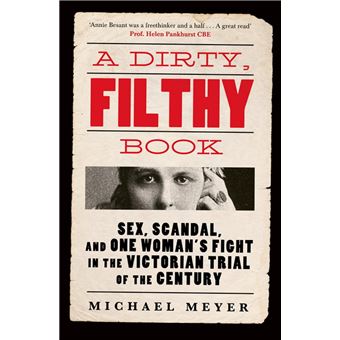

Some people seem to live not just one life, but many. Annie Besant was one such woman who went from parson’s wife, to public speaker and publisher, social worker and activist, to university student and Theosophist. Michael Meyer’s book, subtitled ‘Sex, Scandal and One Woman’s Fight in the Victorian Trial of the Century’ focuses particularly on the court case in which she and her colleague Charles Bradlaugh were charged with “unlawfully wickedly knowing wilfully and designedly” printing and publishing “a certain indecent lewd filthy bawdy and obscene book called Fruits of Philosophy” which would bring the subjects of Queen Victoria into “a state of wickedness lewdness debauchery and immorality”, as well as offending against the peace and dignity of the Queen. (p. 140)

Neither of the accused had actually written the book, which was quite an old text written forty years earlier by an American doctor, Charles Knowlton. In fact, Charles Bradlaugh didn’t think much of the book at all, but it was more the principle of making knowledge available at a cheap price (sixpence) that drove Annie and Charles to defend publishing the book in court. They wanted a high profile case, and they got it. Conducted in Westminster Hall (before it burnt down), it was a jury trial held before the Lord Chief Justice Sir Alexander Cockburn. Already an accomplished public speaker, albeit completely untrained in the law, Annie conducted her own defence, and from the extracts published in the newspapers in this widely-discussed trial, she did a damned good job of it too.

She, even more than her co-accused Charles Bradlaugh, had a lot to lose. She had married a clergyman, Rev. Frank Besant at the age of 18, without actually loving her husband but hoping, as a devout Christian, that the role of minister’s wife would be a way through which she could serve the Church and her fellow man. It was an unhappy marriage from the start. She had two children, a son Digby and daughter Mabel, and managed, through her brother, to procure a separation from her husband but he kept custody of her son, and refused a divorce. If found guilty, Annie would lose custody of her daughter as well.

She had lost her faith during her marriage, and after her separation became heavily involved in the National Secularist Society, where she met Charles Bradlaugh. They were very close, although Meyer does not explore whether their relationship was sexual or not. Both were still married, and as public figures, could not expose themselves to scandal. She wrote numerous articles for the National Reformer weekly newspaper published by the NSS and was an accomplished public speaker. It was this experience of debate and public discourse that stood her in good stead in the courtroom at Westminster Hall, but did not shelter her from the fallout of the case. Charles Bradlaugh went on to have a successful political career, being repeatedly re-elected and repeatedly refused being able to take his seat in Parliament because, as a secularist and atheist, he refused to swear on the Bible. As their lives split off in different directions, the obloquy of her atheism prevented her from being able to graduate from the University of London, once they accepted female students, even though she was clearly a brilliant student. She threw herself into social activism in the East End, particularly in leading the Match Girls strike about working conditions and the use of white phosphorous in making lucifer matches at Bryant and May. Over her life, she had been a devout Christian, a strident atheist, and eventually she moved into Theosophy, to which she devoted the latter part of her life. She abjured her earlier publications, and especially the book about birth control methods that she wrote after the court case which was even more explicit than Fruits of Philosophy. It really is as if she had several careers.

In the book, there are parallels drawn between Besant and two other women. The first of these is circus performer Zazel (Rossa Richter) who drew fame for being shot out of cannon, night after night. The second is Queen Victoria herself, who had a much happier experience of married life than Annie Besant did, and whose politics were diametrically opposed. Queen Victoria was not particularly aware of Besant, but she did record her disapproval of Bradlaugh in her diaries.

When I first started reading this book, I enjoyed its breezy tone and discursive narrative but I soon tired of it. In trying to contextualize Besant and her various campaigns, he draws on newspapers to illustrate what else was occurring at the time, and in the end it became a distracting lack of attention- as if he couldn’t bear to let a juicy tidbit pass, without reporting it. I enjoyed his reporting of the court case itself, but the lack of discipline elsewhere in the book detracted from his analysis of the case and its aftermath. Like the court case itself, it all felt a bit tabloid.

The author is a travel writer, which did not surprise me. He is also Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh, which did.

Nonetheless, it’s a really interesting story and, despite his digressions, Meyer tells it in an engaging and entertaining style. I just wish that there had been a little less ‘colour’ and more analysis.

My rating: 7.5/10

Read because: I heard a podcast about the book

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

Pingback: Six degrees of separation: From ‘Long Island’ to… | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip