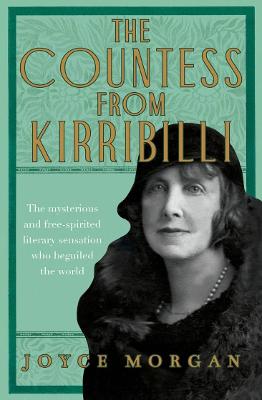

Perhaps Joyce Morgan is channelling the spirit of Mary Beauchamp/Elizabeth von Armin, the subject of this biography, in choosing such a deceptive title. Particularly for those of us who do not live in Sydney, Kirribilli is synonymous with the ‘second’ Prime Minister’s Residence located on the shores of Sydney Harbour ( a cause for some interstate disgruntlement when the incumbent Prime Minister is from NSW and spends most of his time on Sydney Harbour rather than in Canberra). So who is this Countess?

It’s all a bit misleading, because when young Mary Beauchamp lived at Beulah House in the suburb of Kirribilli, she was certainly not a countess. She was born in Australia in 1866, with an English-born, merchant father, and a Tasmanian-born mother Louey. After living in several houses in Kirribilli, they finally shifted to a (now demolished) waterfront house, Beulah, close to their wealthy maternal uncle Frederick Lassetter and his family. When she was three, her father decided to follow the Lassetters when they returned to England. Mary – or ‘Elizabeth’ as she was better known through her first book Elizabeth and her German Garden, a name which she adopted permanently as a widow, – never returned to Australia again. She made no claim to Australian identity, and it’s interesting that she has no entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

So where did the ‘Countess’ part come from? She gained the title through marriage to Count Henning August Arnim-Schlagethin, a Prussian aristocrat, fifteen years her senior who, while titled, had also inherited his father’s debts. They lived in Germany, and she soon found herself burdened by serial pregnancies with three children in less than three years, five in total. She and her husband spent much time apart. Mary and her children lived in Nassenheide, in a dilapidated schloss, which she renovated. It was a marriage marked with conflict. After Henning died, her next marriage, to Earl Frank Russell (grandson of Lord John Russell the Prime Minister) and brother of Bertrand Russell, was no happier. She kept her ‘Countess’ designation, but now she was Countess Russell. She seems to have swung between happiness and misery in a tempestuous and emotionally labile second marriage. After this marriage broke down, she had other affairs, possibly with her friend H. G. Wells, and with Alexander Frere, who later became a noted publisher, 27 years her junior and literally half her age.

Her former brother-in-law Bertrand Russell warned his children “Do not marry a novelist”. He was right. Elizabeth’s life and experiences very much informed her books, and she drew on both her husbands as characters in her books, and not to their advantage. Framed humourously at first, but then in a more sinister light, she called the Henning-like character in first book Elizabeth and her German Garden ‘the Man of Wrath’. When she wrote The Pastor’s Wife in 1914, the epynomous pastor was Prussian, and took his innocent English wife Ingeborg to provincial life where (like Henning) he studied agricultural developments, and kept her constantly pregnant until an artist (not a writer, as H. G. Wells was) came into her life and convinced her to leave. Vera, seen as the darkest of her books is a “terrifying portrait of domestic tyranny” (p. 185). The husband in this story, Wemyss, takes his young wife Lucy to a gloomy house The Willows (very similar to Frank Russell’s house Telegraph House) where he works to exact total submission from his wife through his moods, vile tempers and manipulation.

Elizabeth worked hard as a writer, almost constantly working on a book. She made sure that she had a working studio in each of the homes she created, and would keep working even when hosting an ongoing stream of visitors. To be honest, I hadn’t heard of any of her 21 books, which seem to range from whimsy to some rather dark domestic themes and back to memoir again. In a literary biography, there is a narrow line for authors to tread between giving the flavour of their subject’s writings for those who have not read them on the one hand, and delving into a more detailed analysis that assumes that the reader is familiar with them on the other. I think that Morgan handled this well, demonstrating the variety that can be found in von Armin’s writing, integrating these largely-autobiographical works into her telling of von Armin’s life, and encouraging the reader to actually read her books.

Most striking is just how well connected in a literary sense Elizabeth von Armin was. Her cousin was Katherine Mansfield, with whom she had a close, but at times, strained relationship. She counted H. G. Wells, E. M. Forster, Rebecca West, D. H. Lawrence amongst her friends and acquaintances, and she knew innumerable people amongst the English intelligentsia. She lived through both the first and second World Wars, fearing for two of her daughters still in Germany, and apprehensive about the Jewish connections in her first husband’s family. Even though she hated travelling by sea in a time when air travel was not yet available, she travelled and lived in various places in Europe and visited those of her children living in America.

She was an idiosyncratic mixture of exhibitionist and dissembler. She wrote best-sellers under a non-de-plume for almost 30 years before her identity as ‘Elizabeth’ was definitively established. She kept secrets from her friends and family and she burned many of her letters (which fortunately the recipients kept). Yet she treated her life as raw material for her semi-autobiographical writing, thus putting her family and friends into the public arena, without consulting them.

Joyce Morgan has presented an enigmatic, fascinating woman who lived a life very far removed from an Australian experience. She has a light touch as a biographer, starting each chapter or section with a narrative, scene-settling, imaginative paragraph or two, as if she is coming up for air, before diving down into description and analysis again. This leads to a fairly ‘choppy’ sort of reading experience, but it also keeps the biography at an easily-accessible level. It is only when you turn to the back of the book that you realize how well she has integrated primary sources into her narrative, drawing on journals and letters by Elizabeth, Katherine Mansfield and H. G.Wells. A rather odd coda has been added to the book where Morgan delves further into von Armin’s Australian family history, almost as if the author feels that she needs to ‘prove’ her Australian-ness which is otherwise incidental to the rest of Elizabeth von Armin’s life.

For me, Morgan has piqued my curiosity sufficiently to seek out one or two of Elizabeth von Armin’s books, and Gabrielle Carey’s biography as well. For a biographer, I’m sure that means ‘mission accomplished’.

My rating: 8.5

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library.

I have included this review on the Australian Women Writers Challenge Database.