There’s a fantastic exhibition on display at Bundoora Homestead called “Coming Home” that commemorates the use of the homestead as a convalescent farm and repatriation mental hospital between 1920 and 1993. Even though it’s ostensibly an exhibition about the use of a house, it’s a sad and very human exhibition. There are none of the brass bands and official ceremonies that we saw last week at Albany , but this exhibition is an act of commemoration nonetheless.

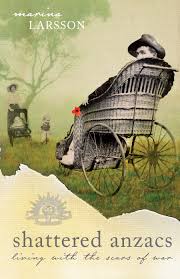

As I’ve written about previously, (here and here) Bundoora Homestead was built in 1899 by the Smith racing family as their residence and stud farm. In 1920, immediately in the wake of WWI the Commonwealth government negotiated the purchase of Bundoora Park estate as a convalescent farm for returned soldiers from the WWI front. As Marina Larsson wrote in her book, Shattered Anzacs (review), the families of returned servicemen with mental illness were keen that their loved ones not been seen as ordinary ‘lunatics’, but housed and treated in repatriation facilities in recognition of their war service. Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital was sited across the road from Mont Park as a separate, soldiers-only hospital that could draw on the facilities of the civilian asylum nearby.

The exhibition focuses on individual men, most particularly Wilfred Collinson and Harry ‘Lofty’ Cannon, who spent decades of their lives at Bundoora.

Wilfred Collinson was a British migrant, who arrived in Australian in 1914. He hadn’t been here long, working as a farm labourer with a friend that he’d met on the ship over, before the two lads volunteered and were returned to Europe to fight in WWI. He had a long war, and was gassed four times. On his return to Australia he and his friend, Eric Brymer, boarded in South Melbourne, and Wilfred soon married the girl next door and embarked on a family life. His children grew up with a father affected by “nerves” who became increasingly delusional, and eventually he was committed to Bundoora in the 1930s. As Larsson points out, families often had to battle the government for pensions and recognition that illnesses and injuries were war-based, and Wilfred Collinson’s wife is a case in point. His friend Eric Brymer, who was the only person who could testify to what Wilfred had been like before the war, wrote a letter in support of his wife’s application on her husband’s behalf. Then followed another thirty-five years, and two generations, as his wife and daughter, then daughter and his granddaughter, went out to visit ‘Dad’ at Bundoora. He died there in 1972. His war, in effect, was never over. (You can see the video of his daughter and granddaughter on the exhibition site here. The video is also running at the exhibition).

Harry ‘Lofty’ Cannon was a medical orderly with the 2/9 Field Ambulance and Changi POW. We’ve all heard about Weary Dunlop, but I’d not heard of Lofty Cannon. He was a tall man- 6 foot six- but it was a shrunken life that he returned to after WWII. He’d married just six days before leaving for the front, he fought in the Malay campaign and was captured as a prisoner of war in 1942. While he was at Changi he met Ronald Searle, an English prisoner-of-war, who later credited Lofty with saving his life, nursing him through beri-beri and malaria. Lofty wasn’t in much better shape, with ulcers, malaria and dysentery and the after-effects of beatings from the Japanese guards. He was hospitalized at the Repat. in Heidelberg in 1946 on his return to Australia, where he received ECT and insulin coma therapy. By 1947 he and his wife were living on a soldier-settlement farm near Swan Hill but by 1960 his wife and adopted son returned to Melbourne and Lofty went to Bundoora. From Bundoora he wrote letters to his wartime friend, Ronald Searle in England, by now a noted artist and illustrator, probably best known for his St Trinian’s illustrations. Much of the display shows Searle’s sketches that he made of Changi, several featuring Lofty. These are in the possession of the State Library of Victoria, and you can see them online if you search slv.vic.gov.au for “Cannon, Harry (Lofty)”. He died in 1980 at Bundoora. Rachael Buchanan wrote a terrific essay about him in Griffith Review 2007 freely available here.

Bundoora Homestead is beautifully restored and such a peaceful place today that it’s hard to believe that so much sadness seeped through its walls and the now-demolished wards that once surrounded it.

The exhibition runs until 7 December at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, 7-27 Snake Gully Drive Bundoora, Wed-Friday 11.00-4.00 p.m and Sat and Sun 12.00-5 p.m.

Website: http://www.bundoorahomestead.com/