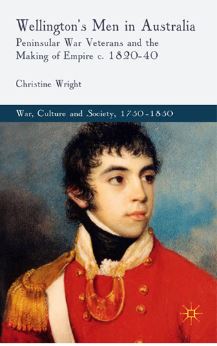

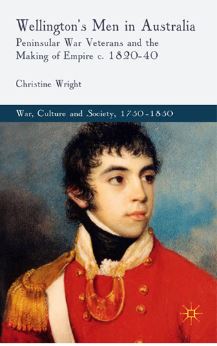

Wellington’s Men in Australia: Peninsular War Veterans and the Making of Empire c1820-1840 by Christine Wright

2011, 178 p and appendices

I often found myself closing the book while I was reading it to look closely at the striking image on the front. It’s a miniature of James Thomas Morisset (1780-1852), painted when he was about eighteen years old. Those who loved him must have later regarded it with wistful sorrow, because he was shockingly disfigured at the battle of Albuera in 1811 as part of Wellington’s Peninsular campaign at the age of 21. He is such a beautifully formed boy, and not at all like the description that the second in command, Foster Fyans, gave of his commandant on Norfolk Island some thirty-odd years later:

The Commandant, a gruff old gentleman with a strange face, on one side considerably longer than the other, with a stationary eye as if sealed on his forehead; his mouth was large, running diagonal to his eye, filled with a mass of useless bones; I liked the old gentleman, he was friendly and affable, and thought time might wear off his face affliction, which was most revolting: the one side I could only compare to a large yellow over-ripe melon ( Fyans, ‘Memoirs Recorded at Geelong’ cited on p. 169)

Morisset is one of the men that Christine Wright deals with in her prosopographical study of men who served during Wellington’s Peninsular campaigns on the Iberian peninsular from 1808 to 1814. Prosopography was defined by the historian Lawrence Stone in a foundational article as “the investigation of the common background characteristics of a group of actors in history by means of a collective study of their lives”. As such, it falls half-way between rather sketchy biography and a more statistical analysis. I’ve read several legal prosopographies, and one or two about bureaucrats: it seems to be used mainly in the context of writing about careers (although it could just as easily be applied to any group of people). It is well suited to Christine Wright’s endeavour. When reading local histories sited in the British colonies during the 1820s, 30s and 40’s you come across ex-military figures again and again, and in this book Wright takes this cohort of soldiers, bonded by their experience in the Peninsular campaigns, and traces the rest of their careers throughout the empire.

During the Napoleonic Wars the need for manpower rendered the old system of purchasing of commissions inadequate. Young soldiers of limited means, who would not normally have had the capital to purchase their positions not only had a career pathway open up for them during the war, but also were eligible for half-pay and land grants after the war. As veterans, they were able to draw on the networks of influence to gain positions across an empire which was calling out for their skills in logistics, engineering and surveying. The half-pay entitlement was insufficient to live on in Britain which drove veterans to look for employment overseas, and from the British Government’s point of view it was a way of cutting the cost of numbers on the half-pay list while filling appointments with skilled men and their families.

In the colonies, veterans in garrison regiments and ex-soldiers who had sold their commissions fitted particularly well into the military structures of early NSW and Van Diemen’s land. As the colonies evolved away from penal settlements to free colonies, these ex-military men were well placed to take up civil positions of power and authority in the community. They obtained large grants of land complete with convict labour and accrued the status that accompanied being a landowner- something that they probably never would have been able to achieve in Britain.

But the army had given them more than just military skills. The drawing and surveying skills developed during the war were put to use in colonies that were still exploring their spaces. Beyond their practical uses, these skills flowed into art as well, where ex-veteran painters, alert to the stark light and harshness of the Spanish terrain, were able to capture the light of Australian landscape in a way not seen amongst painters who had spent all their lives in the soft lights of England or wooded European settings. Accustomed to making written reports, many of the veterans wrote their memoirs of the Peninsular campaign but extended their memoirs into their new settings as well.

Veterans were often deployed on the frontier in various roles: explorers, magistrates, Mounted Police, Border Police and as military commandants of penal stations. The term ‘frontier’ means different things to different groups: there were different frontiers depending on whether you are talking about ‘big man’ sheep farms, ‘small man’ cattle farms and agricultural mixed farming. Some historians prefer the term ‘contact zone’ rather than ‘frontier’. Missionaries saw it as the advancement of civilization. In military terms, though, the frontier was

a strategic boundary, a defensive line, and the front line of colonial order. The military saw it as the shifting boundary of British civilisation that had to be defended. (p. 152)

On this basis, Wright gives an insightful re-reading of the Waterloo Creek massacre from a strictly military viewpoint. The British Army ceased fighting on the frontier in the latter half of 1838 and it was left to the settlers or to Border or Mounted Police which, although joined by many ex-soldiers, were not counted as part of the British Army regiment numbers. She suggests that this changed the nature of frontier ‘clashes’ and not necessarily for the better.

The real grunt-work of this book comes in the appendices which lists influential British Army Officers in the Australian colonies who were veterans of the Peninsular War. They are listed by name, regiment, date and place of arrival, place of death, with a brief summary of the military and civil positions they occupied in Australia. There’s many familiar names there: several governors (George Gawler in South Australia; Governors Darling, Brisbane, Gipps, Bourke, in NSW), explorers (Sturt, Major Mitchell, Lockyer), commissariats (Logan up in Moreton Bay, G.T.W.B Boyes in NSW and VDL) and commandants (Thomas Bunbury, Joseph Childs, poor damaged James Morissett in Norfolk Island), surveyors (Light in South Australia, and many magistrates and crown land commissioners (Fyans).

The chapters are arranged thematically, each headed by a quote:

- ’emigration is a matter of necessity’: The aftermath of the Peninsular War

- ‘they make Ancestry’: Veterans as Officers and Gentlemen

- ‘we are in sight of each other’: The Social Networks of Veterans

- ‘attached to the Protestant succession’: The Religious Influence of Veterans

- ‘an art which owes its perfection to War’: Skills of Veterans

- ‘with all the authority of Eastern despots’: Veterans as Men of Authority

- ‘in the midst of the Goths’: The Artistic, Literary and Cultural Legacy of Veterans

- ‘to pave the way for the free settler’: British Soldiers on the Frontier.

The book emerges out of the author’s PhD and I think that it is still detectable there. At times the language was a little stilted and the author’s interventions rather forced. I was mystified by the capitalization (or lack thereof) of certain names, especially the Duke/duke of Wellington.

The reader meets many of these veterans in several chapters in different guises. The backgrounding for individual characters comes in various places. For example, Archibald Innes’ background story comes at p. 44; G.T.W. Boyes’ comes at p. 132 even though they have been mentioned briefly in many other places. While spreading her net wide, there is no one place where she introduces key figures as, for example, Inga Clendinnen did in Dancing with Strangers. I found myself wondering if perhaps this might not have been a better strategy: I found myself more interested in characters once I’d been formally introduced to them. Certainly the ‘networked’ aspect comes through clearly as people are appointed to one position after another, often through the sticky web of the Darling/Dumaresque connections in Sydney, or through the good graces of Secretary of State for the Colonies Sir George Murray in London, himself a Peninsular veteran.

It is telling that the book takes such a short timespan (twenty years) as its period of analysis. By 1840 the militarized nature of Australian society had been overlaid by move towards civil appointments, bureaucratic rather than martial procedures and even representative government.

As often happens, once you’ve been alerted to a phenomenon, you tend to see it everywhere, and this is the case with this book. If you flip through the entries for early settlers in the Australian Dictionary of Biography you’ll see the military connections with new eyes and wonder why it wasn’t more apparent before.

I am posting this for the Australian Women Writer’s Challenge under the History/Biography/Memoir section. It is an academic text, and needs to be read that way.

I am posting this for the Australian Women Writer’s Challenge under the History/Biography/Memoir section. It is an academic text, and needs to be read that way.