2018, 339 p.

I am old enough to remember when Australia’s wool trade was a source of national pride. Primary school children would send off to the Wool Board (or whatever it was called at the time) to receive a project pack that included samples of wool at different stages of processing: straight off the sheep’s back, washed, combed, and carded, right through to a piece of woven material, all in a big envelope. John Macarthur was on our $2.00 notes, with a whopping great merino beside him, with William Farrer on the other side with his wheat, symbols of the importance of the pastoral industry and agriculture to Australia’s history and economy.

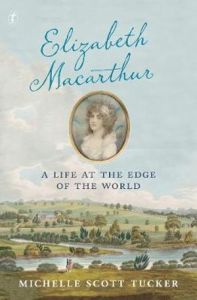

But it was all very male-dominated. I first heard of Elizabeth Macarthur when I visited Elizabeth Farm in Parramatta about twenty years ago. It struck me then, listening to the guide, that much of the glory that attached to John Macarthur more rightly should be shared with her, given that he spent so many years overseas. In this book Michelle Scott Tucker brings Elizabeth Macarthur to centre stage as businesswoman, wife and mother, dealing with a difficult and eventually mentally ill husband.

The book opens with a premature childbirth at sea on a convicts’ ship, where Elizabeth Macarthur, a gentleman’s daughter, is the only woman on board. She, her husband John and her infant son were sailing as part of the Second Fleet to Sydney Cove where he would take up his position as a commissioned officer in the New South Wales Corps. As was common right up to the 20th century, Elizabeth kept a ship board journal, and Tucker contextualizes this journal well in explaining what shipboard life was like in the Second Fleet, and the social distinctions and rigidities within the hierarchy of the passengers. There were tensions, slights and confrontations and even here we see John Macarthur’s hair-trigger sense of honour which was to blight and shape the social life of his family within the colony.

I must confess that even though I’ve read about the early days in Sydney Cove, I didn’t realize the significance of the navy/army distinction as the basis of much of the dissatisfaction at the elite level within the colony (and come to think of it, probably in the other colonies I have read about as well). Macarthur quickly moved into the centre of the social life of ‘good society’ and was deeply implicated in the Rum Rebellion against (Navy) Governor Bligh led by the New South Wales Corps (Army). His involvement in local politics at a time when official power was exercised through the Colonial Office meant that he spent many years overseas, clearing his name and honour, and then in a sort of political exile that in effect split the family. As was common at the time, young boys were sent ‘home’ for their education, and for many years Elizabeth kept the properties going, soothed the local politics as much as she could and built up the family enterprise on this ‘edge of the world’, while her husband and a number of sons did the same back in England. When a son went off ‘home’ as a seven year old schoolboy, sometimes he never returned to Australia. Instead, opportunities brought about through extended family connections and marriages kept him back in the’ old country’.

Colonial histories in the past, tended to focus on the world of men. In recent years there has been more attention on the networks of influence, opinion and behavioural constraints that operated in colonial societies. While John Macarthur had his own political involvements, so too did Elizabeth Macarthur within the women’s networks of early Sydney. His behaviour directly impacted on her own friendships and status, and Tucker describes this well. Although aimed at a popular, as distinct from academic audience, the bibliography at the back of the book shows that she has read widely on early Sydney, although I’m surprised that she doesn’t reference Kirsten McKenzie’s Scandal in the Colonies which would have fitted in so well here.

The family correspondence has been kept, and it is through this lens that Tucker shapes her reading of Elizabeth Macarthur. Family correspondence has its limitations, of course, and these were exacerbated by distance and slow communications. For letters to friends, who had never -and would never- see Australia, there is an ‘other-worldliness’ to her situation. In letters to her sons, who did not need to have things explained, the maternal relationship still held. In letters to and from her husband John, beyond reporting events and business, the politics of their relationship was interwoven with the family mores of the time.

In several places, Tucker notes that Elizabeth Macarthur has not commented on particular events or people. This is always frustrating, perplexing and yet these silences often reflect something of the personality and times of the writer. Sometimes Tucker surmises “she must have….” which I found myself resisting. One of the questions of biography, is how much we can claim a common worldview at the emotional level with people of the past, especially in the light of recent work in this field.

In this regard, the book reminded me of another biography of a ‘colonial wife’: that of Anna Murray Powell, wife of the Chief Justice in Upper Canada in the 1820s in Katherine McKenna’s A Life of Propriety: Anna Murray Powell and her family 1755-1849 (my review here). A more academic text than this one, McKenna uses the family correspondence of the Powell family to examine how as matriarch and wife, Anna Murray Powell grappled with a young daughter whose very public and unseemly infatuation with the future attorney-general. As with Elizabeth Macarthur, there are silences and omissions about the things we are most curious about as 21st century readers, particularly when dealing with a socially unacceptable situation – for Anna Powell, the behaviour of her daughter, and for Elizabeth Macarthur, her husband’s mental illness.

Elizabeth Macarthur was a mother, with her love stretched between ‘home’ and this new life very much on the edge of the world. She was a wife, displaying affection, but also exasperation and diffidence when dealing with a difficult husband. Within her own family relationships, she dealt with distance and madness. She was an astute businesswoman, handling a large enterprise in the colonies while her husband had all the financial power. Tucker has given us a rounded picture of Elizabeth Macarthur, one that is faithful to the times and also to the sources.

My rating: 8.5

I have included this review on the Australian Women Writers challenge

I have included this review on the Australian Women Writers challenge

By coincidence I’ve just finished reading a bio of a New Zealand couple and I felt the limitations of not really knowing the female PoV. Even when they wrote letters, knowing that they would be shared often made them self-censor a bit…

Great review RJ. I was interested in your comment “Sometimes Tucker surmises “she must have….” which I found myself resisting. One of the questions of biography, is how much we can claim a common worldview at the emotional level with people of the past, especially in the light of recent work in this field.” I guess one of the things I liked about Tucker’s biography was that she heralds these gaps, and I didn’t mind the “she must have” because I think that while circumstances are different in different area emotions are more universal? There’s a fine line I’m sure where circumstances and emotions are closely enmeshed but at least by heralding the gap the way she does we know which aspects of her biography more open to re-interpretation?

I interviewed Michelle and she was very clear about “not making stuff up” and about flagging where she was speculating. In passing, I think Elizabeth was the only free female on the voyage out. My recollection is that the Macarthurs were assigned a cabin below decks with the female convicts.

Pingback: 2019 Australian Women Writers Challenge Completed | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip