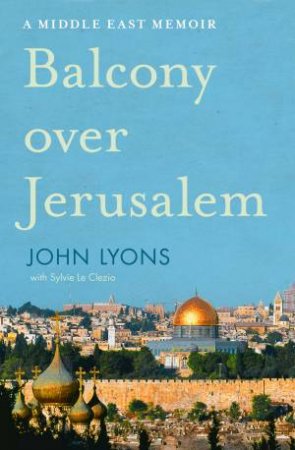

This book, co-written with his wife Sylvie Le Clezio in 2017 was another amongst the selection of books handed to Australian MPs by a number of prominent local writers. It is a memoir of the six years that Lyons spent based in Jerusalem as Middle East correspondent for the Australian, not a newspaper that I read often. He has worked for most of the media groups in Australia: Murdoch with the Australian, the Sydney Morning Herald and now for the ABC as their Global Affairs Editor. I must say that I will now watch his reports from the Middle East in the wake of October 7 with added interest because, not only does this book deal with the swirling constellation of Middle East politics between 2009 and 2015, but also it highlights the heavy influence of the Israel lobby in Australia in shaping the news for an Australian and Jewish/Australian audience to reflect an even harder line here than in Israel.

The book is named for the large balcony in their apartment that overlooked a vista which encapsulated Palestinian/Israel history: Old City of Jerusalem, modern Jerusalem, the headquarters of the United Nations, and the concrete wall that separates Israel from the occupied West Bank. In front of their balcony was the ‘peace park’, where six days of the week Israelis would place their picnic baskets on the upper parts of the park, and the Palestinians would picnic on the lower parts. Except for Friday evenings, when on the sound of a siren announcing Shabbat, Israelis would leave the park and walk home for their Shabbat dinners. On cue, the Palestinians would appear carrying plates of kebabs and tabouli and move to the higher parts until, on Saturday evening, the Israelis returned, taking up their place on the top of the hill, and the Palestinians would move back down again.

In his opening chapter he declares that

As for my own perspective, I approach reporting of Israel from a ‘pro-journalist’ stance. I’m neither ‘pro-Palestinian’ nor ‘pro-Israel’. My home is in Australia, on the other side of the world. To use an old Australian saying, I don’t have a dog in this fight. (p. 12)

This is not, however, the conclusion that he comes to by the end of the book, which has documented the pervasiveness of Israel control, particularly in the West Bank, and trenchantly criticized the role of Benjamin Netanyahu in particular for making a two-state solution impossible. In spite of Israeli finessing to obscure the fact by withholding and withdrawing Palestinian residency status in the West Bank, the demographic tipping-point between Israelis and Palestinians has been reached: during Lyons’ stay the number of Palestinians in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza equalled (or, depending on your sources, passed) the number of Jews in Israel and the West Bank. As he sees it, in coming years, there will be tragic consequences of this policy.

This tragedy now seems inevitable. Almost 3 million people in the West Bank cannot be denied all civil rights for more than 50 years without dire consequences and almost two million people in Gaza cannot be locked forever in the world’s largest open-air prison. One day many of those five million people will rise up. (p. 357)

As Middle East correspondent generally, his brief extended to countries beyond Israel. He was there to witness the Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent crackdowns in various countries and the political permutations in Iran, Egypt, Libya, Lebanon and Syria. His conclusion was that the Arab Spring failed because the step between dictatorship and democracy was too large, especially without the in-between establishment of independent institutions like police forces and civil services (p.355).

However, his major emphasis is on Israel, and the politics that have shaped the United States response, which flies in the face of world opinion which is gradually hardening against Israel (and, I would suggest, has hardened even further in the last year). He writes honestly and persuasively about the power of the Israeli-lobby group, particularly the AIJAC (Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council) headed by Colin Rubenstein, in pressuring the Australian media and targetting particular journalists (including him) in their reporting. He writes about its influence on politicians, especially through the generous ‘study’ tours that are provided to MPs – several of whom have attended on multiple trips hosted by Melbourne property developer Albert Dadon- which give a one-sided view of the Israeli/Palestinian situation. He particularly focuses on Labor politicians- Rudd, Carr, Gillard- because of the mismatch between party policy, the views of party members, and Government policy- and the way that Israeli policy became caught up in the leadership ructions during the first decade of the 21st century. He highlights the importance of language used in reporting- for example, whether East Jerusalem is described as ‘occupied’ or not and whether ‘occupied’ has a capital ‘O’ or lower case ‘o’; or whether SBS should use the word ‘disputed’ territories.

As might be expected, this book was criticized by politicians and commentators who take a different line to him. But, as he says

…those who’d read my reports over these six years could have been confident that they were reading facts, not propaganda….That, in the end, is what journalists should do: report what’s in front of them. Then it’s over to the politicians and the public to decide what they do with that information. But without facts, they cannot know what they are dealing with (p.356)

Having read this book, and knowing his own personal and professional opinion, casts a different light on his dispassionate, fact-based reporting for the ABC, reporting that saw him named Journalist of the Year at the 2024 Kennedy Awards. On the one hand, it fills me with admiration that he’s even able to report so calmly and authoritatively. On the other hand, though, I’m now aware of the editorial pressure and careful vetting that would have gone into his reports- and no doubt, for this book. It stands the test of eight years well, especially the last 18 months, and is a sobering analysis of not just the ‘facts’ of Israeli/Palestinian conflict day after day, but the political and public relations filter that screens and shapes what we receive as readers and viewers- and our responsibility to question it.

My rating: 8/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

Read because: it was one of the 5 books given to MPs, but I have had it on reserve at the library for months previously.