Perhaps biographies are like buses….nothing for ages, and then two or three arrive all at once. Vida Goldstein, the subject of this 2020 biography by Jacqueline Kent, did not receive a full-length biography until 1993, when Janette Bomford published her book That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman: Vida Goldstein, which I reviewed here. She featured in Claire Wright’s You Daughters of Freedom in 2018, and appears as a minor character in Caroline Rasmussen’s recent joint biography of Maurice and Doris Blackburn The Blackburns (2019). She has always appeared as part of the network surrounding Stella (Miles) Frankin and Catherine Helen Spence, but in terms of full length biographical treatment, the two main works have appeared in the last 27 years.

In her introduction to this biography, Jacqueline Kent notes that Goldstein is briefly mentioned in almost every history of women in Australia, but “her name is not particularly well known outside scholarly circles”. (Voters in the federal seat of Goldstein, in the bayside areas of Melbourne might beg to differ. As Kent points out, the electoral division might be named after her, but it has never sent a female MP to the House of Representatives). Kent writes that her biography

…seeks to show how much Vida was not simply a woman of her times, but someone whose views and beliefs are refreshingly contemporary – and so who is equally a woman of our time.

(p.xv)

Kent has written other biographies, but she is best known for her biography of Australia’s first female Prime Minister, Julia Gillard The Making of Julia Gillard (2009) and a smaller work Take Your Best Shot: The Prime Ministership of Julia Gillard (2013). Gillard remains a touchstone throughout this biography of Vida Goldstein as well, with Kent inserting present-day comments drawing parallels between Goldstein and Gillard’s experiences in parentheses in various places throughout the text. This connection comes to the fore in the epilogue, where Kent claims that Vida and her colleagues would have been “delighted to see Julia Gillard confirmed as the country’s first woman prime minister” which she follows with a four-page summary of Gillard’s prime ministership. This presentism is foreshadowed in the subtitle ” A woman for our time”.

When writing her biography, Janette Bomford bemoaned the lack of a cache of personal papers that would reveal the inner Vida Goldstein. Kent has had to work from the same straitened resources, and a quick glance at the footnotes reveals Kent’s debt to Bomford’s earlier biography. As a result, I’m not going to reprise Goldstein’s life here – instead I refer you to my review of Bomford’s book – because the events are much the same, which is to be expected when both authors are working from the same sources. Kent briefly raises, but then shuts down, speculation that Goldstein may have had a lesbian relationship with her friend and colleague Cecilia John. I’m not sure that it is a useful suggestion as there is absolutely no evidence for it, but perhaps it was prompted by Kent’s attempt to frame Vida as “a woman for our time”.

So where, then, does the difference lie in the two biographies? Unfortunately, I must have borrowed Bomford’s book because I can’t find it on my shelves, so I don’t have the two texts on my desk to compare. I can only work from impressions.

First, Kent’s book seems more Melbourne-oriented than I remember Bomford’s book being. Although she travelled to both U.S. and U.K, and although she had connections with feminists in other states, Goldstein lived and worked at the Victorian level in trying to get female representation in Parliament. Although given importance in the text and forming stepping stones in her life’s chronology, these national and international personal networks do not play an integral part in Kent’s narrative. Instead, Goldstein comes over as rather isolated and toiling away single-handedly here in Victoria, estranged both from party politics (which she abhorred) and by her conflicts with other feminist groups and political forces.

Kent gives us a good picture of Victorian political and intellectual life in the first twenty five years of the twentieth century. Paradoxically, Victoria was the last state to grant female suffrage in 1911, and the right to stand for State Parliament in 1923, even though white women had been able to vote in federal elections and stand for Federal Parliament since 1902. Although the first suffrage society in Australia was the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society in 1884, and despite Victoria’s relatively progressive intellectual life, the Legislative Council was able to stymie women’s suffrage and representation long after South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales had granted it. As a result, Goldstein’s many attempts to stand for Parliament involved federal elections, not state ones.

However, her main base of support was in Victoria, centred on the Book Lovers Library, run by her sister and brother-in-law in the city, and Oxford Chambers at 473-481 Bourke Street which for a while, became “something of a Goldstein compound” where the family members lived and worked. Her two newspapers, the Australian Woman’s Sphere (1900) and the later The Woman Voter (1909) were published in Melbourne.

Second, Kent gives full weight to Goldstein’s spiritual commitment, first to Rev Charles Strong’s Australian Church and then to First Church of Christ, Scientist, which was to remain her lodestar throughout her life. It was a commitment that caused tension with her friend Stella (Miles) Franklin, and it became increasingly important to Goldstein in her later life as a conscious choice in career direction. Perhaps it’s because I too am a Woman of a Certain Age, but I’m increasingly interested in how biographers deal with the latter years of their subject’s life. Kent handles this well, tracing through Goldstein’s contributions to public debate long after she had given up on unsuccessfully standing for Parliament.

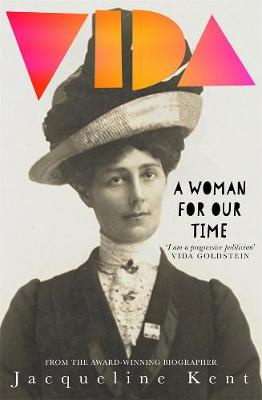

Third, Kent’s biography has a lightness of touch that was less evident in Bomford’s more academic book. This is partly because of the parenthesized present-day asides, but also because Kent has a good eye for the visual image and the lively event. I’m not sure, though, that she has moved our understanding of Goldstein forward by much beyond what Bomford had already told us. But through the striking cover, the title with its present-day hook and the engaging writing style, Kent has probably broadened awareness of Vida Goldstein to a wider audience.

My rating: 7.5- maybe 8/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

I have included this on the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2020.