It has never really occurred to me to question whether Jesus actually existed. There are many things that I doubt about him- miracles, resurrection, second coming for a start- but his actual existence, no. In fact, having spent a lot of the last three years or so catching up on the history of Rome that I missed out at school and university, it seems to me that the sparse references to Jesus himself and the response of Roman authorities to this small apocalyptic sect are just as you would imagine them to be.

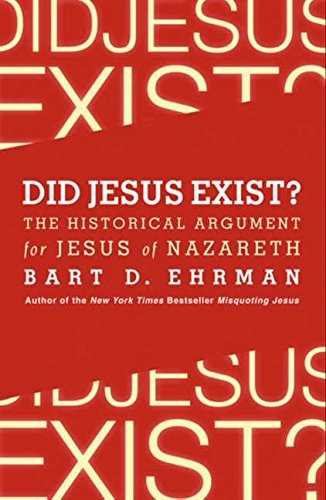

However, as this book makes clear, there is a body of thought (albeit small) that asserts that Jesus never existed at all and was instead a myth that conflated Jesus with existing fertility gods and sun gods. According to this view, no textual evidence of Jesus emerged during the 1st century, having dispensed with the Jewish historian Josephus as a forgery. In his introduction Ehrman namechecks the major current proponents of these views: Earl Doherty, Robert Price, Frank Zindler, Thomas L. Thompson and George A Wells. While acknowledging that several of these authors have academic qualifications in classics and the Hebrew bible, according to Ehrman only one of these- Robert Price- has the intellectual chops in New Testament studies to be a serious contender. Ehrman then launches into his own rebuttal to the ‘mythicist’ position by looking at non-Christian sources for the life of Jesus, the Gospels themselves as historical sources, and other Christian writings that did not make it into the biblical canon. He presents what he considers two key arguments for Jesus’ existence: first, Paul of Tarsus’ personal association with Jesus’ followers and brothers especially Peter and James; and second, the common knowledge that Jesus had been crucified. The crucifixion was an affront to any perception of Jesus as a ‘messiah’, not unlike us finding out that David Koresh at Waco was really the Messiah. He then moves to dismantling the mythicists’ claims through either weak or irrelevant argument, and grappling with the ‘pagan myth’ hypothesis for Jesus’ non-existence. In the last two chapters of the book he spells out his own view of the historical Jesus as a 1st century apocalyptic Jewish preacher- a view that I largely subscribe to as well.

Looking at the list of ‘mythicists’ that he is taking on, one thing stands out to me: they are all men. I rarely mentally link the words ‘testosterone’ and ‘biblical studies’, but the first part of the book reminded me of chest-bumping, shirt-fronting, put-up-your-dukes academic skirmishing. The argument, carefully laid out with centred headings and subheadings felt to me like an extended exercise in man-splaining, complete with the repetition and put-downs. All rather unedifying, I thought.

However, I enjoyed the last two chapters of the book, where he stopped attacking and began presenting his own considered and backed-up views of the historical Jesus. Here is where he and I concur:

The fact is, however, that Jesus was not a person of the twenty-first century who spoke the language of contemporary Christian America (or England or Germany or anywhere else). Jesus was inescapably and ineluctably a Jew living in first-century Palestine. He was not like us, and if we make him like us we transform the historical Jesus into a creature that we have invented for ourselves and for our own purposes…When we create him anew we no longer have the Jesus of history, but the Jesus of our own imagination, a monstrous invention created to serve our own purposes. But Jesus is not so easily moved and changed. He is powerfully resistant. He remains always in his own time. As Jesus fads come and go, as new Jesuses come to be invented and then pass away, as newer Jesuses come to take the place of the old, the real, historical Jesus continues to exist, back there in the past, the apocalyptic prophet who expected that a cataclysmic break would occur within his generation when God would destroy the forces of evil, bring in his kingdom, and install Jesus himself on the throne. This is the historical Jesus. And he is obviously too far historical for modern tastes.

Conclusion

My rating: 7/10

Sourced from: purchased e-book

Read because: in preparation for my now completed talk at Melbourne Unitarian Universalist Fellowship.