Well, I did it in 2012 and I’ll do it again in 2013. I’ll probably read quite a bit of fiction because I tend to anyway, but this year for the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2013, I want to concentrate on Australian Women Historians writing Australian History.

Last year Yvonne Perkins in her blog Stumbling Through the Past analysed the gender balance of book reviews in three major Australian history journals. She found that by and large, History Australia and Australian Historical Studies have a fairly even gender balance the books that are reviewed (with even a slight leaning towards female writers), while The Australian Journal of Politics and History had more reviews of male authors. It’s an interesting post- read it here– and it spurred her to develop a list of books written by women historians.

To be honest, I was surprised that there was such strong gender balance in two of the journals she analysed, because my perception is that more books are written by male historians. I did a little detective work myself, counting the books in the ‘Australian Studies/Australian History’ section of Readings bookstore in Carlton. Whatever the breakdown in the book review section of the major Australian historical journals, on the shelves male historians romped it in – only 28 of the 95 books I counted were written by women.

And certainly, if I turn my head to the left and look at my own bookshelves, there are many more books written by male historians. I can think of a number of reasons for that. First, I don’t very often buy history books new (whereas I do buy second-hand) and so any bias in the past will be reflected in the books I buy. I really am trying to have less clutter around, and so I borrow from the library, and try not to buy. But I’m often attracted to the remainder bin, the ‘Specials’ table and the second hand bookshop, and the piles of books that academics put outside their door when they’re cleaning up their offices…..and my bookshelves show the result.

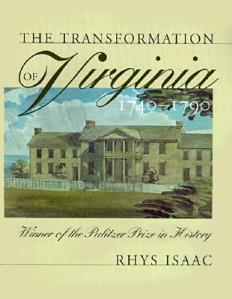

Second, my area of interest is nineteenth century colonial societies in white settler nations- especially Australia and Upper Canada. It’s a fairly old-fashioned sort of interest now, and was mined fairly heavily in the 1960s and 1970s. I’m coming to it imbued with all the ‘isms’ and ‘turns’ of the past fifty years, but I must admit that many of the books on my shelf are terribly dated- and the bias towards male authorship in the 60s and 70s shows.

Finally, and related to this, early women Australian historians writing Australian history had a hard time even being recognized as academics, let alone published academics. Some time ago, I wrote a post about Kathleen Fitzpatrick , a historian at Melbourne University who wrote, but abandoned, a book on Charles La Trobe that she had been working on for some time. There is a suggestion that she withdrew from the field because another (male) historian was writing on him as well, and she didn’t want to compete with him.

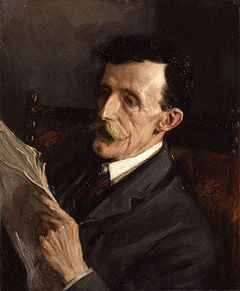

Just recently, I read an article called ‘ The Writing of Australian Biography’ by M. H. Ellis who is depicted in his Australian Dictionary of Biography entry as just the sort of male historian that one might want to step back from. It was published in Historical Studies (Vol 6, No. 24, May 1955) after being read before Section E of the Conference of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science held at Canberra in January 1954. I disagree with much of what he says in his paper, but what really struck me was the language. I’m sure that any female biographer with the audacity to even sit in the room slunk away quietly, well aware that she had no right to be there:

No very young writer, hastily scrambling over a rich reef of documentary material, is likely to have the natural insight to enable him to distill from it a living image that will appeal as being the stuff of life to readers of diverse ages and mental outlooks in different periods, and inspire confidence in any picture he may draw of the mind and motives of a man of mature years… Nothing but slow filtering of essentials through the sieve of parallel experience can teach one man what makes another man function and behave as he does and enable him to put his findings down on paper in a manner to convince those who have endured or are enduring life that he is setting down truth.”(p 434)

Or how about this one?

There must be in all true biographers a natural and honest bias toward good principles, which are the yardstick by which men are measured. Biographers should be the most human of men and subject to the decent prejudices and preferences which guide the ordinary citizen. It would be right against human nature if such men did not involuntarily exhibit their likes and dislikes, their amusement or lack of amusement, their approval or disapproval, if they write from the heart. But if he tries to suppress or falsify his natural emotions, then the biographer’s work becomes sodden dough or dead meat or false in note. But in any case the chances are that when his subject takes control of his imagination he will be at his mercy if the man is worth writing about. (p. 437)

Just imagine if a female biographer wrote about a female subject!!…ah, but would she be worth writing about?? It is sobering to think that this is the intellectual climate that our early women academic historians operated in. It makes their few publications even more significant.

And so, for my Australian Women Writer’s Challenge this year, I’d like to consciously read and review some histories written by women. Where possible, I’ll look for histories related to my thesis to review, but I’ll try to review them as a reader, rather than for the contribution they make to my own work. I did review a couple of histories for the Australian Women Writers Challenge last year, and I found myself consciously trying to make my review more general than I might have otherwise, and I’ll take the same approach this year. Other histories I find, that are unrelated to my own work, I’ll be reading just as anyone else would, as I won’t have much pre-existing knowledge to bring to the book.

I often feel a bit diffident about reviewing books when I know that I’m going to run into the author- which is quite likely when reviewing Australian History books by Australian historians. I get an attack of the M. H. Ellis-es, and I feel that I really have no right to review and that I should just slink out of the room. But I shall stand tall (take that M. H. Ellis!!), knowing that on the few occasions when the connection has been made “Oh, so YOU’RE the Resident Judge!” (and I cringe at the presumption of my blog-name), there has never been any unpleasantness- to the contrary, in fact.