When I sat down to think about it, my family has had more contact with Freemasonry than I realized. I certainly knew that my grandfather (whom I never met) was a staunch Lodge man. One of the few times my father really lost his temper with us as children was when we found his father’s Lodge case, opened it, put on our grandfather’s spectacles and wore his apron draped over our heads and paraded around on our billy carts. My grandfather had encouraged my father to join the Masons, but Dad went a couple of times and didn’t like it. One of the few social functions that I remember with my father’s family was a 21st birthday party of a distant cousin that was held in the Loyal Orange Hall, where I was bemused by the name of the hall, given that it wasn’t orange at all. On my husband’s side, his father joined the Freemasons in his small country town, because a man had to be either Catholic or a Mason.

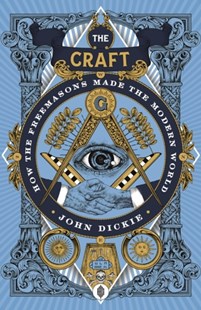

So in our family, our fathers and grandfathers were all involved, to varying degrees of commitment, with the Masons but it was not unusual for the 50’s and 60’s. As John Dickie points out in his book How the Freemasons Made the Modern World, by the dawn of the 1960s in America, one in twelve adult males was a Freemason (p.351). Although there were nearly twice as many Freemasons in America as in the rest of the world combined, Australia was not immune to the popularity of Freemasonry either. Certainly in the colony of Port Phillip prior to the gold rush, the freemasons played an important role in marking the construction of civic buildings, with elaborate rituals accompanying the laying of foundation stones including the first purpose-built Supreme Court in July 1842.

When I first saw the title How the Freemasons Made the Modern World, I thought that the author, whose grandfather was a Freemason, was over-reaching somewhat. His focus is mainly on Britain, Europe and the United States but given that these were the colonizing powers, then Freemasonry’s reach did touch the whole modern world. What was fascinating was the different complexion it took on in so many countries across the world.

For a movement with its origins supposedly in antiquity, there’s a lot of different origin stories at play. One is that masons are the direct descendants of medieval stonemasons, like those who worked on Salisbury, Lincoln and York Minster cathedrals in “merrie England”. Except that the stone masons, as peripatetic workers, didn’t actually have a “guild”. They did, however, have a rich store of rules, symbols and myths known as the “Old Charges” which includes an origin story from a lucky dip of sources – Genesis and the Book of Kings from the Old Testament; the legendary Hellenic figure Hermes Trismegistus who re-discovered the geometrical rules of masonry after Noah’s flood; Euclid; and King Solomon and his chief mason Hiram Abiff.

Then there’s Scotland’s influence, with King James and his Master of Works William Schaw. Schaw established secret “lodges” of master stonemasons, charged with building the Chapel Royal at Stirling, the earliest Renaissance building of its kind in Britain. He instituted the Art and Science of Memory (based on the Memory Palace concept) based on embedding secrets and codes into the masonic Lodge itself- columns, patterned floor etc. Once it spread from Scotland to England during the reign of Charles I, elements of Rosicruciamism were added and the principle known as ‘acception’ allowed non-masons of high standing to be adopted or ‘accepted’ as masons. The Grand Lodge was created by Whig power-brokers, who had ties to the Royal Society and the magistrates’ benches. It established a constitution in 1723 which included rules and a fantastical history of Freemasonry, claiming Adam and Noah, the Israelites generally and Moses as masons. Patronage bestowed on the Craft from the very top of the social scale ensured that Grand Masters were Lords, Viscounts, Earls, Marquesses, Dukes and even Princes.

It spread to France, where added to this existing lore was the claim that the crusading knights rediscovered the secrets of Solomon’s Temple and the Craft while they were in the Holy Land, imbuing it with the ideals of chivalry. The Lodges reflected the more fixed nature of the social classes in France, and traditional forms of Catholic chauvinism. Then in Germany, we had the introduction of the Illuminati, founded by Adam Weishaupt, who initially detested Freemasonry, but later moved to infiltrate them to promote the ideas of the French Enlightenment. Meanwhile, in Italy, Napoleon’s brother-in-law Joachim Murat and his brother Joseph Bonaparte used lodges as a form of networking. In the wake of the French Revolution, quasi-Masonic political brotherhoods appeared in Europe’s trouble spots including the United Irishmen, the Greek Filiki Eteria and the Russian Decembrists- and most infamously, the Charcoal Burners and the Cauldron-Makers in Naples which morphed into the Mafia.

Meanwhile, in America, George Washington used Freemasonry as a civic religion, and was venerated by generations of American masons. Freemasonry’s principles of self-betterment and the brotherhood of all men meshed in with the ideas exemplified by the Declaration of Independence. Such ideals didn’t extend to Afro-Americans, though, and Prince Hall Freemasonry emerged as a completely separate, black Freemasonry. In India, Parsi, Sikh and Muslim initiates were admitted to the Craft, and to a lesser and more-contested extent, Hindus as well, although there was an undercurrent of bigotry as well. Meanwhile, Freemasonry spread to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand- and Melbourne.

What I had absolutely no idea about is the oppression that Freemasonry endured at the hands of twentieth-century dictators like Mussolini, Hitler and Franco (as well as in Hungary, under the Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar and in Vichy France). As he points out, it may not have been Freemasonry in itself that brought it under the scrutiny of dictators, but just as much the progressive ideas of brotherhood, humanitarianism and civil society that Masons often held alongside their Freemasonry. And certainly, in Nazi Germany and the countries that adopted Nazism, Lodges participated in anti-Semitism and Aryanization as well. Franco’s Spain exhibited the most virulent hostility against Freemasonry, and it remained illegal in Spain until democracy returned in the late 1970s/early 1980s. Meanwhile, in Italy Licio Gelli, the Venerable Master of the Lodge Propaganda 2, or P2, was involved in a string of scandals and protection rackets, conspiracy and terrorism.

One of the hallmarks of Freemasonry has always been secrecy. This gave rise to lurid rumours about what went on behind the walls of the temple, and also opened Freemasonry and its exposés, to trickery and forgery. I remember, while I was being told off by my father for my broaching the privacy of my deceased grandfather´s Lodge case, that we couldn´t possibly understand the importance of what was in it because it was all a sworn secret. Yet some fifty years later, I went with a member of the historical society on a tour of the local masonic temple, where he was quite open about what went on there. Likewise, in the second chapter of this book, Dickie explains about the degrees, the rituals, the handshakes, and names the words that must never be uttered. As he says:

The purpose of Masonic secrecy is secrecy. The elaborate cult of secrecy within Freemasonry is a ritual fiction. All the terrifying penalties for oath-breaking are just theatre- never to be implemented…In the end, while Masonic secrecy has very little to it in the pure sense, it is also all the many things that, throughout history, and across the world, both the Brothers and their enemies have made of it.

p.25, 26

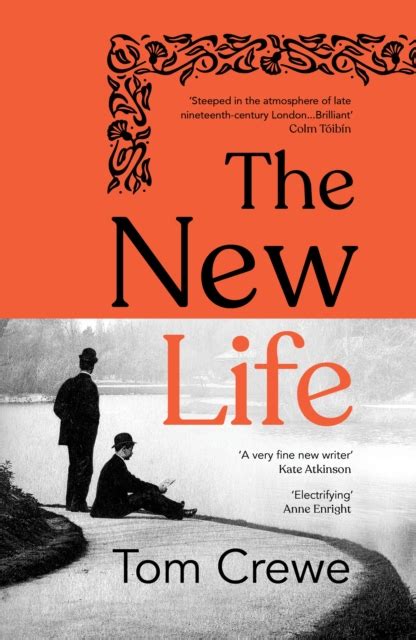

The final chapter of the book is titled ‘Legacies’, and you certainly go away with a sense that, despite blips of interest generated by Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code and The Lost Symbol, Freemasonry doesn’t have much of a future. Masonry has increasingly become a phase that men go through, rather than a long-term, lifetime commitment (as with my grandfather). Although there have always been small, female Lodges especially in France, the overwhelming image of Freemasonry is male, with the good little woman at home putting the kids to bed while Dad is off doing his Mason thing. It may seem an extraordinary thing that the Grand Orient of France welcomed Sisters with equal Masonic status to their brothers in 2010, with architect Olivia Chaumont the first Sister with full Masonic status, elected a few months later as the first woman to sit on the throne of a lodge master. Although women have followed in her footsteps, Chaumont is a trans woman, who had originally embarked on Freemasonry as a male. The Museum of Freemasonry in the Grand Orient building in Paris devotes only two sentences to the decision to admit women, and there is no mention of Olivia at all. As Dickie notes wryly “Even when Freemasonry changes, it would seem, it is reluctant to change its story”. (p. 423)

The author, John Dickie, is Professor of Italian Studies at University College London. His previous works have included books about the Italian mafia, which perhaps explains the dominance of Italy, and especially Naples, in this book. I was frustrated by frequent allusions to “the leading historian of ….” without actually naming them, and the lack of footnotes was deplorable, replaced instead by an alphabetical list of references for each chapter at the end making any further reference impossible. He acknowledges that this is a “poor substitute”. He’s right.

Despite the decline in numbers and wealth, I’m not sure that Freemasonry (or some other variation thereof) is completely finished, given the rise of conspiracy thinking, polarized politics and the attempt by some on the right to return to some lost golden age of patriarchal and ordered society. Rather more positively, Dickie closes by suggesting that:

Even those of us who would never dream of being initiated can find lessons to learn by viewing history through a Masonic lens. Globalization and the Internet are forcing us to rethink and reinvent a fundamental human need: community

p.432

My rating: 8/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

Read because: I heard the author on a podcast.