As I remember, it was in about Grade 5 that we “did” Australian history – the first taste of ‘aborigines, explorers, gold and Eureka’- and we used a plastic template to draw Australia. Poor old Tasmania didn’t even get a look-in, but I was also disconcerted by the borders of Victoria, which started with off the solid line of the Murray River before trailing off into dotted lines, like the other state boundaries. Not that the dotted lines were any use: they were impossible to fit a pencil point into, anyway, but they did give a visual sense of state borders. (And emphasized the importance of water compared to boundaries, even though that water might disappear completely from time to time).

Australians are not unaware of surveyors in their history. Travelling around South Eastern Australia, one often encounters the ‘Major Mitchell Trail’, or markers of the trail of Hume and Hovell, more often described as ‘explorers’ but at early stages of Australia’s colonization, the distinction was perhaps less clear cut. Many Australians are aware of Goyder’s Line that separates arable from drought land in South Australia, and the final proclamation of the Black-Allan line in 2006, more than 130 years after it was surveyed, brought the names of surveyors Alexander Black and Alexander Allan to (somewhat) public notice. But I must confess that I had never heard of Thomas Scott Townsend, the subject of this biography, although his name was given to the second-highest mountain in Australia and Townsend Corner marks where that solid line dissolved onto dots on my plastic school template. The author of this book, Peter Crowley, felt that Townsend had been short-changed:

As far as I am aware, this is the first biography dedicated to Townsend, a man who was the pre-eminent field surveyor of the south-east during the squatter age…I felt for Townsend and his family and wanted to restore his memory to the place it deserved. His triumphs and his travails were of compelling human interest, a tale of suffering and sacrifice endured in service to the public, and they were always going to be the backbone of this narrative. (p.18)

Narratively, Crowley gets you in from the outset. He starts with a suicide in 1869, more than twenty years after most of the action in this story, when the reclusive and belligerent Townsend kills himself by cutting his own throat. What could have led to this “pre-eminent field surveyor” taking his own life?

Thomas Scott Townsend was born in England in 1812. He, along with his parents and 10 siblings, lived at Woodend House in Buckingham Shire. His older brother Joseph was apprenticed to a land surveyor and then began his own surveying business, and it was later noted by Major Thomas Mitchell, the explorer and Surveyor General of New South Wales that Thomas Townsend had been “bred in a surveyor’s office in England”. Thomas had arrived in NSW at the age of 17, and after being unable to find employment, was the recipient of a recommendation to the Surveyor-General from the MP for Oxfordshire, generated no doubt as part of the lobbying and patronage network which underpinned colonial mobility around the empire. He was initially appointed as a draftsman in a temporary capacity in 1831, but remained an employee of the survey department for over 20 years. Those same patronage networks, deployed to the advantage of other new arrivals, were to stall his progress up the career ladder when other aspirants were appointed over him on the basis of similar recommendations from ‘home’. He had to wait under 1845 to be promoted to the position of ‘surveyor’ and the highest position he reached was Acting Deputy Surveyor General of New South Wales.

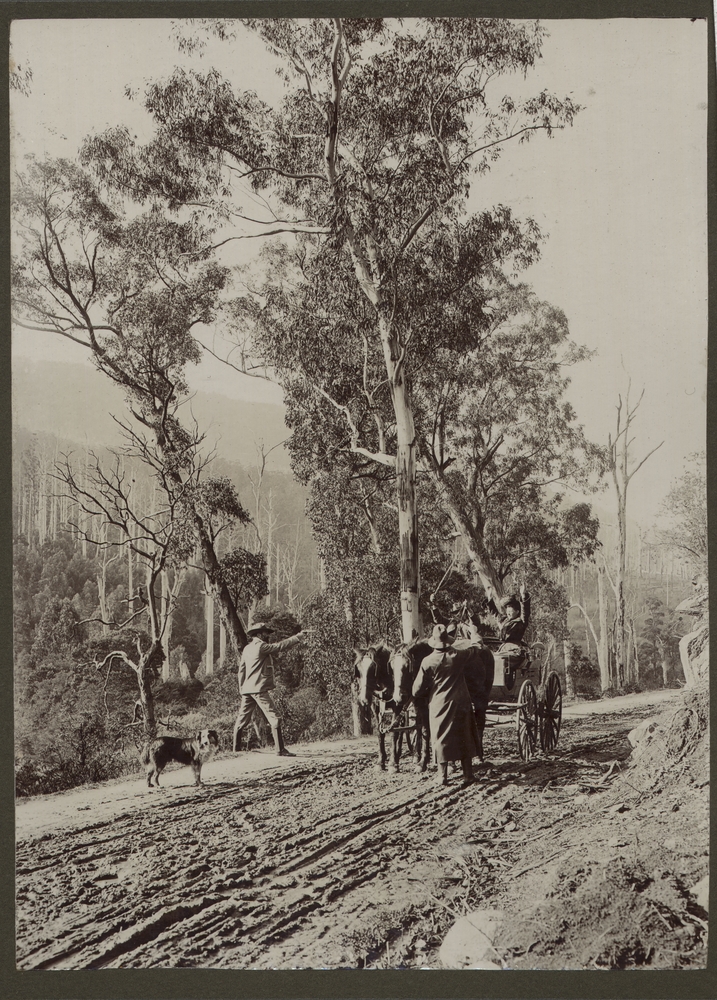

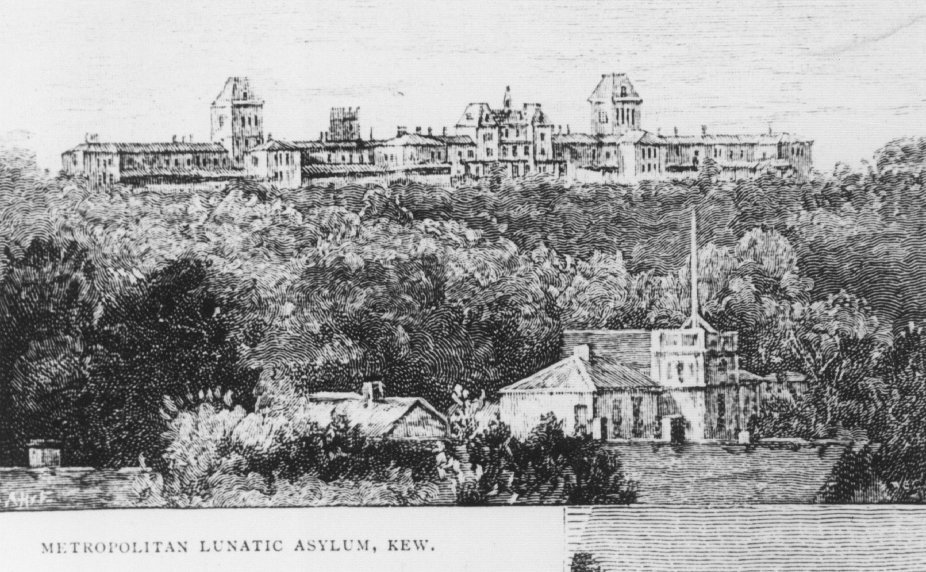

In these twenty years he was appointed to various projects: laying out towns in Albury, Geelong, Eden; acting as Surveyor-in-Charge of the Port Phillip District; surveying coasts in Gippsland and the South Coast; ascertaining the source of the Murray River; and traversing the Main Range of the Snowy Mountains, making an ascent of the then-unnamed Mt Kosciuszko. Even though the Surveyor-General, Major (Sir) Thomas Mitchell, was able to inveigle long periods of leave for himself to return ‘home’, it seemed that each time the opportunity for a voyage or desired excursion arose, the government found Townsend indispensable and directed him to another suddenly-urgent project. Located far from Sydney and beyond the reach of official orders, he devised his own surveying activities as well, using the time when snow and floodwaters made surveying impossible to go back over areas that had been surveyed in haste earlier. He was ridden hard by the government, but he was a self-driven man as well : perhaps there is a streak of madness in all explorers and surveyors? He was not the first man to enter these areas – he found that squatters had preceded him nearly everywhere he went, following generations-old indigenous paths to find open pastures – but the methodical, documented act of surveying was a form of exploration in its own right.

Surveying involved long periods living in tents in the bush, unless the territory was so impenetrable that supplies had to be left with the oxen and horses so that the surveying party could move unencumbered, sleeping in the open at night – surely a daunting prospect in south-east Gippsland and in the Great Dividing Range. Surveyors used the ‘chain and compass’ method, using a Gunter’s chain to measure distance and taking bearings and angles with a compass. Sometimes they had access to a circumferentor, a compass mounted on a tripod with a sighting arm, or later a theodolite to measure angles. They recorded information in field books, from which they later plotted their data onto maps. At this stage they did not use contour lines, but instead depicted ridges, spurs and valleys by parallel lines known as hachures. Thus, those early maps look quite different to the contour maps we are accustomed to today, and certainly they have their own beauty.

Townsend was instructed to record the indigenous names for the geographical features he surveyed, even though those other names were later overlaid by British names awarded as an act of homage to patrons at ‘home’. Crowley emphasizes throughout the presence of indigenous clans and nations across the whole area that Townsend surveyed. Indigenous guides could easily be procured from squatting stations, and Charley Tarra (or Tara) was a member of several surveying parties. Crowley notes the massacres associated with various squatters, although he does not interrogate the role of the surveyor in a political and legal sense. Certainly guns and violence led to appropriation of the land on-the-spot by the squatters, but it was the legal act of survey and resultant gazetting that imposed British title and sovereignty over Aboriginal land.

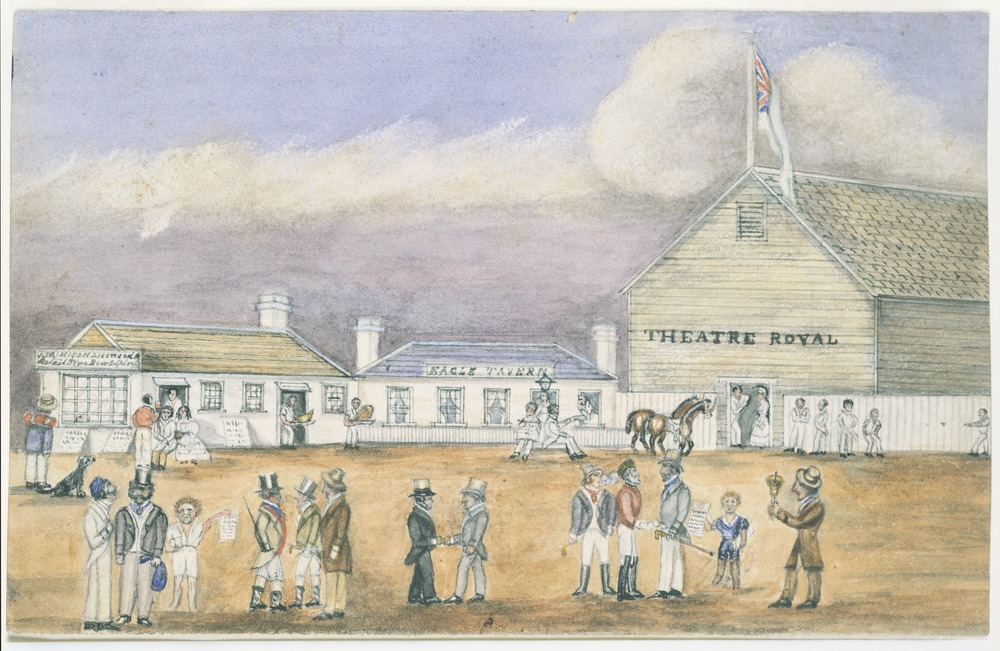

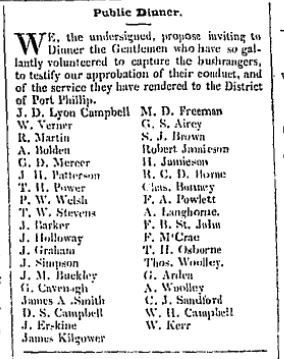

Townsend’s work was directly impacted by colonial politics. When he first arrived, the NSW government had already lost control of the squatters outside the Nineteen Counties, and pastoralists were moving into the Port Phillip district from across Bass Strait. When he arrived in Port Phillip as Surveyor-in-Charge, there was already a large backlog of work awaiting him, which only increased further with the influx of population during the gold rush. With the cessation of transportation, the source of cheap surveying teams dried up, and it became difficult to find men prepared to face the isolation and sheer hard work of the task. Squatting regulations introduced a degree of urgency into surveying work, with the imperative to mark out town reservations close to water supplies, to avoid them being swallowed up into large estates. Separation in 1851 brought politics into surveying, with suggestions of a border on the Murrumbidgee which would have placed the Riverina and the later Canberra district within Victoria. Townsend had his own opinion about where the boundary should be, suggesting that instead of rivers being used (which can, after all, expand and shrink depending on climate), mountain ridges and port access should guide the decision.

Crowley depicts well the arduousness of surveying work. It seems that Townsend suffered more from the heat of surveying the Murrumbidgee than he did the snowdrifts and dankness of the south-east. Men could get lost just when stopping aside to relieve themselves; sometimes ticket-of-leave and convict team members were unruly or absconded; and the sad death of Major Mitchell’s son 18 year old son Murray, who accompanied Townsend on his survey of the lower Snowy River, highlighted the isolation and dearth of medical assistance out on the field.

The isolation, the incessant work and the rootlessness of surveying work over such a long period of work did not augur well for a desk-bound job in Sydney once Townsend finally achieved the promotion he craved. In fact, he was quite clear with the governor that he felt that he still needed to be in the field to ensure the accuracy of the surveys conducted by men under his supervision. He married, but seemed unsettled and increasingly paranoid about his wife’s fidelity and sure that he was being ‘watched’. Many people were concerned about him, and felt that a trip back ‘home’, which had been postponed for so many years might alleviate his mental distress. This was not to be… and here we are back at the start of the story, with Townsend’s suicide. I had felt at the start of the book that Crowley had laboured the ‘ignored hero’ point a bit, but by the end, I no longer felt that way. Townsend has been overlooked. Strezlecki has garnered most of the praise for his exploration of the Great Dividing Range, and Alexanders Black and Allen received acknowledgement for tracing the Murray River that Townsend had surveyed twenty years earlier.

Crowley tells the story well, interweaving the biographical with the historical. He draws on official correspondence between Townsend and his colleagues and superiors, Colonial Office files with and about Townsend (which reflect the usual aggrieved tone of correspondents and pompous tone of Colonial Office officials), Townsend’s maps and drawings, and in quite a coup, family correspondence that fills in the last years of Townsend’s life. At times, particularly at the start of the book, I felt that he was distracted by the weeds a bit, giving more context and background information than was necessary. The book does not have an index, which would have been appreciated, but the old fashioned chapter summaries at the start of each chapter helped you to locate information. There was a single list of footnotes that spanned across all chapters. The book did seem to take an inordinately long time to get started, with a note about measurements, geographical notes about what constituted the Great Dividing Range, or the Murray River, a cast of characters, a timeline, acknowledgments and an introduction- all before we get to chapter one. Much of this could have gone at the end of the book.

The one thing that I cannot understand, however, is the dearth of clear, modern maps in this book. With the National Library of Australia as publisher, use of historic maps and documents is to be expected but they were virtually illegible once reduced in size and rendered into grayscale. For much of the book I had no idea where Townsend was or where he was going and no sense of distance or remoteness. This was a book that cried out for a visual representation of land: something to which Townsend devoted his whole life.

But these are quibbles about decisions that may well have been beyond the author’s control. Crowley captures well the incessant demands of the work, the beauty and intimidation of the lands he was surveying, and Townsend’s inexorable spiral into mania. It is both a very human story, and yet one placed within the vastness of unsurveyed territory. Townsend may have had to have wait more than 150 years for his biographer, but with Crowley’s book he receives the recognition earned and withheld for so many years.

Sourced from: review copy from Scott Eathorne, Quickmark Media

I have included this book in the

I have included this book in the

I have posted this review to the

I have posted this review to the