If you’ve been following my blog for a while, you’ll know that I’m rather uncomfortable with the current trend to write history as a quest, interweaving the researcher/narrator’s perspective on the search with the actual history itself. Initially, I loved it as something brave and humanizing. But after at least a decade, it’s becoming a bit tired, and I feel that it is often resorted to as a symptom of the paucity of sources, as much as anything else. Ah, but I’ve said this again and again, and now I’m even boring myself.

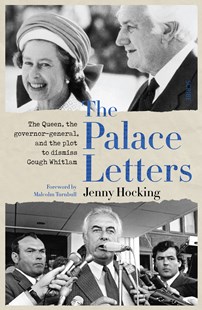

But sometimes the historian genuinely is part of the history, and this is certainly the case in The Palace Letters. Jenny Hocking has written a two-volume biography of Gough Whitlam, and has been working on the Dismissal for many years. Indeed, if it were not for her persistence, and the generosity of pro-bono legal representation, historians would only have been able to work with retrospective accounts of the leadup to the 1975 dismissal of the Whitlam government. The real-time documentation leading up to the November 11 1975 events was held at the pleasure of the Queen as ‘personal’ documents instead of the Commonwealth records that they are. After the National Archives refused Hocking access to the correspondence between Sir John Kerr and the Queen’s Private Secretary Sir Martin Charteris after the statutory period had elapsed, she embarked on a ten-year battle to resolve the status and ownership of these documents as part of the historiographical record of Australia. This book is the story of that fight.

I have been following her battle for several years , especially through her recent book The Dismissal Dossier and I think I even threw some money towards her crowd-funding campaign to fund her legal expenses. After the papers were finally released, I can remember feeling somewhat disappointed that there was no ‘smoking gun’ of a Palace conspiracy, but rather the self-serving and pompous bleatings of Sir John Kerr, the Governor-General who did not cover himself with glory in November 1975 or in the years afterwards. But having read, The Palace Letters there is, at the personal level on the part of the Queen’s Private Secretary Charteris, a passive encouragement to Kerr, and certainly a structural effort to keep this communication hidden on the part of the National Archives, Liberal/Coalition governments over the decades and the Palace itself.

The book is written in the first person, with remarkably little self-promotion and puffery on Hocking’s behalf, even though she could have easily trumpeted her credentials for writing this book. It starts off in the archives, where all historians love to be, and her discovery that there were actually two copies of the letters: the first, the actual letters and the second, a photocopy made at night by David Smith, the Governor-General’s official secretary in order to send to Kerr to write his Journal. When both copies were placed under an embargo by the Palace on the grounds that they were personal papers, she thought that she would never see them. It was when she read Sydney barrister Tom Brennan’s blogpost ‘Australia owns its history‘ that she realized that there were legal allies with whom she could join forces.

The book then moves to the various court cases that the issue moved through, and the arguments that were made on both sides for or against the release of the letters. She was a participant, rather than a disinterested observer, and the National Archives does not come out well, in her retelling, taking advantage of tactics like unequal access to information, obfuscation and courtroom time-hogging. Headed by David Fricker, a former deputy director-general of ASIO, it becomes clear that the Archives are more than just a repository for documents but a political actor in their own right. There is even a National Archives whistle-blower who, infuriatingly, conveys important information at such a late stage that it cannot be used. The Murdoch-owned Australian is a player here too, and it is not surprising that Australian journalists Paul Kelly and Troy Bramson have published The Truth of the Palace Letters as a counter to Hocking’s analysis of the letters, once they had been made available.

Hocking gives a good sense of the imbalance of this fight: the National Archives are able to draw on their government-provided budget (albeit at the expense of their other activities) whereas Hocking could be held personally responsible for court costs. Although she was able to negotiate a capping of these costs, and was able to draw on the cream of Australia’s legal system for pro-bono representation, there must have been many times when she felt sick to her stomach at the implications of the losses in court. For losses there were, and it was only when it went to the High Court and received a 6:1 victory, that the long battle had been vindicated.

The final third of the book looks at the content of the letters themselves, and the aftermath of the Dismissal for Kerr himself as the Palace distanced itself from both Kerr and the decision. At one stage Sir Martin Charteris referred Kerr to a book written by conservative Canadian politician and expert on the reserve powers of the Crown in former dominions, Eugene Forsey, which enlarges the scope of the question beyond just Whitlam and Kerr into a broader historical question. However, after the dismissal, the time for book recommendations had passed, and Charteris becomes frostier, with Kerr’s actions now in the past.

While, of course, tales of the archives and courtroom stories will appeal to a particular type of reader, this book itself is very accessible. Who said that historians can’t be heroes? If you’re tempted to read it, read Hocking’s The Dismissal Dossier first (which will probably get you fired up) and then read this book, almost as a type of morality tale, to see the Mighty Fallen and the rewards for persistence and the courage to put yourself on the line – for our right to know our own history.

My rating: difficult to rate…8?

Sourced from: e-book from Yarra Plenty Regional Library.

Interesting article: https://auspublaw.org/2020/08/the-constitutional-historiography-of-the-palace-letters/

I have included this on the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2021.

I have included this on the

I have included this on the