As we get older, we approach the ‘senior’ category that covers adults from 60-100, a forty-year age range. It would be unthinkable to conflate, say, a 10 year old and a 50 year old, but somehow after 60 all ‘old people’ are lumped in together. I wouldn’t be the first person, I’d wager, to regret that there were conversations that I didn’t have with my parents as a ‘senior’ myself, and questions that I didn’t ask about their earlier lives..

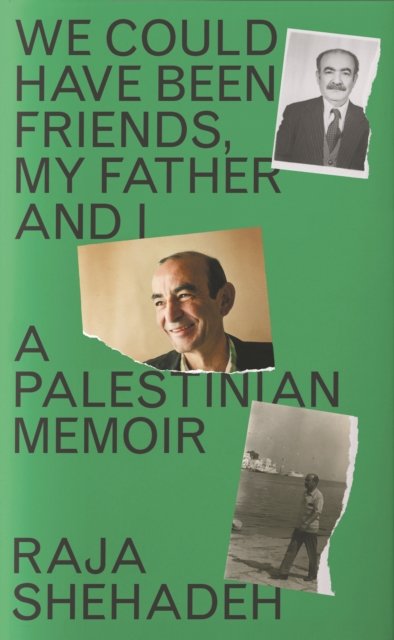

Palestinian Human rights lawyer and author Raja Shehadeh has even more regrets. When his 73-year-old father was assassinated outside his own home by a disaffected litigant in 1985, Raja was 34 years old and working in his father’s law firm. The murderer was a squatter on land belonging to the Anglican Church, and his father was handling the case for his eviction. The Israeli police closed the case, assuring the family that they were doing everything they could to find the murderer, but they knew who the murderer was and did not want to charge him. (p. 13) After his mother nagged him into going and collecting his father’s papers, Raja ended up with a cabinet of papers, which he stored on the bookshelf. He opened them, and found everything meticulously arranged, but felt overwhelmed by it all. The last case they worked together on involved plans for roads to be constructed throughout the West Bank. His father directed him to the documents he should consult, but showed only moderate enthusiasm for the case, which he left mainly in his son’s hands. Still smarting from this rejection, for many years he viewed the documents as nothing more than “a source of years of hardship and trouble”. (p. 17)

It was only when a friend brought him a photocopy of the Palestinian telephone directory for Jaffa-Tel Aviv dated January 1944, a city to which his father could not return after 1948, that his father’s long history of activism became real to him.

When I began reading, I realised with what impressive clarity my father had set forth his thoughts, and how his pioneering ideas were deliberately distorted by Israel, the Arab states and even some Palestinians. For so long his written attempts at setting the record straight had met with failure. I felt guilty that all these years had passed before I could spare the time to study the files in the cabinet and finally do what I had failed to do during his life: understand and appreciate his life’s work. (p. 17)

This book, then, is the story that was revealed through those documents. It is a history of the years immediately surrounding the Nakba. It illustrates the perfidy of Great Britain and Jordan in the establishment of Israel, the intransigence of the PLO and the whole generational cycle of Palestinian history that existed before the author’s birth. His father and other Palestinians at the time, rejected the creation of UNRWA (which is currently in the news now because Israel wants to outlaw it) because it made the Palestinian cause one of humanitarian response rather than justice.

His father took up the cause of Palestinian savings, which were frozen by the banks leaving Palestinian refugees unable to exchange their Palestinian pounds into pounds sterling or any other Arab currency. In February 1949 the Israeli government ordered that Barclays Bank in Britain and the Ottoman Bank formally transfer all ‘frozen’ Palestinian funds to the Custodian of Absentee Property, which after a while proceeded to liquidate the assets as if they belonged to the State. His father mounted a legal challenge against Barclays Bank at the District Court in Jerusalem, which was part of Jordan at the time. He won.

He decided to run as a candidate in the Jordanian parliament, but found himself arrested instead. He proposed the establishment of a Palestinian state next to Israel along the 1947 partition borders, with its capital in the Arab section of Jerusalem. This put him at odds with the PLO, which wanted a secular democratic state over the whole of Palestine, not a Palestinian state alongside Israel. His father was clear-eyed about Israel’s deceptions over various peace initiatives, and always believed that it was preferable for the Palestinians themselves negotiate with Israel, rather than have Arab states negotiate on their behalf ( as occurred during the Trump-inspired Abraham Accords, and is still occurring over any possible ceasefire in Gaza).

Too late, there was so much that the Raja of today could have discussed with his father, had he lived. It’s revealing that, despite their shared interests and objectives, the emotional tenor of the father/son relationship overpowered their intellectual one. He was intimidated by his father and he resented his dependence on him in the office.

For years I lived as a son whose world was ruled by a fundamentally benevolent father with whom I was temporarily fighting. I was sure that we were moving, always moving, towards the ultimate happy family and that one day we would all live in harmony. When he died before this could happen, I had to wake up from my fantasy, had to face the godlessness of my world and the fact that it is time-bound. There was not enough time for the rebellion and the dream. The rebellion had consumed all the available time. I turned around to ask my stage manager when the second act would start and found that there was none. I was alone. There was no second act and no stage manager. What hadn’t happened in the first act would never happen. Life moves in real time. (p. 12)

The language in this book is a little stilted, but any adult child can feel this same remorse for lost opportunities, and the jolt of being alone on the stage, once one’s parents have died. This book gave me a good sense of the generational injustice that is still being fought out in Gaza and the West Bank today, and the pettiness and duplicity of many of the main actors. Colonialism up-close, and without the patina of centennial celebrations and ‘age-old’ traditions is an ugly, ugly thing.

My rating: 8/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

Sounds like a very good read especially for those of us who are focusing on our foibles in the parent child relationship rather than drinking up the blessed time we have with our loved ones.

Pingback: ‘The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine’ by Rashid Khalidi | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip