Axios – How it Happened More Ukraine. Putins Invasion III: How It Could End. In part three, Axios World editor Dave Lawler examines a difficult reality — that the only clear path to peace in Ukraine is a deal between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, but the red lines drawn by the Russian and Ukrainian leaders do not intersect. This episode features interviews with Zelensky’s chief of staff, a member of Parliament in his party, two close observers of Putin and the Kremlin, and a former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine with decades of diplomatic experience in the region. The interviewees point out that Zelensky is very ideological, a good listener, but that you can’t pressure him. They point out that legally, Ukraine’s borders can only be altered via referendum (and the Ukranian people are not likely to vote for that). Putin cannot win, but Zelensky will not accept Putin’s terms. Putin’s best hope is to exhaust Ukraine and the interest of the west. Something, they all agree, will have to change.

History of Rome Podcast Episode 121 Phase Three Complete sees the mop-up before Diocletian comes on the scene. Mike Duncan starts off this episode, reflecting that people who were born during the Severin epoch had only know the chaos of the 3rd century when emperors came and went in regular succession. They didn’t realize that they were just about to turn the corner. We don’t really know much about Carus and his two sons Carinus and Numerian. Carus was about 60 years old, and he had been a Praetorian Prefect. Realizing that he couldn’t spread himself across the empire, he sent his son Carinus to Rome and he headed to Persia to fight the Sassanids with his other son, Numerian. It was a good time to attack Persia because the Persians had just committed most of their troops to invading Afghanistan. Carus died: struck by lightning, they said, as a punishment for straying too far outside of the empire. His son Numerian, spooked perhaps by this theory, withdrew back to the borders, even though they were beating the Persians. His sons had a brief reign until Diocles came on the scene. Apparently he was a real back-room operator. There had been a prophesy that Diocles would only become emperor when he killed a boar, and this came true when he executed the Praetorian Prefect Aper for murdering Carus’ son Numerian. ‘Aper’ means ‘wild boar’, although historians dispute this story as being ridiculous. But hey- lots of things here are ridiculous. Diocles changed his name to the more regal-sounding Diocletian and began bad-mouthing Carinus. He was about to battle Carinus, but Carinus (conveniently) died. Episode 122 Jupiter and Hercules As a back-room political operator, Diocletian had actually thought about the empire, instead of having it thrust upon him. He decided that there would be no Senatorial purges, but he also decided that he would side-line the Senate altogether. He decided that there had to be two Emperors, so he appointed Maximian to rule over the West as co-emperor with Diocletian who would rule the East. Maximian was a soldier, and so not a political threat to Diocletian. However General Carausius, who had been appointed in charge of operations against pirates on the Saxon coast, went rogue, proclaimed himself Augustus and set himself up in Britain. Diocletian came across to the West to bolster Maximian’s troops. To boost their authority, Maximian also took up the title of Augustus, and then Diocletian appealed to the heavens for legitimacy (much as Augustus had done), thus laying the foundation for Divine Right for the next 1500 years. He claimed that he had been appointed by Jupiter himself, and Diocletian assumed the title Iovius, and Maximian assumed the title Herculius.

The History Hour (BBC) usually has a couple of stories on different topics but in this episode Ukranian History Special, they concentrate on events in Ukraine’s history. It is really good. It starts with the explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in April 1986 and the tardiness of the government response. It moves on to the Budapest agreement where the international community – including both Russia and the USA – offered security “assurances” to Ukraine in return for giving up its share of the Soviet nuclear arsenal. Then there is a survivor’s account of Ukraine’s great famine in the 1930s, the Holodomor, when several million people died (although she was very young- about 3. I’m not too sure about the fidelity of the memories of a three year old). It moves to the mass killing of Ukrainian Jews by Nazi Germany during World War Two- noting the irony that Putin has used ‘anti-Nazi’ as a justification for invasion. Finally, in an abrupt change of pace, the episode finishes with how Artek, on the shores of the Black Sea in Crimea, became the Soviet Union’s most popular holiday camp. Really worth listening to.

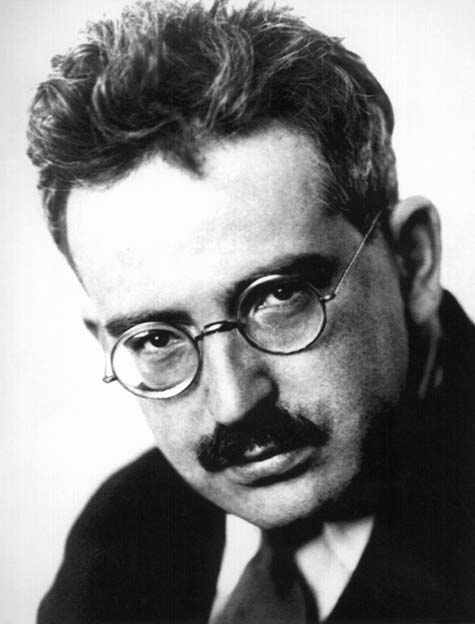

In Our Time (BBC). I thought that In Our Time must have finished, because I couldn’t find it on Stitcher but then I discovered that you can access it through BBC Sounds. Old Melvyn Bragg is sounding older and more slurred. I’ve never read any Walter Benjamin (and in fact, for half the podcast I had him mixed up with Isaiah Berlin). He was an academic, but he styled himself as a critic of what was then the modern media. Born in Germany, from the late 1920s he led a mobile life living in Russia, Italy and France. He was not interested in writing about the past as it was, but seeing it in terms of the questions of the present. Notably, in his Arcades Project, he looked into the past of Paris to understand the modern age and, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, examined how the new media of film and photography enabled art to be politicised, and politics to become a form of art. As a German Jew, he was fearful of the rise of Hitler and was interned in Paris and although, because of his eminence he had an entry visa to America, but he could not get an exit visit. Although in very poor health, he decided to walk from France to Spain but, in very poor health and realizing he wouldn’t make it, he committed suicide on the way. Most of his work was published posthumously and taken up by the 1960s counter culture. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction greatly influenced John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, and is even more apposite given the rise of digital cameras everywhere in galleries and museums and NFTs.

History of Ideas- Talking Politics. I started listening to this ages ago and just stumbled over it again on my ‘Favourites’ list. David Runciman, a professor of politics at Cambridge (and not, as I thought, the Archbishop of Canterbury) goes through the major political works starting with Hobbes. I listened to Hobbes and Wollstonecraft but then skipped a few because I was interested in Marx and Engels on Revolution. This was the best description of Marx and Engels’ ideas that I’ve heard. He points out that where Hobbes saw revolution as the problem, Marx and Engels saw it as the solution. The ideas of revolution in The Communist Manifesto were not taken up at all in 1848 (although they wrote it in a hurry because they hoped that they would be), and their ideas in their death throes during WWI when it turned out that the workers of the world did not unite but instead fought each other. However the Russian Revolution in 1917 vindicated them, and the fortunes of the book have waxed and waned ever since. They point out that the state will always be in crisis, and that in replacing the people who run the state, there will inevitably be violence. Revolution has to be international, and that has not happened (and in current events, is not likely to do so). Runciman considers that the most successful revolutions were in East Germany and Eastern Europe in 1989 and the 90s. He points out that both 1848 and the Arab Spring were short term failures, but they did have an impact on democracy later (I think that the Arab Spring has yet to show results). He questions whether class today is as important as Marx and Engels thought, suggesting that education level (albeit related to class) and age (youth) are more important on voting patterns.

Things Fell Apart (BBC) This is a terrific series about the culture wars, and things that make you scream at the television. One Thousand Dolls is about the beginning of the culture wars over abortion in America. Until the 1970s, anti-abortion was a Roman Catholic thing, but Frank Schaeffer, the son of an influential Christian art historian, talked his father into adding an anti-abortion segment into his art history films. Although poorly received, he decided to make a highly emotive Christian film against abortion, and it came to influence many anti-abortions including James Kopp, who murdered Barnett Slepian, an American physician from Amherst, New York who performed abortions. He has since distanced himself from the anti-abortion movement. Really interesting.