2019 335p.

SPOILER ALERT

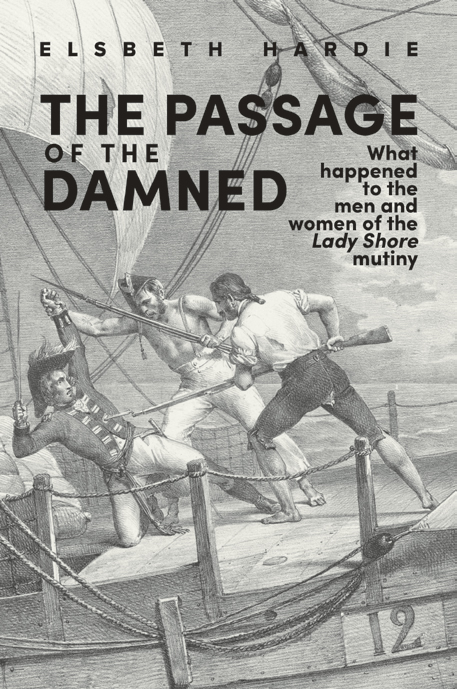

At a time when we’re all locked in our houses because of coronavirus, it seemed apposite to read about other people who had also been locked down. I had been sent this book for review an embarrassingly long time ago, and so I settled down with it, expecting to read about a convict transport ship bearing mainly women passengers bound for New South Wales. I was surprised to end up in a completely different continent, with many of its female convict passengers integrating into a Spanish-speaking community, in many cases leaving their convict history far behind. It’s quite a rattling tale, and one with which I was not familiar.

The convict ship Lady Shore set sail from Portsmouth on 22 April 1797 with 66 female prisoners, 2 male prisoners, 40-something ship’s officers and some 70-odd members of the New South Wales Corps, some of whom were accompanied by their wives and children (the sources give differing numbers). It never made it to Sydney. On 1 August the ship was seized by mutineers, largely drawn from amongst the French, German and Spaniard prisoners of war who had been conscripted against their will into the New South Wales Corps. One wonders why the British government ever thought that this would be a good idea. With the rallying cry “Vive La Republique!” they took control of the ship near the Brazilian coast, supplemented by other disaffected Irish and English members of the NSW Corps. The captain, chief mate and one of the mutineers were killed. A longboat, containing 29 people including officers, soldiers and some sailors, wives and children, was set adrift from the commandeered ship, reaching shore at San Pedro Rio Grand the next afternoon. They gradually made their way to Rio de Janeiro, and in many cases, back to London where the mutiny was reported to the government.

Meanwhile, the mutineers and their cargo of female convicts set sail for Montevideo. Because France had defeated Spain during 1794 as part of the Revolutionary Wars, the mutineers felt (correctly) that they would receive the protection of the Spanish government, and they were eventually released, and even financially benefited from taking the ship as a prize of war. One of the ringleaders finally faced British justice and was hanged for the murder of Captain Willcox when he was apprehended some time later. There was little British concern about the female convicts, many of whom converted to Catholicism and blended into Buenos Aires society.

The author, Elsbeth Hardie is a journalist in New Zealand. Before writing this book, she had written another non-fiction book The Girl Who Stole Stockings, based on the life of her maternal ancestor, Susannah Noon, who was sentenced to transportation for the theft of stockings when she was twelve years old. Although this 1794 journey of the Lady Shore carried female convicts, they play a minor role in this book- as, indeed, they did in the eventual outcome of the mutiny.

The book is written as a chronological narrative history, divided up by subheadings but not into separate chapters. While this does drive the action forward, there is little shaping of an argument as such. The author describes the drawn-out nature of imprisonment prior to embarkation on a convict transport ship, and gives a good picture of the New South Wales Corp ‘enlistment’ which verged on impressment during the Napoleonic Wars, when any half-decent soldier was deployed in fighting rather than guarding convicts on the other side of the world. I did find myself transfixed by the ‘what next?’ nature of the first part of the book, especially during the mutiny and the immediate aftermath. It was much written about at the time, by both participants and in the newspapers, and Hardie balances competing (and somewhat self-serving) narratives to give a detailed account of events.

The narrative splinters somewhat when it comes to tracing the outcomes for the women convicts. Here Hardie relies- with appropriate acknowledgement- on the work of Argentinian scholar Joseph M. Massini Ezcurra in the 1950s, whose work was taken up by Juan M. Méndez Avellanada writing from the 1980s and whose book Las Convictas de la Lady Shore was published in English in 2008. When the female prisoners arrived, they were located in a Bethlemite convent called La Residencia in Buenos Aires. From there, they found work as servants in Buenos Aires families, married, and disappeared into respectability or – in relatively few cases – moved into prostitution and petty crime. Most converted to Catholicism, either through conviction or as a survival mechanism, and blended into society. Their names in the records were often rendered into their Spanish translation e.g. Susannah King became Susana Rey; Lucy Whitehouse became Lucia Blanco. Sometimes their names were written phonetically; other women reverted to their maiden names or adopted another names. At this point, the genealogical detail of the hunt tends to swamp the narrative.

The discussion of sources appears, rather strangely, at the end of the book. This could be the author’s way of bringing the story into the 20th and 21st century. Texts and sources continued to appear as recently as 2012, when Sotheby’s sold the diary of Thomas Millard, the ship’s carpenter, which was purchased by a private buyer and has disappeared since. It was a strange way to finish the book, and I felt that it cried out for a concluding chapter, drawing out the major themes and rounding off the story.

I found myself likening this book to Cassandra Pybus’ Truganini (my review here), not in terms of content, but in its avoidance of secondary literature and sidestepping of academic work that would have added so much to this book. In this case, I don’t know whether it is because Hardie has a journalist, rather than historian, background or whether, as in Pybus’ case, it is a more deliberate authorial choice. In her descriptions of the prison system and the women’s crimes, I found myself thinking back to E.P. Thompson’s Whigs and Hunters (my review here) which explains the ‘mission creep’ of the Black Act in the protection of property and the distortions it created in sentencing decisions and leading to so many commutations of life sentences to transportation. Greg Dening did such an excellent job in talking about naval discipline, leadership,character and mutiny in Mr Bligh’s Bad Language, which I would have loved to have seen Hardie draw on when discussing the rather pusillanimous (and young) Ensign William Minchin of the NSW Corps. And what would Kirsten McKenzie, one of my favorite historians and author of Scandal in the Colonies and A Swindler’s Progress (my review here) done with Major James Semple, imposter extraordinaire and one of her most robust characters and informants? In Semple’s life (or rather, lives), and in the lives of the women convicts, Hardie gives us multiple examples of the slipperiness of identity in colonial port cities that McKenzie explores so well.

Nonetheless, I am again wishing for a different book, rather than the one I have in my hands. By her focus on one example, Hardie draws a vivid picture of global politics as it played out on the high seas during the Revolutionary Wars. She captures well the coerced nature of life in the NSW Corps, and highlights the elisions between role of prisoner, guard, sailor and soldier. Far from a lonely ship sailing off onto the high seas, she paints a picture of a network of ships, criss-crossing the globe and circulating different ports, not unlike those maps of flight paths in the back of the airline magazine when we used to be able to fly. Particularly the first half of her book is engrossing narrative history, and I must admit that I have not often had to put ‘Spoiler Alert’ at the start of a review of a history!

Sourced from: review copy from Australian Scholarly Press.

I have included this on the

I have included this on the