2017, 298 p. & notes

This book is exactly what the title promises: a study of Helen Garner and her work. It’s not, and nor does it purport to be, a full biography but is instead a ‘literary portrait’, firmly based on and in Garner’s own writings and writing practices.

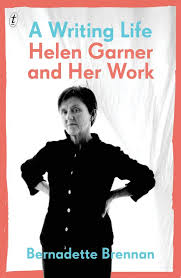

The author (who, judging from her picture on the back page is much younger than I thought she would be) uses the publication sequence of Garner’s books as its organizing principle, but it seems in both the introduction and conclusion that she at one stage contemplated a different structure.

It is too simple to say that Garner’s body of work is one book, but everything she has written is interrelated. Over a period of forty years she has revisited themes, relationships, situations, characters and questions. Because houses, and their domestic spaces of intimacy and negotiation sit at the core of all Garner’s fiction, I originally thought to structure this study around Garner’s primary spaces: bedrooms, kitchens, courtrooms and public institutions… Such readings, however, do not lend themselves to a full and coherent appreciation of Garner’s development as a writer…. In the end I decided to structure this portrait so that each chapter, dedicated primarily to literary analysis, can be read as a room describing Garner’s house of writing. Some rooms have alcoves, others debouch into wider spaces; all are connected by passageways. (p. 7)

I must confess that I forgot about this intended motif until the author returned to it in the closing pages of the book, where she alludes to Henry James’ metaphor of the house of fiction, and Garner as a ‘watcher’ through windows. I don’t find it a particularly useful structure, and as it would seem, neither did the author, as it is left largely untouched through most of the text.

Instead, the book is presented in two parts: Part 1 Letters to Axel and Part II Questions of Judgment. ‘Axel’ was Axel Clarke, the son of historian Manning and linguist Dymphna Clark and a close friend from university days to whom Garner wrote often and honestly. His archive of letters to and from Garner, deposited in the National Library of Australia are a significant resource for Brennan. He died in 1990, after a long friendship with Garner tinged with tension over her ‘use’ of his illness with a brain tumour in ‘Recording Angel’, one of the stories in Cosmo Cosmolino (1992), the last of the works analysed in Part I. The ‘letters to Axel’ form a useful organizing device, although ‘1942-1992’ or ‘The First Fifty Years’ would have done just as well. Each of the seven chapters focuses on a major work and Brennan interweaves personal details, gleaned from Garner’s own works and interviews, and literary analysis based on the books themselves.

Part II, Questions of Judgment starts with The First Stone, the first non-fiction book that took Garner into the courtroom as the basis for her narrative, a practice that she has followed in Joe Cinque’s Consolation, This House of Grief and most recently in her Monthly essay ‘Why She Broke‘. The chapter on The First Stone is the longest in the book and it marks not only Garner’s shift into long-form non-fiction writing, but also her most contentious book that provoked questions among her critics about her commitment to feminism and how that feminism was defined, and her attitude towards younger women. Readers who do not like Garner’s work often criticize her insertion of herself into both her fictional and non-fictional writing, and Brennan (among others) is critical of Garner’s personal intervention in the form of letters to Master Alan Gregory, the man accused of sexual harassment. I had not realized the legal tightrope that her publishers trod with this book, and it took its toll on her relationship with Hilary McPhee. It is a book that still evokes controversy. Most of the books in this second part are non-fiction, which is the genre in which Garner has predominantly worked in the last decades. The exception is The Spare Room, which is the novelized retelling of a real life experience when a friend undergoing an alternative treatment for cancer stayed with her. Brennan’s book closes with Everywhere I Look, Garner’s recent collection of essays.

It is not necessary to have read Garner’s books to enjoy this literary portrait, but it certainly helps to have done so. Critiques of short story and essay collections are always difficult to write and read because the act of describing them often eviscerates them, and several of Garner’s publications fall into this genre. Nonetheless, Brennan gives enough of the flavour of Garner’s works to jog the memory or provide sufficient background for her analysis to make sense.

It is not an authorized biography as such, in that Garner had veto power over it. She made available to Brennan her diaries, letters and drafts that are currently embargoed at the NLA, and participated in interviews with the author. It’s a rich, textured archive.

This is not a biography, and yet we do learn about Helen Garner those things she chooses to reveal about herself, either through interviews or mostly through her own writing. We read about her difficult relationship with her father, her life in share-house Carlton that prompted Monkey Grip, her three marriages, her daughter and grandchildren. There are things we do not learn, too, most particularly who the ‘Philip’ character who floats through her early fictional writing was based on. I did not realize the persistence of Garner’s religious quest, thinking that she had left it behind after Cosmo Cosmolino (which I reviewed here and did not enjoy). I remember, but did not fully appreciate, the virulence of the debate about The First Stone and was unaware of the legal and literary maneuvering that preceded its publication. In my review of Postcards from Surfers, I wondered about how a book of short stories was put together, and in Brennan’s book I saw the collaboration between editor and author in constructing a ‘work’ of short stories as a distinct entity. Through her diaries it is clear that the naive, ‘I-know-nothing-about-the-legal-system-but…’ stance that comes through in her courtroom non-fiction is a deliberate, and somewhat disingenuous choice.

Most of all, though, I am left with a sense of the writer at work– and work it surely is. The reading, the thinking, the writing and rewriting, rewriting, rewriting. The author’s drawing together of observations from other writers and thinkers – most particularly that scholar of the art of biography, Janet Malcolm. The richness and texture of thought and reflection. The edginess and vulnerability of putting yourself out there as an author. The web of connections between people in the local intellectual and literary scene. A life lived in the mind, but also in the everyday. A particular way of looking. All the things that I appreciate most in Garner’s work.

My rating: 8.5

Source: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

I have posted this review at the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2017.

Sounds wonderful. It’s only in the last two or three years that I have seen Garner as anything other than the author of Monkey Grip, which evoked my own early 20s, living in the inner suburbs (though I still haven’t swum at Fitzroy baths). My one question is does Brennan think that Garner tells the truth about herself in her writing?

Ah, I enjoyed your review too Janine. There are so many ways to talk about it. I usually do talk about structure but wanted to focus on other things so left that alone this time around.

I do remember some of the legal stuff about The first stone – specifically the dividing of Jenna Mead into multiple people – because I read quite a bit about the book at the time, but I had forgotten about it until I read Brennan’s book. I thought her chapters on the three big non-fiction works were fascinating. I’m glad you mentioned the point about the “I” being not quite as naive as she pretends to be – but it works I think because it enables us to come along and because it reflects the “I” she would have been had she not been writing the book and done the extra research.

As for Bill’s question, I’d say yes and know. I think the “real” Garner does come through her books, but it depends a bit on what is meant by “truth”.

Pingback: August 2017 Round-Up: History, Memoir and Biography – Australian Women Writers Challenge Blog