1999, 163 p & notes

It really wouldn’t have surprised me if this book had been reissued in the last five years, but it wasn’t. It would have done very well in the deluge of books about WWI between 2014 and 2018, and dealing as it does with loss experienced during and resulting from World Wars, it fits very neatly into the ‘history of the emotions’ school of historical enquiry, which has high prominence at the moment. But it wasn’t reprinted, and so it remains a fore-runner to much work that has been completed in its wake.

As Damousi says in her introduction

This book examines the stories of those for whom loss in war remained the experience through which they understood themselves, and through which they shaped their lives. After the wars ended, their lives had been irrevocably changed through continuing grief, for the burden of memory would remain with them as they attempted to rebuild an internal and external world without those to whom they had been so fundamentally attached. (p. 6)

Damousi is very conscious that she is dealing with ‘white’ soldiers and the experiences of their families, and mentions in several places that the burden of memory was often disregarded for indigenous soldiers. A strong gender theme runs through her analysis.

The book is divided into two parts. The first deals with the First World War, the second part deals with the Second World War.

Part I : The First World War

1. Theatres of Grief, Theatres of Loss

2. The Sacrificial Mother

3. A Fathers Loss

4. The War Widow and the Cost of Memory

5. Returned Limbless Soldiers: Identity through Loss

Part II The Second World War

6. Absence as Loss on the Homefront and the Battlefront

7. Grieving Mothers

8. A War Widow’s Mourning.

Conclusion

The themes of the grieving mother and wife are dealt with in both sections, while other themes e.g. soldiers writing to bereaved families, the return of limbless soldiers, or absence from home are dealt with in one section only. I’m not sure that there is a qualitative difference between these emotions and events between the two world wars, and perhaps the decision to locate a topic in one war rather than the other depended on the sources that Damousi uses.

As Damousi points out in Chapter 1, when a soldier died at the front, it was quite common for his friends in the battalion to write to his grieving family themselves. Sometimes bereaved families ‘at home’ drew their son’s friends to themselves like adopted sons. While writing these letters to other families at home, the soldiers were almost rehearsing their own possible death. Meanwhile, back on the homefront, delayed letters continued to arrive from sons who had been killed , and bereaved families forged their own links with each other.

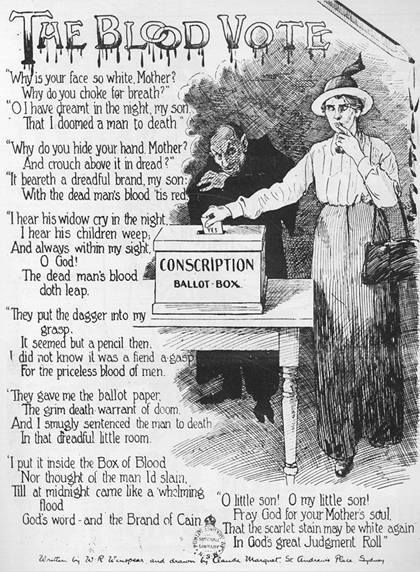

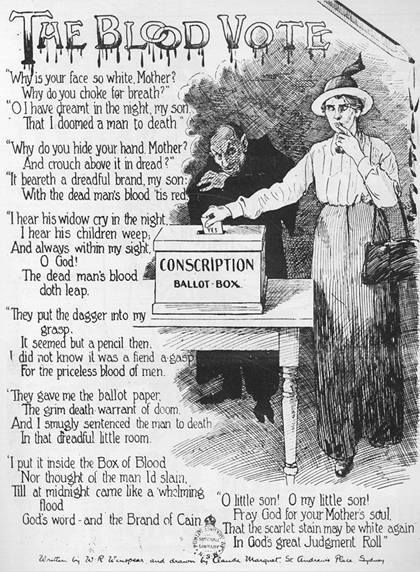

Wikimedia

Chapter 2 and Chapter 7 both deal with grieving mothers, but in World War I the mother figure had a political as well as familial role. Not only was the mother lauded for “giving up her son” but the Conscription debates drew heavily on the image of the mother both as the one who sacrificed, but also the one who determined, men’s fates. ‘The Blood Vote’, for instance, placed the burden of decision onto mothers, rather than fathers or sisters.

Yet when it came to financial support for widowed mothers who lost their sole breadwinner, mothers soon found the limits to compassion for their sacrifice. After being giving a prominent role in the immediate post-WWI period, by the 1930s mothers found themselves shunted to the side of parades and their pensions became increasingly inadequate over time, especially when additional payments were granted to widows but not mothers.

In the World War II section on mothers, Damousi makes similar observations, drawing on the diary of Una Falkiner, whose son died in a plane accident in September 1942, and Hedwige Williams whose son Charles Rowland Williams died in Germany in May 1943. This chapter -, shaped perhaps by the sources available? – seemed to me to have a deeper emotional timbre than the corresponding WWI chapter.

Chapters 4 and 8 deal with war widows. What is common to the experience in both wars was that the war widow tended to become public property as her lifestyle and life choices were judged by others to determine whether she qualified for a widow’s pension. It became rather unedifying as neighbours, other widows and mothers informed on those who they felt were ‘undeserving’. Again, in relation to the Second World War section, the same themes recur in the experience of women in the two wars, but in Damousi’s account she draws more heavily on a particular source – in this case, Jessie Vasey, the widow of General George Vasey who died in an Australian plane crash when he and several other high-ranking defence officers died near Cairns. She channelled her grief into political and charitable action for war widows but, once again, after the immediate post-war years, women found themselves and their sacrifices pushed aside.

The correspondence between the Vaseys also features strongly in Chapter 6 ‘Absence as Loss’ where Damousi draws on Vasey’s letters back home to illustrate the yearning for domesticity expressed in much wartime correspondence. Interestingly, I have just finished listening to an excellent podcast series called Letters of Love in World War II, where a British couple range over philosophy, yearning and domestic trivia in their 1000-letter correspondence. Again, it is perhaps not so much a qualitative difference between the two wars, as a question of sources.

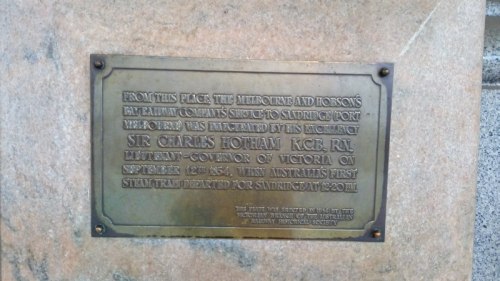

The depth of sources has possibly also influenced Damousi’s decision to deal with fathers’ grief in World War I, and not in World War II. In Chapter 3, ‘A Father’s Loss’ she examines the extensive archive of John Roberts, an accountant with the Melbourne Tramways Board, who lost his son Frank on 1 September 1918 at Mont St Quentin. Perhaps there was a particular plangency in losing a son so close to the Armistice; or perhaps the almost-obsessive pursuit of every possible way of documenting and making contact with those who may have seen, or been with, his now-departed son reflected Roberts’ own personal approach to traumatic events. In either case, Roberts’ correspondence is a rich and complex archive of grief for the historian. More generally, however, fathers maintained a more prominent public part than mothers and widows in commemorating their sons through political organizations and they leveraged their ability to influence policies. In the Second World War, however, fathers (many of whom had served themselves in World War I) found that the reactivation of war challenged their ideas of patriotism and their own earlier sacrifice. They often found themselves harking back to their lost pre-WWI world, which they had been unable to secure.

Of course, World War I and World War II was interspersed by the experience of the Depression. It forced hard decisions about sacrifice and worth in finding and holding scarce employment. As Damousi points out in Chapter 5, initially there was strong pressure for governments, councils and private employees to offer jobs to returned WWI soldiers, and particularly soldiers who had been injured. However, when jobs became scarce, returned men without injuries were preferred employees, and war widows were expected to yield their jobs to returned soldiers.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the title of this book. I’m not sure if the loss that she mentions here involves “labour” as such, although it certainly was a life-changing event for those who were left. But then I find myself thinking of the title of Shakespeare’s play “Love’s Labour Lost” which to me has its echoes in this title. For, without actually spelling it out in her title, what comes through in Damousi’s examination of memory and grief, is “love”.

I have included this on the Australian Womens Writers Challenge database for 2019.

I have included this on the Australian Womens Writers Challenge database for 2019.

Source: La Trobe University Library

Nothing on TV I’ve just started listening to Robyn Annear’s podcast series ‘Nothing on TV’. It’s great. Annear is a Victorian historian, whose book Bearbrass largely sparked my interest in Melbourne, and she is wry, funny, and quirky. As is this podcast. She draws on the marvellous resources of the online Trove database to chase down odd events, and researches them further. In

Nothing on TV I’ve just started listening to Robyn Annear’s podcast series ‘Nothing on TV’. It’s great. Annear is a Victorian historian, whose book Bearbrass largely sparked my interest in Melbourne, and she is wry, funny, and quirky. As is this podcast. She draws on the marvellous resources of the online Trove database to chase down odd events, and researches them further. In