Since the Orange One has launched his mayhem on the world – did this second presidency really only start in January?- China and Xi Jinping are presenting themselves as a calm, considered and stable presence on the world stage in comparison. It’s a seductive thought, but after reading this small book, I came away convinced that there is a fundamental difference between China and Western democracies in terms of both means and ends that we ignore at our peril.

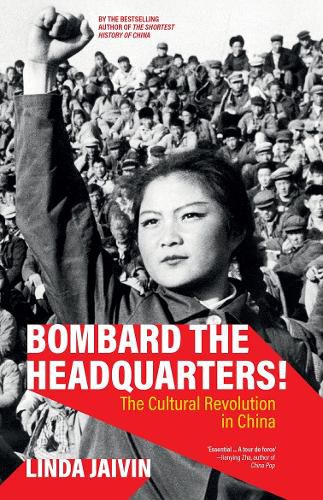

Many historians mark 16 May 1966 as the start of the Cultural Revolution, when Jiang Quing (Mao’s fourth wife) and Mao circulated a document amongst the Party members which warned of ‘counter-revolutionary revisionists’ who had infiltrated the Party, the government, the army and cultural circles. This document was only made public a year later, but it was popularized in August 1966 by “Bombard the Headquarters”, a short text in written by Mao Zedong himself and published widely. It was a call to the students, who were already confronting their teachers and university lecturers, exhorting them that ‘to rebel is justified’. Yet the headquarters he was urging them to target were the headquarters of his government; of his party. Within three months there would be 15 to 20 million Red Guards, some already in university, others as young as ten. They were urged to ‘smash the Four Olds (old ideas, culture customs and habits) to make was for the creation of a new revolutionary culture. Mao did not explicitly call for the formation of the Red Guards, but he harnessed them as an alternative source of power to the government and, at first, beyond the control of the army until it also joined in the Cultural Revolution in January of 1967.

With Khruschev’s denunciation of the cult of Stalin, Mao felt that Russia had betrayed the revolution and that China needed to return to the dictatorship of the proletariat. Even though 1966 is seen by many as the starting point, Mao had been moving towards this point for several years, moving against the deputy mayor of Beijing and historian Wu Han, removing the People’s Liberation Army chief of staff and premier Luo Ruiquing, and splitting with the Japanese Communist Party because it failed to call out Soviet revisionism.

Some of his party colleagues, most especially Liu Shaoqui, Deng Xioping and Zhou Enlai, held qualms about Mao’s call for continuous revolution led by the Red Army. And well they might have, because quite a few of Mao’s judgment calls – The Great Leap Forward and the Hundred Flowers Campaign- brought unseen (to him) consequences, and the schemes ended up being abandoned. But despite any reservations his colleagues may have held, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution went forward, with the Red Guards murdering 1800 people in Beijing alone in Red August 1966. The Red Guards were joined by the workers in late 1966, and the Army in January 1967.

At a dinner to celebrate Mao’s 73rd birthday on 26 December 1966, he proposed a toast to “all-out civil war and next year’s victory”. He got his civil war. Children denounced parents; both the Red and the conventional army split into factions. The targets of the Cultural Revolution were the Five Bad Categories- landlords, rich peasants, counter-revolutionaries, bad elements and ‘rightists’. Temples, churches and mosques were trashed; libraries set alight, hair salons and dressmakers’ shops attacked, and even the skeletons of a Wanli emperor and his two empresses were attacked and burned. The verb ‘to struggle’ came to have a new meaning as ‘enemies’ were “struggled” into the airplane position, forced to bend at the waist at 90 degrees with their arms straight behind, with heavy placards hung around their necks and hefty dunce caps on their heads. Teachers, academics, musicians, writers, local officials were all ‘struggled’, with day-long interrogations that ended with instructions to return the next day for more after being allowed to go home overnight. No wonder so many people committed suicide.

By September 1968, the civil war was declared over, with ‘the whole nation turning Red’. However, with the deteriorating economic situation, and with a perception that people living in the cities were not pulling their weight, Mao decided that ‘educated youth’ needed to receive re-education by the poor and middle-class peasantry (p. 68). In 1969 as many as 2.6 million ‘educated youth’ -including present-day president Xi Jinping- left the cities for the country side. Some did not have to go too far from home, but others were exiled to the brutal winters of the Great Northeast Wilderness, or the tropical jungles of Yunnan in the south-west. Some villagers were ambivalent about these ‘soft’ teenagers, although they welcomed the goods and knowledge that they brought with them. The young people were often shocked by the poverty and deprivation in the villages, which contrasted starkly with the propaganda of the happy prosperous countryside they had accepted.

The Cultural Revolution had morphed in its shape, with the 9th Party congress declaring that the Cultural Revolution was over in April1969, and Mao criticizing his wife Jiang Quing and her radical associates in the ‘Gang of Four’ in May 1975. The outside world was changing too. A border war with USSR in March 1969 provoked fears of nuclear war, and the United Nations recognized the People’s Republic of China over Taiwan. President Nixon visited China in February 1972 (Australia’s Gough Whitlam, then opposition leader, had visited in July 1971) and Mao died in September 1976, eight months after the death of Zhou Enlai. In 1981 the Party declared that the Cultural Revolution had been a mistake, and that Mao had been misled by ‘counter-revolutionary cliques’. All at the cost of at least 4.2 million people being detained and investigated, and 1.7 million killed. Some 71,200 families were destroyed entirely. It has been estimated that more people were killed in the Cultural Revolution than the total number of British, American and French soldiers and citizens killed in World War II (p. 106)

The Cultural Revolution may seem an event of the 20th century it’s not that far away. Xi Jinping and his family were caught up in the Cultural Revolution, and tales of him toiling alongside the peasants in the countryside is part of his own political mythology. We here in the West are well aware of the Tienanmen Square protests of 1989, but there is no discussion of them in China. When Xi Jinping took power in 2012, discussion of the Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward and the resulting famine, were all increasingly censored. Xi Jinping abolished the two-term limit to presidential office in 2018, making it possible for him to be President for life. New generations of nationalist fanatics have arisen, likened (for good or bad) to the Red Guards.

This is only a short book, running to just 107 pages of text. In its formatting and intent, it is of a pair with Sheila Fitzpatrick’s The Death of Stalin (reviewed here), and both books deal with hinge-points that, although taking place some 50 years ago, resonate today with even more depth. As with Fitzpatrick’s book, Bombard the Headquarters opens with a timeline and a cast of characters, but I found the brevity of Jaivin’s character list made it harder to establish the various protagonists in my mind, exacerbated further by unfamiliar names. What I really did like was the way that she interwove the stories and experiences of individuals alongside the ‘massed’ nature of this revolution. When we see the huge crowds of people in Tiananmen Square, and the chilling precision of the Chinese army at the parades that dictators are so fond of, it is hard to find the individual, but she has worked hard to keep our attention on the people who lived through, suffered, and did not always survive such a huge experiment in social engineering.

My rating: 8/10

Sourced from: Review copy from Black Inc. books, with thanks.