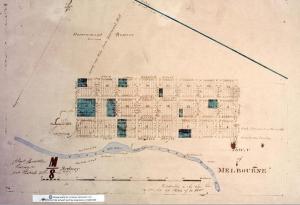

Judges may write poetry all the time- how would I know?- but I suspect that it’s not a particularly common judicial past-time. William a’Beckett, the fourth Resident Judge of Port Phillip did, though, and this small book surveys his literary output from the early 1820s through to the early 1860s when he had retired back in England. Forty years…so much poetry…such awful poetry. Well maybe not, if you like rhyming poetry because certainly Sir William did. But these poems were of their time and fashion and should be read that way.

The author, Clifford Pannam QC starts his book with a reflection on the portrait of Sir William that hangs on the walls of the first floor of the Supreme Court library. Although a’Beckett’s writings have been dismissed as “sentimental, priggish and rather boring”, Pannam decided to plunge into Sir William’s extra-judicial writings and found that:

[Sir William’s] literary works reveal a romantic and passionate man who found no embarrassment at all in public confessions of his innermost feelings. (p. 4)

The first chapter deals with a travel book that Sir William wrote in 1854 on a 4000 mile European journey that he undertook with his wife and sons between August and November of 1853. It’s a fairly conventional travel diary although he is moved to poetry in Naples. In a poem ‘At Naples- 1853’ he looks back to a poem that he was inspired to write there more than twenty years ago as a young man and compares his life then and now. It’s quite biographical in places, especially when he writes about the death of his first wife.

In Chapter Two, Pannam moves to Sir William’s distress at his son’s marriage to Emma Mills, the brewery owner’s daughter. Most of this short chapter deals with how this event was fictionalized in the works of Sir William’s great-grandson, Martin Boyd, about his family (The Cardboard Crown and The Montforts).

Chapter Three tracks back to Sir William’s publication of his verse under the title ‘The Siege of Dumbarton Castle and Other Poems’, published in 1824. Between 1824 and his call to the Bar in 1829, Sir William had had hundreds of poems published in literary periodicals, and in 1829 he published them in a 200 page book ‘The Vision of Noureddin and Other Poems’ under the pen name Sforza. There are long extracts of poems…such ‘rhym-y’ poems. He also wrote a three volume biography of eminent people, where in the introduction Sir William admits that it was copied from other sources over four years. Pannam notes that “It is difficult to imagine a more crushingly boring task for a young man.” (p.38) This was, however, a common way of compiling text books for young barristers waiting around for briefs.

Chapter Four sees Sir William now in New South Wales in 1838 where he delivered a series of three lectures at the Sydney Mechanic’s School of Arts entitled ‘Lectures on the Poets and Poetry of Great Britain’. Extracts appeared in the Temperance Advocate (he was a strong Temperance supporter) and he published the lectures separately, the first work of literary criticism published in Australia. He gave a similar lecture series at the Melbourne Mechanics Institute in 1856. I must confess, reading them through, that they’re not exactly riveting reading and were probably even less riveting listening.

Chapter Five has assorted poems on varied topics: Christmas; his first wife; the conformity of the Anglican church; prize fighting; and the damaging effects of creeds- something that as a Unitarian he would have felt strongly about.

The sixth chapter examines a pamphlet that Sir William wrote under the pen name ‘Colonus’ titled “Does the Discovery of Gold in Victoria, viewed in relation to its Moral and Social Effects, as hitherto developed, deserved to be considered a Natural Blessing or a National Curse?” As you can guess, by the length of the title, he came down pretty much on the latter.

He did do some professional writing as well, and Chapter Seven looks at the 100 page book that Sir William wrote in 1856: ‘The Magistrate’s Manual for the colony of Victoria’ (the title is longer, but you get the gist). But he also wrote current-events poems that he submitted to the Port Phillip newspapers (especially the Port Phillip Herald) under the pen-name Malwyn. Pannam reproduces ‘Leichardt’s Grave’, written after the explorer Ludwig Leichardt disappeared the first time then re-appeared (less lucky the second time he disappeared….)

In Chapter 8 Sir William retired and returned to England in 1857 and published a “very long and marvelously romantic poem” under the title ‘The Earl’s Choice’ in 1863. It’s an apt description for this overwrought work, and at least he’s broken out of the straitjacket of rhyme.

Finally, in Chapter 9 Pannam leaves us with a poem on the future of Victoria “Advance Victoria!” also found in ‘The Earl’s Choice’ which you can download free as a Googlebook here.

Advance, Victoria!

From crowded cities severed far

Where glitters bright the southern star

There lies a land of wide domains,

Of golden rocks, and grassy plains;

Whose soil to till, and wealth unlock,

From distant climes, all people flock,

Whilst, canopied ‘neath cloudless skies,

They help a mighty nation’s rise.

If you have access to AustLit, his works are listed there. If you’re a member of the State Library, you can view it online.