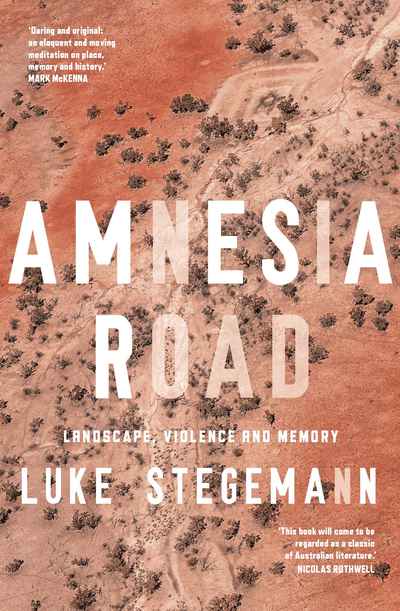

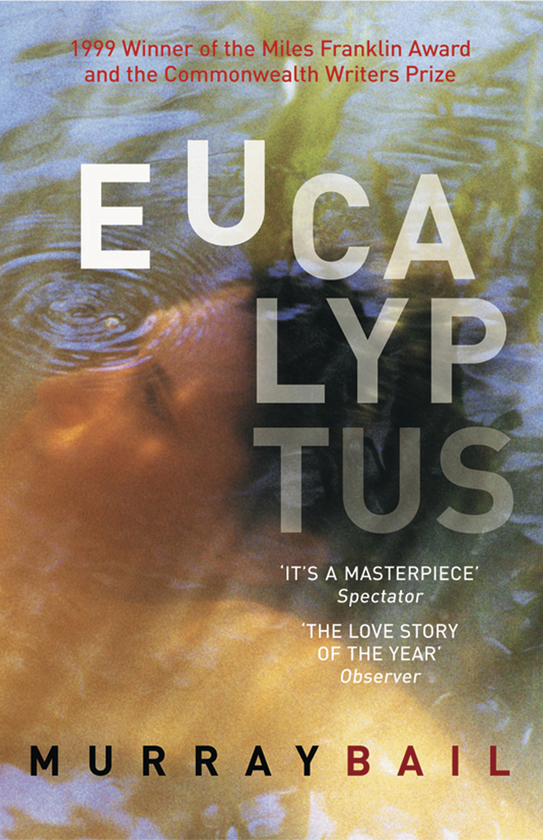

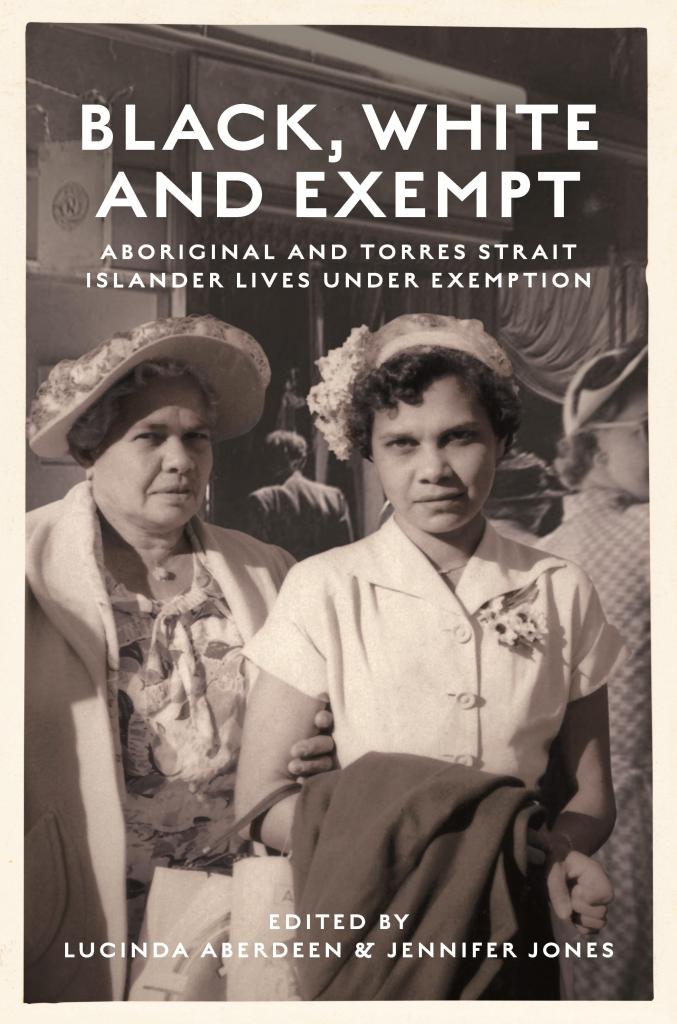

South-western Queensland and the rural backlands of Andalusia in Spain are two landscapes and histories that rarely mentioned in the same breath. However, they are not dissimilar to look at: indeed, the image on the front cover could be of Australia’s red centre or the arid desert regions of Andalusia. I suspect by the red tones that suffuse the photograph that it is of Australia, but blood is red too, and it has soaked into the landscape of both settings. In Queensland there were the barely acknowledge massacres of indigenous Australians as settlers moved westward; in Andalusia, there were the bloody atrocities on both sides during the Spanish Civil War.

There are few other people whose knowledge spans both locations, apart from fleeting visits by most travellers. This is where Hispanist and cultural historian Luke Stegemann comes in. He travels the backroads of Queensland as a boxing referee, while he refers to Spain as his ‘second patria‘. Deeply familiar with both, he brings them together in what is described as a “literary examination” of landscape, violence and memory in the two places.

He doesn’t actually describe what a “literary examination” or a “literary meditation” is, but I assume that it is a drawing together of the visions of other writers about an event or place. Certainly, he does reference other authors, but this is no mere desktop activity. He physically visits many of the places that he writes about, mainly as an outside observer. He marries the literary and experiential into a discursive, poetic, beautifully shaped exploration of questions about the memories that a landscape can hold, and the tenacity with which those memories take hold, despite the tacit or overt agreement to deny them.

This book employs two scenarios- the mid-nineteenth century pastoral frontier of south-west Queensland, and a series of early twentieth-century civilian massacres in southern Spain – as pathways towards examining the ways history is turned over and inspected, sometimes with fascination, sometimes with disgust, and its angles then polished for specific cultural and political purposes. Both scenarios are at the centre of contemporary debates around the need to tell, and approved methods of telling, troubled – perhaps better to say infamous – aspects of national history.

p.6

The opening chapters wrestle with the ideas of memory and forgetting, memorializing through graveyards and forgetting through unnamed massacre sites. He shuttles between Australia and Spain, using the writing from one culture to illuminate the other. In places this seems like a linguistic game, with chapters titled ‘The verb that has no name’ or ‘The Language of Eden’. The passing of generations and their knowledge is described grammatically:

The past tense soon closes down the present perfect nature of that claim: people have seen becomes, forever, people saw. Descendants remain, but the last of the witnesses are gone. The final death is often unremarked for who knows who is the last of the witnesses?…Each day, each year, each decade, periods of history move further away and we are left with an imperfect detritus. Windows are closed, doors shut, voices silenced, graves sealed.

p.34

The book is mainly based on the Australian experience, with the Iberian example used as a point of both comparison and contrast. The heart of the book lies in the two long chapters ‘Threnody’ (which I confess I had to look up – it means “a wailing ode, song, hymn or poem of mourning composed or performed as a memorial to a dead person”) and ‘Iberian Hinterland’.

The ‘Threnody’ chapter, at 50 pages, has the structure of a guided tour across the landscape of south-west Queensland. At each stop, he gives us a description of the landscape and a short history of the ‘interactions’ that took place there. He intersperses this with the local and amateur histories of these places, which generally celebrate the ‘progress’ of settlement and the ‘success’ of ‘dispersal’.

We have a duty to look unsparingly at the acts committed. We can now both see and understand the absurd vanity of the acquisitive graziers, to say nothing of the wretched illegality of their land grabs; nevertheless our contemporary morality is of limited use in grappling with this history. Unavoidably, the expansion of the Europeans across south-west Queensland involved tremendous cruelty and episodes of outright violence that mark our national history, though this fact must be tempered with the knowledge of acts of tenderness and attempts at understanding on both sides, and what were often immediate and close relationships between Indigenous people and settlers.

p. 85

Nonetheless, as he points out, in order to considered these acts of goodwill, “it is first necessary to climb over the bodies. The toll cannot be avoided.” P. 118 On the Massacre Map produced by the University of Newcastle, the area of South West Queensland is not studded with dots (as the coastal areas are) but when you do click on the massacres, they are of huge numbers of people. I have read of frontier violence before, but it was generalIy deployed against small groups of warriors, or family groups of women and children. I hadn’t imagined 300 people being massacred, as at Bulloo River. Imagine it. The vision is horrifying.

In the succeeding ‘Iberian Hinterland’ chapter, at 63 pages in length, he takes a similar approach, although here he overlays the bloody Civil War history with the tourist itinerary, which exists largely oblivious to what happened less than a century before. I remember reading in the guide book that I took with me to Andalusia just a few years ago, there was still sensitivity about the Civil War, and to not ask pointed questions. But unlike the anonymity and paucity of Indigenous deaths in Australia, there is “a paper trail and a line of bones” that testify to a national total of some 115,000 murdered behind nationalist lines, and 55,000 behind Republican lines (p.135). With the passing of the Law of Historic Memory in 2007 there has been a deliberate political decision that the tacit silence about this slaughter will be broken; that bodies will be exhumed; that Franco will be shifted from the Valley of the Fallen to a private family vault.

Just as there is no turning away from the brutal slaughter of Indigenous people in south-west Queensland, there is no turning away from the indiscriminate killing of tens of thousands of innocent people in the first months of Spain’s civil conflict. And it has been the slow revelation of these details, the political environment into which they have been released, and the arguments they have triggered around questions of memory, truth, justice, compensation and reconciliation, and where these might find their place in a modern democracy, that have added weight to what might otherwise have been just one more collection of twentieth-century bones- anonymous, roadside or forest-deep- abandoned to their violent quiet.

p. 137

Stegemann sees a similar movement at work here in Australia too, as the Great Australian Silence (in Stanner’s words) is finally being broken down. In particular he points to the Uluru Statement (awarded the 2021 Sydney Peace Prize but still shamefully suspended in limbo four years later). But he points out that reconciliation is hard work. The passing and implementation of the Law of Historic Memory in Spain has been fraught, and is likely to become even more so with the rise of populism. In Australia, the ideological ravine scours ever deeper with social media and a shrill press.

This really is a beautifully written book. You could open any page and find a paragraph that is beautifully crafted and insightful. It has high expectations of the reader. The dual emphasis on Indigenous Australia and Andalusia particularly appealed to me because my interests align along those tracks as well, but also because it illustrates the way that our learning in one field illuminates and enriches the other fields of knowledge that we encounter.

My rating: 9/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library