I confess that I started this book warily. “Mad as a Meat Axe” write two daughters on their mother’s medical chart at the end of the bed, sniggering at the thought that the initials MMA might prompt some medical profession to treat their mother for MMA and kill her. The two daughters, who are never named, are visiting their mother in rehab for a broken hip, even though their mother denies their existence, and has had nothing to do with them for eighteen years. I would not want these daughters.

Obviously much has gone on in this family, but we are never told. Our narrator tells us that, for her:

My past is not merely faded, or camouflaged under the dust of years. It’s not there, and I know a blessing in disguise when I see one. I have managed to shake free and flee to far-flung places where I feel reasonably safe because I do not carry a lot of my past. (p.140)

And yet, after 18 years, this Canadian academic returns home to see her father, whom her mother has announced “doesn’t have long”, and her mother whose hip has disintegrated. Along with her sister, who has remained in Canada despite the 18 long years of estrangement from her parents, they arrange (conspire?) for their mother to be moved into some form of care, so that their father can escape from her clutches. Her mother has long since given power of attorney to someone else, and she announces that her daughters are only after her money. Are they? Who is mad as a meat axe here?

It took a while for me to shake my suspicion of the narrator. I wonder if this book is some sort of Rorschach test: I have been the child left (albeit in a completely different situation) and so perhaps I read it differently. As older sister, the narrator has fled to Australia and established a marriage and career there, while her younger sister, just by virtue of being in Canada, carries the memories, the hurt and responsibility. The narrator knows this, but this does not change her actions:

…However different we are and however badly she judges me, whatever gulf already separates us, she is my sister. I do not want the gulf to fill with the seething resentment she will feel because she is doing it all, but I know this will happen. I am telling her that I know this will happen. I know she will feel violent annoyance with me when I suggest something because I’m not there and I don’t know, and I’m not the one doing it and I, on my far away island continent, will sit quietly, gnawed by guilt. (p. 157)

We never learn what has happened in this marriage and family. We have little back-story for her parents, beyond the fact that her father made money through the oil industry and that he fought in WWII. We have no images of a courtship, a marriage or a family life with young children. Everything is refracted through the narrator’s rage- which oddly enough, she deflects onto her sister.

No, I see rage here. A rage expressed by staying on the other side of the world, and by allowing her younger sister to carry this burden. A justified rage, from the snippets that we received, but rage nonetheless, despite protestations of guilt.

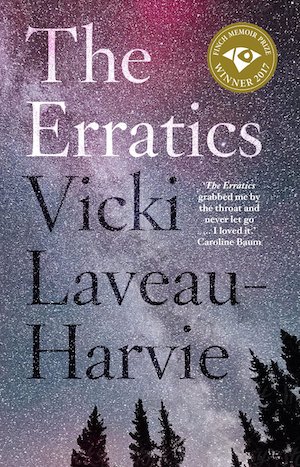

This is a memoir, and as such the author has ultimate freedom and responsibility to shape the narrative however she wishes. The memoir starts with a preface, describing the Erratics, huge boulders deposited by the Cordilleran Ice Sheet as it moved through Alberta and Montana. The Erratic that sits in the Canadian town of Okotoks, where the memoir is set, has cracked and fallen in on itself, posing danger to anyone approaching it. On the final pages, we revisit this image of the Okotoks Erratic with the spirit of her mother sitting atop it, beside Napi the Trickster.

To be honest, I’m still not sure who the Erratic is here: mother or daughter. But either way, it feels as if there is some sort of space here for release.

My rating: 8/10

Sourced from: purchased e-book