This morning’s Age newspaper brought with it a supplement sponsored by Melbourne University called “Voice”. I’m usually rather sniffy about this supplement, which feels like a long advertisement for the Melbourne Model, but I must admit that I do take a peek at it nonetheless. Interestingly enough, pages 3, 5 and 7 identify the supplement as an ‘Advertising Feature’, but this is not apparent on the first page. This particular edition is all rather reflexive: a supplement of the newspaper devoted in this edition to predictions about the death of the newspaper; a supplement called “Voice” that is print-based; mirrors upon mirrors upon mirrors.

I was interested by an article ‘NEWspaper Business Model’ by Joshua Gans , Professor of Management (Information Economics) at Melbourne Business School. In an article reflecting on the business imperatives that militate against the ‘old’ newspaper business model, he notes the inflexibility of publishing deadlines for the conventional newspaper, and the effect of loss of timeliness in an immediate, socially-connected online environment. He makes the comment:

The conventional view about the news is that it is ‘information’ or ‘content’. People value knowing what is going on. But this fails to recognise that as content, the news is fairly inconsequential…Put simply, for the vast majority of news, the value comes from being able to talk about and share it (“did you hear about?”) rather than add to your pool of knowledge per se. And this is precisely why the loss of timeliness is so critical.

Thinking about the Port Phillip newspapers, I think that this has always been the case. Melbourne’s first newspaper, John Fawkner’s Melbourne Advertiser was hand-written and largely filled with shipping news, cut-and-paste from Sydney papers and advertising for local businesses – especially Fawkner’s own! (click here for images and transcripts of the first editions). However, much as Gans suggests here, the importance of the paper lay not in the content, but the fact that people talked about it, and Fawkner initially planned to give the paper away for free. But never one to let a business opportunity pass him by, he began including the paper in the cost of a counter meal at his pub.

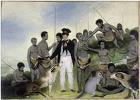

By the time that Judge Willis arrived in Port Phillip, there were three regular newspapers, each published twice a week: the Port Phillip Gazette, edited by the very young George Arden (in fact, it never fails to strike me how much Port Phillip was a young-man’s sort of place); the Port Phillip Herald, edited by George Cavenagh; and the later incarnation of the Melbourne Advertiser, John Fawkner’s Port Phillip Patriot. Newspaper editors were prominent in civic affairs and they had a vested business interest in stimulating passions over local politics and events. Their newspapers reflected the political stance and interests of their editors, and in Judge Willis’ case, the editors and their relationship with the Judge often was the news. Each newspaper appeared on a different day, giving six-day-a-week coverage, but without directly competing with each other by appearing simultaneously. On momentous occasions- for example, Governor Gipps’ visit, the newspapers co-operated to publish a common supplement. Not that all was sweetness and light by any means: many column inches were devoted to slanging off at each other’s accuracy, print quality and personal qualities of their respective editors. Underneath all this largely confected piss-and-vinegar was a fundamental political split between Arden and Cavenagh on the one hand, and Fawkner on the other. The controversy over Judge Willis fed directly into and reflected this political factional split.

The nature of timeliness- as commented on in the Gans article- is instructive here. The newspapers themselves seem to have a very limited time-scape at the local level, possibly because there was a three day gap between editions of any one paper. Events were generally advertised only about a week in advance, and reports of events after the fact tended to only look back a couple of days. For example, meetings were advertised that would occur that day, or in the next couple of days; and court reports might extend backwards perhaps four or five days but not much further than that.

Juxtaposed against the limited time-frame of local events is the long gaps between intelligence received from other colonies and especially from overseas. The newspapers often listed the dates of the most recent newspapers received as ships docked, and all three newspapers would comb through for news articles that would then be presented as if they had just occurred, although of course, they were some four or five months outdated. But for the people of Port Phillip, they were literally ‘news’ as no-one else had any more recent intelligence, and very much the stuff of “Did you hear about?” conversations.

The National Library of Australia has a fantastic site for colonial newspapers, although the early newspapers of Port Phillip do not yet appear (nor do there seem to be any plans for them to do so in the next 3 years) , with only the Argus from 1846 represented- too late for Judge Willis. However, just as the Port Phillip papers cut and pasted extracts from the newspapers of other colonies, the action was reciprocated and extracts from the Port Phillip Gazette, Herald and Patriot often appear in other newspapers, albeit some weeks after the original publication.

If you look at other newspapers published at the time (e.g. Hobart’s Courier, Town Gazette; the Maitland Mercury; the Perth Gazette and the Sydney Gazette), you’ll notice a similarity between them in layout and structure. For the Port Phillip Herald which, until recently was available at Paper of Record but has since been swallowed up without trace by the Google juggernaut, it might be interesting to do a content analysis on a few 1840s editions.

Tuesday 13 July 1841 (168 years ago today)

Page 1

Page 1 consists entirely of advertisements. The only illustration is a picture of a ship which occurs against a number of the shipping advertisements- a stock icon that is identical in each case. There are eight advertisements for ships soon to depart (1 for London; 2 for Hobart, 1 for Port Albert (Gippsland) and Launceston; 1 for Launceston direct; 1 for Adelaide, 1 for Port Nicholson New Zealand, and one to ship goods up from Hobsons Bay). Six advertisements refer to goods recently landed and 1 refers to a tobacco shipment. There are 9 real estate advertisements, 1 for a demountable house and 2 for tents. There are 13 advertisements for stock (cattle, sheep and pigs); 3 for seed crops; and 2 for horse sales. There is an advertisement for the sale of a carriage ; a printing press (the Herald’s very own!), surgical instruments, a piano and a billiard table. There are retail advertisements for 2 butchers, 1 chemist, 3 grocery warehouses, 1 coachbuilder, 1 hairdresser, 2 cloth warehouses, and 1 saddler. Four hotels advertise their services; there are 2 advertisements for accountant/attorneys and 1 for an agent. Two banks and one insurance agency advertise; and there are three advertisements for ladies’ seminaries (but not boys’ schools). There is one advertisement for the upcoming races, and one for a subscription concert, complete with a list of the men who have already purchased their tickets.

Page 2

Page 2 and 3 generally constitute the local news- the “Did you hear about?” component of the paper. The top of the first column is always dedicated to Shipping Intelligence, with a list of the ships due to arrive and depart. This is followed by Commercial Intelligence, which brings market news from Hobart, the Cape of Good Hope (extracted from the South African Advertiser of May 5), and Melbourne auction sales of merchandise, property sales and sheep prices. Then appears a Calendar, showing the moon’s age, sunrise and sunset and tide times for high water in Hobson’s Bay- reminding us of the importance of night in a colony with only very rudimentary street lighting outside public house and otherwise reliant on moonlight. Further on this page there is a call for lamps to be hung near the ditches that run beside the main intersections.

The dates of the most recent newspapers received are then listed, and this emphasizes the variation of currency of overseas intelligence: England 10 March; China 23 March; America 17 February; Sydney 26 June; Van Diemen’s Land 1st July; South Australia 9 June.

Then follows a bit of inter-newspaper squabbling over circulation figures- a newspaper habit that seems to persist until today with the Age and Herald Sun always BOTH managing to draw comfort from recent circulation figures in 2009. There is another dig at the Patriot’s inaccuracy further in on this page, in relation to the War with China.

The Editorial for this issue has two topics: first, a call for Gipps to consider the figures in the Abstract of Colonial Revenue which demonstrate the wealth being siphoned off from Port Phillip, without any reciprocal expenditure; and the need to fix the prices charged by Carters.

The Domestic Intelligence section lists the auctions scheduled for today, tomorrow and Thursday. There is a long report of the Coal Company meeting with the resolutions listed. There is a call for more punts, government-funded hospital conveyance, and a complaint about rubbish and effluvia in the streets, and the failure of the church doors to properly close out the sound of the street outside. Mr Gautrot’s benefit concert (advertised on p. 1) is publicized, and there is a cautionary tale about the drunkenness of an old army pensioner who ended up falling into the Salt Water Creek. There is a humourous and evocative word-picture of a steamer departing from Queen’s Wharf, and a commentary on under-age children giving the oath in the courts. The Commissioner of Crown Lands now has a drop-box for documents, and St John is mentioned as a candidate for the Police Magistrate position. There is also a vacancy for Chief Constable, as well as a criticism of the behaviour of other police constables. A bag of ginger that must have dropped from a dray now rests at the police office. The pastoral and farming nature of the colony is emphasized by an article encouraging people to feed maize to their horses, the danger of infected scabby sheep, and the habit of hiding stolen cattle in the bush then claiming the reward for their return. There are street dangers from runaway horses, four cases of burglary, a murder on the Sydney Road, a drowning on the Goulburn River, and the death by burning of a man so intoxicated that he fell into the fire. The construction of the new jail is progressing well; a Sabbath Observance petition is in circulation; there is talk of the purchase of a second steamer for Hobson’s Bay; there is a creditors meeting for Langhorne Brothers and fall-out from the windup of the Pastoral Society. The military escort accompanying La Trobe and Lonsdale back from church is berated for smoking cigars in public.

Page 3

The court and police reports are often found on p.2 or 3. This issue has notice of the upcoming criminal hearings on 15th, two reports of the coroner’s inquests (both deaths caused by excessive drinking), and a daily report of Police Intelligence. The Police Intelligence column, which often culminates in a hearing before the magistrates or with the perpetrators cooling their heels in the lockup is written in a jovial, Pickwick Papers-esque style. The Original Correspondence consists of two letters to the editors: one from “A Settler on the Plenty” complaining about the erection of fences across what had until recently been public thoroughfares, and a letter from “Justicia” arguing that there are no avenues for appeal against the findings of the Court of Quarter Sessions. There is one personal classified, advising of a marriage. The paid advertisements then continue from Page 1, with 2 shipping advertisements, five positions vacant and six positions wanted advertisement, 10 real estate to let advertisement, 3 lists of stock available in trading houses, 13 auction notices for property, stock and china sales. The Sabbath Day Observance petition is printed, along with arrangements for signing it, and there are other small notices e.g. tenders to build the Roman Catholic Church, stolen horses; notices from the Navigation Company and the Port Phillip Bank etc.

Page 4

The top left hand column of the Port Phillip Herald is usually reserved for poetry- in this case “Oh! I remember well”- author unknown. Then follows extracts from other newspapers: in this case, from Van Diemens Land (which includes some news from Madras); Sydney extracts, and about 3 columns of English Extracts. For the predominantly British settlers in Port Phillip, no doubt the English Extracts held strong “Did you hear that..?” appeal. So what sort of information was extracted? There’s a long report of the English and Turks fighting the Bedouins in Gaza; information about settling the Danish claims; fires in Bermondsey, a robbery in Liverpool, a duel in Regents Park, the defalcation of one of the Dublin Board of Aldermen, a horse accident involving the Hon. Mr Dundas the M.P. for York, George Stephenson the engineer’s purchase of coal mines and the presentation of plate to Rev T. Dale, late Professor of English Literature and Modern History at Kings College London.

A half-column of Miscellaneous Extracts includes a piece from the United Service Gazette about Commodore Napier; and a list of moral virtues drawn up by Dr Franklin for the regulation of his life- temperance, silence, order, resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, cleanliness, tranquility and humility.

Then follows more paid advertising- 13 ‘to let’ advertisements, two board and lodging advertisements, a string of lost, found or strayed advertisements for stock (offering up to 20 pounds reward for a bullock) with one advertisement for the return of George Williams who had engaged as a servant but absconded (offering only 2 pounds reward). Four creditors meetings; one legal notice, two change of trading address, 1 dissolution of partnership. The final column is always devoted to Wholesale Prices Current for imported and local produce, then subscriber and advertiser information and the name of the editor and printer.

So two years later, did the papers look the same? By this time, Port Phillip had been gripped by economic crises, and the Legislative Council elections and Town Council elections had been held. Judge Willis had just returned to England, so that particular controversy should be in abeyance. I actually started looking at March 1843 to avoid these events, but found myself wondering if seasonal events were influencing the content so have settled for a similar date, two years on.

Friday 14th July 1843

p. 1

Only one ship, bound for Sydney. A large advertisement for the Australian Colonial and General Life Assurance Company, and small advertisements for a butcher, umbrella seller, wine and spirits. The silk dyer and scourer has reduced his prices because of the depression; a registry office for servants has opened, and there is one position wanted advertisement. Two houses to let, one house for sale, one farm. One ladies seminary. There’s quite a bit of official Government advertising- a long column authorized by Gipps proclaiming the boundaries of the Port Phillip district, deeds of (land?) grants arranged alphabetically, depasturing licences. There’s a list of eight men who had absconded from the government stockade, along with descriptions (Thomas Taylor, age 30; native place Liverpool; trade or calling, sailor; when tried April 1836; sentence, life; ship, John; year of arrival 1837; height 5 feet 6 inches; complexion, ruddy; hair, brown; eyes, grey. Marks, woman and flag anchor, F. O. seven stars on right arm, and weeping willow on left arm). Actually- they’re all quite short- the tallest is five feet 10 inches; the shortest 5 ft 3. There’s official notification of the opening of the post office at Port Fairy. There’s a column of stock impounded at the South Yarra Pound. The Wholesale Price Current list has moved onto the front page in this issue.

p. 2

The shipping news remains at the top left column of Page 2. There is an advertisement for a special opening of the theatre for a performance of ‘Frederick the Great’ , followed by singing and dancing, and the favourite melodrama ‘The Bandit Merchant or the Dumb Girl of Genoa’.

The editorial greets the arrival of Judge Willis’ replacement Justice Jeffcott. From Sydney comes the results of the Legislative Council elections. Four and a half columns follow with details of the Town Council proceedings from Tuesday.

The Domestic Intelligence column includes information about the anti-Willis petition (which the Herald championed); the thwarted escape of two convicts en route to Sydney; notice of scabby sheep; criticism of the Town Clerk for accompanying Judge Willis to the boat for his return home; a sentence of flogging for theft.

p. 3

As with the 1841 paper, the third page maintained its focus on court and police matters. Of course, the Supreme Court was in abeyance because of Judge Willis’ amoval, and half of the first column reports on the address to Judge Willis by some of his supporters. There is then a long report about a summons issued at the Police Office over Capt S. J. Browne (the father of the writer Rolf Boldrewood) and his attempt to take property back to England on the same ship that Judge Willis was to sail on. There is a short report on the Court of Petty Sessions, and notice of the next sitting of the Court of Requests. Police reports include arrests for prostitution, insolence and neglect of duty by the assistant executioner at the jail, and forgery. A Fred Ebsworth of Pitt Street writes to the editor in the Original Correspondence column regarding the boiling down of sheep (a process that stopped the free-fall in sheep prices in the province). A Government proclamation issued under the auspices of Governor Gipps marks the August meeting of the Legislative Council in Sydney.

Paid advertising follows- 2 ‘to let’ advertisements, one farming allotment sale, an offer of indenture of two respectable young men as druggists. There are auction sales for building materials, carpet, clothing, tea, ironmongery, coffee and clothes, and four stock sales. There is a long list of the library books being auctioned by a gentleman about to leave the province- on the Glenbervie with Judge Willis perhaps? Willis himself- although there’s a large number of theological works in the collection. Current events include meetings of the Port Phillip Bank and shareholders meeting for the Port Phillip Steam Navigation Company, notification of the cancellation of a lecture at the Mechanics Institute and the second anniversary of the opening of the Wesleyan Chapel. It is striking and telling that there are four insolvents’ sales- something not seen as prominently in 1841.

p. 4

Two rather paradoxical themes take up the final page of the paper. One is the aerial ship, and a long extract from the Sydney Morning Herald of June 28th praises the technological change experienced so far- railways, gas lighting- and heralds developments in aerial navigation, with an aerial carriage raised and driven by a 14 horsepower steam engine. Other extracts from the Sydney Morning Herald include a list of new insolvents, and a report of the 28th Regiment in India.

The aerial ship is taken up in the English Extracts. The carriage is to be constructed of thin copper sheaths, with a boiler and two high pressure engines, and wings. A similar report is taken from the Calcutta Englishman.

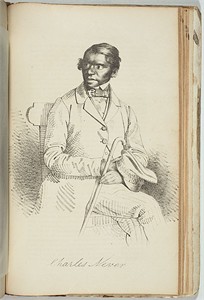

Rather more prosaically, there is a continuation from Chambers Information for the People No 79 titled ‘Sheep: Choice of Breeds’ that takes up nearly three columns and is to be continued. The identifying information at the bottom of the paper lists the printer and publisher of the Port Phillip Herald as Charles Fyshe.

So, where am I going with this? I don’t know! The local papers provide probably a higher proportion of international news than our newspapers today would, and much of this content is conversation-provoking gossip from home, or technology-based ‘next new thing’ ideas. There’s not a large ‘What’s On’ emphasis, especially in 1843. By 1843 there is much more emphasis on formal political structures like the Town Council and Legislative Council in Sydney. The small business ethos of traders and entrepreneurs seems to have dropped away by 1843, and the shadow of insolvency falls over the paper.

But in terms of “Did you hear about…?” the Port Phillip papers operate just as well as papers today do. A winning formula, you might say.