I seem to have missed the anniversary for Judge Willis’ departure from Port Phillip. After all, where else to start but at the end? It hasn’t just been inattention though: Behan (unreliable fellow that he is) dates the departure as the 18th July 1843 (Behan p. 285); The Patriot (13 July) dates his departure as that day; while the Gazette and Herald list the Glenbervie ‘clearing out’ on the 12th and ‘sailing’ on the 14th. I’m not really sure what the distinction is between the two terms: I assume that ‘clearing out’ involves moving from moorings in Hobson’s Bay while perhaps ‘sailing’ denotes passing the Heads?

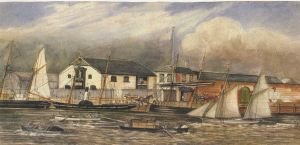

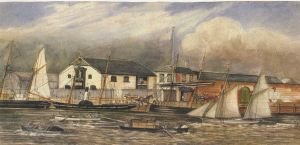

Nonetheless, it seems that on a wintry mid-July day, a crowd of people stood at the wharf, watching Judge Willis board the paddle steamer Vesta to be taken out to the barque Glenbervie anchored further out in the bay, headed for Valparaiso and home. I can assume that they left from Coles’ Wharf.

Coles Wharf was constructed between William and Queen Street by George Ward Cole (who later married into the McCrae family)in 1841 along the banks of the Yarra by building on sunken ships’ hulls (www.portaustralia.com/port-melb.htm) . At the time, the Yarra was bisected by falls roughly at the bottom of Queen Street. Above the Falls was fresh water- crucial to the small village, and below the Falls was saltwater. The maintenance of the falls to separate freshwater from saltwater was of vital importance initially, even though the presence of this chain of rocks across the river prevented ships from traveling further upstream. Much time and attention was to maintaining the Falls but by 1880 they were finally removed as part of river engineering works.

Here’s a description of Coles Wharf from The Times 22nd August 1853 that is perhaps a little less glowing than Liardet’s picture above.

There are two landing-places, and the steamers stop at the worst, called Cole’s Wharf. An enormous amount of traffic has certainly been thrown suddenly upon this spot; but, considering the revenue derived from it by the proprietors, something might have been done to redeem it from being, as it is, a disgrace and scandal to the city. Goods are tumbled on to the bank, and the drays back up to them to be loaded through pools of black mud, in which they stand nearly axle-deep. Boxes, cases, and bags (no matter what their contents) may roll into the slush, and stay there soaking till called for. Expensive as horseflesh is, half the power of the animals is wasted in getting out of these pits and the deep ruts of the roadway, which a few loads of stones would fill and level. There is no shed to protect goods liable to be damaged by rain. Reckless indifference to everything but collecting the enormously high freights up the river, and the still higher rate of carriage to the city, seems to be the rule. Combined, these charges have frequently amounted to more, for a distance of six or seven miles, than the freight of the goods from England. The other landing-place, the Queen’s Wharf, is a little higher up the river, and here the accommodation is much superior, a proof that improving is not so impossible as represented.

I stood where the wharf was today. It’s hard to picture it. The smell of chip oil is too strong as it wafts from Flinders Street Station and the roar of the traffic is a constant background noise. I’m sure that the air must have been saltier and tinged with wood smoke from the paddle steamer. Perhaps it sounded like Echuca, with the steam whistles, the shouts while loading and unloading goods and the sound of horses’ hooves in the streets behind. The sky would have seemed bigger with no high-rise towers, and the green of the bush would have crept up to the river banks in places, or formed a backdrop against the horizon. But today, like then, there is a stiff breeze that blows across from the water.

The Port Phillip Patriot (13 July) announced:

THE LATE RESIDENT JUDGE

His Honor Judge Willis embarks for England today by the Glenbervie, and will probably leave this port in the course of tomorrow. A large number of our fellow townsmen have signified their wish to accompany his Honor or board, and the Vesta steamer, has in consequence been engaged, to convey the numbers who are desirous of joining in this last tribute of respect before his Honor’s departure from our shore, whence he carries with him the esteem and veneration of nine-tenths of the whole community.

The steamer will leave the wharf at eleven o’clock; it will be necessary, therefore, to be in attendance punctually at that hour.

And a couple of days later, The Port Phillip Gazette (15th July) reported:

On Thursday last, at 12 o’clock, His Honor Mr Justice Willis took his departure from Melbourne, in the Vesta, steamer, which had been specially engaged for the purpose. About four hundred of the inhabitants were in attendance at the Wharf to bid His Honor farewell. Several gentlemen accompanied His Honor down the river, and saw him on board the Glenbervie. A general gloom seemed to prevail on the Vesta heaving her moorings with our late talented and injured judge on board.

Who were those gentlemen, I wonder? I can’t imagine that any of the men who had signed the petitions against him would have been in attendance. Probably those men who had supported him throughout- Verner and the Boldens, perhaps Rev Alexander Thomson from St James? Were there manly handshakes, throat-clearings and fine sentiments expressed? Was there genuine pain, or did the bluster and bravado of injured feelings and outrage dominate?

Were their wives there, I wonder? Mrs Willis, who was to deliver her second child when the ship docked at Valpairaso- had she overcome the queasiness of morning sickness as the steamer throbbed towards the Glenbervie? What a tumultuous three weeks- their possessions were sold off in Heidelberg’s First Garage Sale, and they shifted into the Royal Hotel in Collins Street to make their final preparations. Did she have friends that she was leaving behind? When did they make their farewells? Like so much else of women’s experience in early Port Phillip, this is another male dominated performance. The women may have been there, but we just don’t know.

And what happened next, as the paddle steamer moved up along the river, out of sight with perhaps just a smudge of smoke to show that it had ever been there? Perhaps there was another round of cheers, but eventually the crowd would have to disperse, picking its way through the muddy Melbourne streets (Port Phillip Herald 18 July). And Judge Willis, his wife and child headed for home.