I’ve just returned from doing my democratic duty up at the local school. It’s election day here in Australia, and one that I feel rather pessimistic about. Elections are always held on a Saturday and voting is compulsory- something that I have absolutely no problem with. I think of the bravery of people in other parts of the world who carry around their ink-dipped fingers (how dangerous could that be in some situations!) and I am grateful that I can vote in a country that expects and requires me to do so as a citizen in a well-organized and fully-financed electoral system. My gratitude and trust in the system stands, no matter what the outcome tonight, tomorrow or maybe weeks down the track.

So what about elections in Judge Willis’ time? Of course, the whole concept of a Federal Election in Melbourne had to wait until 30 March 1901 but the first colony-wide election for NSW was held in 1843. Until the passing of the 1842 New South Wales Act, the Legislative Council had been nominated by the governor, but the 1842 Act allowed for 36 members, twelve appointed and the rest elected. The relative lateness of elected representation reflects the penal origins of the colony: Upper Canada had been awarded representative government nearly fifty years early with the Constitutional Act of 1791.

Port Phillip was still part of New South Wales at this stage. Six members in total would be elected from the Port Phillip district, five from the district as a whole, with one from Melbourne. There was not exactly a rush: the Council sat in Sydney, six hundred miles away, and few Port Phillip citizens were prepared to travel and stay in Sydney for council sessions. As a result, of the five district members who were elected, only two – Charles Ebden and Dr Thomson from Geelong- were from Port Phillip. The rest were Sydney-siders: Dr Charles Nicholson; the merchant Thomas Walker (who did have extensive holdings in Port Phillip and particularly in Heidelberg but was based in Sydney); and Rev John Dunmore Lang. Two other Sydney residents- Thomas Mitchell, the Surveyor General, and James Macarthur Jnr, the son of Hannibal Macarthur also stood, but Mitchell was not successful and Macarthur withdrew his nomination before election day. There had been talk earlier that Joseph Hawdon, the wealthy cattler overseer and builder of Banyule homestead in Heidelberg, would stand but this did not eventuate and he, too, was Sydney-based.

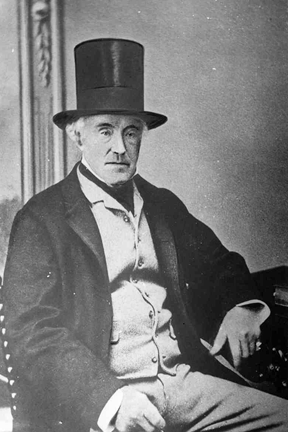

Certainly the election did not have the immediacy of the Town Council elections which had been conducted some six months earlier. Edward Curr, who had previously been a member of the Van Diemens Land Legislative Council, accepted candidacy for the Melbourne seat. He was a prickly, forthright character who clashed strongly with Willis, along with many others in Port Phillip, it must be said. It was his strong Catholicism that prompted the equally prickly and forthright Presbyterian candidate Rev J.D. Lang to cast about for a contending candidate for the Melbourne seat, lest Curr the Catholic be elected unopposed. Lang and Kerr, the editor of Fawkner’s Port Phillip Patriot (with whom Lang was staying while campaigning in Port Phillip) decided to approach Henry Condell, the Mayor, asking him to stand. They promised to organize a petition of 200 Melbourne electors by 4.00 pm the next day and Lang offered to write all of Condell’s speeches for him.

Once Condell had been persuaded to stand, an element of sectarianism was introduced into the campaign in a town which had, until that point, seen the denominations generally co-operating with each other, although this was being affected also by the changing demographic makeup of immigrants into the colony. Curr and his letter-writing supporter Alexander McKillop certainly saw the contest in these terms, as did Lang himself. And it is into this contest between Condell and Curr that we see Willis intervening in a way that even today raises eyebrows, just as it did at the time:

Alston's corner, cnr. Elizabeth St and Collins St today, the site of Willis' shop-bench encounter over the Curr/Condell contest

As a climax to these indecencies, the Resident Judge (Willis) dishonoured the ermine of his high office by requesting the retailers, with whom he did business, to vote for Condell; and one day, whilst on a vote-touting expedition Willis and Curr met face to face in the shop of Mr Charles Williamson, a Collins Street draper (lately Alston and Brown’s) where the Judge waxed so personally offensive that Curr’s forbearance only prevented the public scandal of a pugilistic encounter between the judicial canvasser and the candidate.” p. 333

The election was conducted in four locations. Voting for the district seats took place in Portland, Geelong and Melbourne, while the voting for the Melbourne seat took place in the Gipps ward of Melbourne. In many regards they were typical English-style elections: the votes themselves were announced (no secret voting here!), there were placards and ribbons, and the alcohol flowed freely.

The voting went off well enough until the polls closed at about 4.00 pm. Once it was clear that Curr had been defeated, his Irish Catholic supporters moved to the Golden Fleece Hotel where they hoped to find Condell, then to the main polling site at the Mechanics Institute in Collins Street where the results were to be announced. The Chief Magistrate Major St John and Dana, Chief of the Native Police arrived on horseback , and in the midst of brawling, the Riot Act was read. Forming groups of 50-100, the crowds broke up and raged through Little Collins, Collins and Elizabeth Streets with stones and brickbats. The military arrived, charged the mob with bayonets; hotels were closed and the mounted police patrolled the town. However, unlike Sydney where similar riots occurred resulting in the death of one man, there was no loss of life. A couple of days later, once the results had been collected from Portland and Geelong, the successful candidates were announced. The Port Phillip Herald 27/06/43 reported:

At the close of the ceremony, Mr Ebden’s horses were taken from his carriage, which containing Mr Ebden, his brother Mr Alfred Ebden, Mr Curr and Mr Foster, was dragged through the town. The town band paraded the streets from an early hour in the morning til late in the afternoon, but little interest was manifested in the proceedings, the dismissal of the judge having evidently taken possession of the public mind.

And here two of the anxieties that La Trobe dreaded coincided: the unruliness of the election, and the excitement over Willis’ dismissal. But that’s a post for another day (maybe).

It’s hard to tell how many people were eligible to vote. The franchise was for males over 21 who owned freehold property worth 200 pound or rented a property worth 20 pounds per annum, a natural born (British) subject or naturalized. Those who had committed “treason, felony or infamous offence” could not vote unless they had been pardoned or undergone their sentence- an issue of controversy in regard to the applicability of English law in a former penal colony. As far as the ‘district’ elections were concerned, the Port Phillip Herald a few days later published full details of the results. The names of the voters were given, the booth they voted at, the time that they attended, and the candidates to whom they gave their votes – no privacy here! The final results were: Ebden 228, Walker 217, Nicholson 205, Thomson 1843, Lang 165 and Mitchell 157 . In Melbourne, Condell received 205 votes to Curr’s 174 but the names of the voters were not given. I’m not sure how many votes people had, given that many men owned multiple properties, and how the practice of ‘plumping’ (i.e. giving all your votes to one candidate) applied here. Either way- we’re not looking at a huge electorate.

For myself, I would gladly drag a carriage with my first female prime minister through the town with the town band playing but I don’t know if that’s going to happen…

References:

M. M. H. Thompson The Seeds of Democracy, NSW, The Federation Press, 2006

A. G. L. Shaw A History of the Port Phillip District: Victoria before Separation Carlton Vic., Melbourne University Press, 2003

Jennifer Gerrand ‘The Multicultural Values of the Melbourne 1843 Rioting Irish Catholic Australians‘ Journal of Historical and European Studies, Vol 1 Dec 2007