It is hard to think away out of our heads a history which has long lain in a remote past but which once lay in the future.

F.W. Maitland ‘Memoranda de Parliamento (1893) in Selected Essays (Cambridge University Press, 1936) p. 66

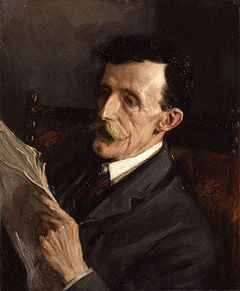

F. W. Maitland– now where have I heard that name before? I’m only too well aware of how limited my knowledge is of ‘older’ historians, but the name seemed familiar. I have been reading about Sir Peregrine Maitland in Upper Canada and I thought that perhaps I had the two mixed up. But then I realized that a picture of F. W. Maitland was on the cover of the conference program at the legal history conference I attended at Cambridge a few weeks ago- in fact, he was the Downing Professor of the Laws of England at Cambridge between 1888-1906. That surprised me: the quote above seems somehow more reflective and almost postmodern than I would have expected from a 19th century legal historian.

F.W. Maitland was a philosopher at heart, who went into the law for largely pragmatic reasons and came to history rather late in his prolific, but rather short, academic career. At the age of 25, and as part of his quest to earn a Trinity Fellowship he wrote and self-published a treatise called ‘A Historical Sketch of Liberty and Equality as Ideals of English Political Philosophy from the Time of Hobbes to the Time of Coleridge’. Much of his academic work elaborated on this foundation, whereby he unearthed, transcribed and commented on the broad sweep of English law, right back to Roman and Anglo-Saxon law. From this he developed a sweeping vision of social relations and modernity both in Britain and the Anglo-world, and on the Continent. While solidly a records-based historian, grappling with legal, highly technical documents, his works revolve around the larger philosophy of ideas exemplified by de Tocqueville, Adam Smith, Montesquieu and Marx. Although a prolific writer- over 5000 pages- much of his work was conducted in spite of ill-health through tuberculosis, and he died in 1906 at the age of fifty-six.

On the 4th January 2011 a memorial to him was placed in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey, the only professional historian to be honoured in this way. Quite apart from his interest in history and law, and his clear, evocative writing, his approach to history itself speaks to me. He was deeply conscious of the dangers of anachronism:

The history of law must be a history of ideas. It must represent, not merely what men have done and said, but what men have thought in bygone ages. The task of reconstructing ancient ideas is hazardous and can only be accomplished little by little. If we are in a hurry to get to the beginning we shall miss the path. [… ]Against many kinds of anachronism we now guard ourselves. We are careful of costume, of armour and architecture, of words and forms of speech. But it is far easier to be careful of these things than to prevent the intrusion of untimely ideas. […] ‘The most efficient

method of protecting ourselves against such errors is that of reading our history backwards as well as forwards, of making sure of our middle ages before we talk about the “archaic”, of accustoming our eyes to the twilight before we go out into the night.[…] Above all, by slow degrees the thoughts of our forefathers, their common thoughts about common things, will have become thinkable once more. F. W. Maitland, Domesday Book, p. 356, p. 520

He knew the importance of starting in the right place to find the essence of the structure.

Too often we allow ourselves to suppose that, could we get back to the beginning, we should find that all was intelligible and should then be able to watch the process whereby simple ideas were smothered under subtleties and technicalities. But it is not so. Simplicity is the outcome of technical subtlety; it is the goal, not the starting point. As we go backwards the familiar outlines become blurred; the ideas become fluid, and instead of the simple we find the indefinite. F.W. Maitland, Domesday Book p. 9

References:

Alan Macfarlane (a renowned social anthropologist in his own right) F. W. Maitland and the Making of the Modern World. It’s downloadable as a PDF here and it displayed brilliantly on my e-reader- being able to read long PDFs in a book-like form without having to print off- now this is what an e-reader does really well.

A You-Tube video Alan Macfarlane lecturing on F.W. Maitland in 2001 in the Department of Social Anthropology, Cambridge University. There’s no bells and whistles here- it’s just a straight out, softly-spoken, chalk and talk lecture that assumes familiarity with Maine, Montesquieu etc (an unfounded assumption in my case!) but it convey’s Macfarlane’s deep admiration of Maitland and the significance of Maitland’s work.