main protagonists, with the brief appearances of another fourteen veterans, all of whom volunteered as members of the 1st AIF. Her book takes us through enlistment, fighting, and their return to Western Australia, with a particular focus on the difficulties they faced when returning to their families in a society limping through indifferent economic conditions towards the Depression.

Chapter 1 ‘When the Call was Given: A Nation at War’ summarizes the war experience from enlistment, Gallipoli, the Western Front and the Armistice. Here we meet many of the men who will reappear in later chapters. These are personalized further in Chapter 2 ‘Dad did his turn at the war’: War Experiences’.

Chapter 3 ‘Civilian Life’ brings them back to Western Australia. Arrangements for repatriation had been set in train right from the earliest years of the war, and injured men were being sent home long before the final demobilization at the end of the war. Of the 32000 Western Australian men who had volunteered for the war, 24,000 returned with 16,000 of them injured, invalided or incapacitated by mental or physical wounds.

Soldiers with tuberculosis faced years in and out of sanatoriums as shown in Chapter 4 ‘Isolated: Tubercular Soldiers’. Western Australian soldiers had the added complication that many of them had been miners, or lived in mining towns. At first the Repatriation Department (always keen to reduce ‘shirking’) raised questions about prior mining work and war service. However, most medical reports highlighted the war experience as a causal factor even where there was a work history in the mines. Tuberculosis can sometimes take years to manifest itself, and gradually the policy of restricting payouts for tuberculosis to a two-year period after the war was eased to allow for later illness. The Woolooroo Sanatorium for tuberculosis patients in the general population was established 50 km outside Perth in 1915, just after Gallipoli, and it was expanded after the war with a military section.

Ch 5 ‘Unbalanced’: The ‘Mental Soldiers’ of War’ examines ‘shell-shock’, ‘war neurosis’ and what we would now call PTSD. As Marina Larsson points out in her book Shattered Anzacs (my review here), families fought hard to have shell shock distinguished from ‘mental illness’ more generally. They advocated for separate facilities at Stromness Hospital and Kalamunda Convalescent Home to distinguish returned soldiers from the patients at Claremont Hospital for the Insane, but there was always cross-over between the two.

In Chapter 6 ”A Ruined Man’:Postwar suicide’, Straw turns to the newspapers to find details of this outcome of war that was so difficult to talk about by immediate families. West Australian government policy shamefully decreed the destruction of inquest reports after ten years, and so she needed to turn to newspaper reports when the inquest notes did not appear in the repatriation files. Using Trove, she sampled between 1915 and 1940, after which point World War II reports made searching by keyword more difficult. She found that veteran suicides accounted for more than 10 percent of all registered male suicide deaths in the state- a number which was lower than I expected. However, as she points out, deaths reported as ‘accidental’ or through drowning allowed widows or family members to claim a war pension, when a finding of suicide did not. Those that were reported as suicide generally (60%) involved fatal gunshot wounds, most to the head or chest. Almost one third involved poisoning. One distinguishing feature from the current-day veteran suicide statistics was the number of self-inflicted razor wounds. Nearly 40% of the suicides took place in the five years between 1925-1929, before the Great Depression, but when a large number of men reached middle age and struggled to find work. War pensions were increasingly questioned and lowered from 1925. Alcoholism featured heavily, and there were marital and family problems.

Chapter 7 ‘War’s Aftermath: Family stories’ turns to the oral histories given by family members, both to Leigh Straw herself and to earlier oral historians. For a number of these families, including Straw’s own, these stories went untold for years . ‘Conclusion: the men who came home’ summarizes the findings of the book, and a final epilogue ‘A Disordered Brain’ returns to Andrew Straw’s story – the man whose face is on the front cover, and who was the impetus for this book.

This book, written in 2017, locates itself and pays tribute to much of the work on war injury, repatriation and the effects on family which has been undertaken over recent years. There is much of it, and I found myself wondering why Straw chose to move out of her academic field of crime/social history of the early-mid 20th century when so many other historians have worked in the area of WWI repatriation before her. I’m thinking, for example, of Marina Larsson, Joy Damousi, Stephen Garton and Alistair Thomson – all of whom have written about loss and return over the past twenty-five years.

I think that part of the answer lies in the event that prompted to her to write: the discovery of a close family relationship, that even travelled generations to manifest itself in the face of her own husband. Other books on the same topic tell individuals’ stories and use oral histories, as she has done. But in this book, she focusses on fifteen men whose stories re-appear across the various chapters of analysis, supplemented by other examples. It is an academic history, complete with footnotes and literature review, written with a family history focus.

A second aspect is its emphasis on Western Australia, rather than the more populous eastern seaboard. In this regard, it is no surprise that the book was published by University of Western Australia Publishing. Western Australia’s commitment to the war effort was the highest in the country by proportion of population, with close to 10% of the state’s population enlisted in the war. The state more strongly supported conscription than the other states, right throughout the war. Many of the enlistees from WA were relatively recent arrivals from Britain or Victoria attracted perhaps by the 1890s gold discoveries, with possibly shallower family connections. Schemes and plans for repatriation were implemented across the nation, but being so far distant from the other states, the Western Australian government worked largely in isolation.

This is an easy book to read, despite its difficult themes. It is an academic text, but with its grounding in the lived experience of men and their families, it wears theory and argument lightly. Beyond the photo of Andrew Straw on the front cover, it does not have any pictures, which is surprising given the co-operation the author received from many family members. But perhaps that is not the drawback it might appear. Photographs, with their staging and smiles, do not capture the pain and struggle that is perhaps more apparent taken across the whole life span, and into further generations. That comes from stories, and this book is replete with them.

My rating: 7/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

After the War was joint winner of the 2018 Margaret Medcalf Award from the State Records Office of Western Australia.

I have included this on the database of the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2020

I have included this on the database of the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2020

I have included this on the database of the

I have included this on the database of the  I’m absolutely delighted that

I’m absolutely delighted that