2016, 256 p.

There is no shortage of memoirs about parents written by their children. Too often, there is an underlying whine of grievance in such memoirs – admittedly, quite often justified- because the parents are too cruel, too self-absorbed or too mad, and the author/child is seeking to blame or understand (and often both at once). Alternatively, there are memoirs of parents bathed in nostalgia, sorrow and yearning: yearning for a return to a simpler time and regret for lost opportunities and all the things the author did not say at the time.

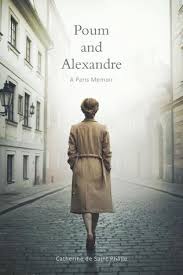

Poum and Alexandre falls into neither of these camps. It’s significant that the title makes no reference to the author at all – there’s no ‘my’ in the title- and the subtitle ‘A Paris Memoir’ emphasizes place. The book is written from the child’s point of view, but the author’s own life, and most particularly her adult life, is largely absent, except in the final section. The book is written in three parts: ‘Poum’ dealing with her mother Marie-Antoinette, nicknamed ‘Poum’ because of a childish game in bouncing down stair ‘poum, poum, poum’; ‘Alexandre’ dealing with her father; and then a final short coda involving both parents.

Both Poum and Alexandre are eccentric. Poum is a disinterested mother, just as happy to stay in bed with her books, as to spend time with her daughter. Alexandre imbues his daughter’s mind with Greek myths, praise for the Magna Carta, and tales of Napoleon. Both parents are drawn to tales of blood and savagery, and they share these with their daughter, irrespective of her age.

Their daughter, Catherine, spends much of her early life away from her parents. Born in England, ostensibly because of the freedoms bestowed by the Magna Carta, she is largely raised by her nanny Sylvia, and Sylvia’s own family. When she finally settles in France, she can barely speak French, and the book is largely devoid of friends or any other contacts other than her family.

Told from Catherine’s point of view, there are many gaps and non-sequiturs. Alexandre is already married and has an older, first family and what seems to be an ever-increasing number of offspring that Catherine gradually learns about, but does not meet. Alexandre and Poum are cousins, and have fallen out with their families over their relationship. Poum tries doggedly to maintain relations with her own family, but there is tension and resentment, and Catherine feels it. This ‘situation’ swirls around Catherine and her parents, marking them out as different and disreputable. Perhaps it’s this exclusion that turns them towards each other in a fey, irresponsible and downright strange way.

Yet there is no judgement here. Catherine describes them with love and acceptance, even though as a reader you find yourself raising a sceptical eyebrow or huffing with disapproval at the sheer irresponsibility that both parents display at different times. The book is beautifully written, and it certainly subverts the chronological memoir genre. It shuttles backwards and forwards, and tells events from multiple perspectives. It withholds as much as it gives. And yet at the end of the book, you realize just how much Catherine has given you as a reader, and you are left with a puzzling and yet rich view of her parents – much how the author finds herself. This is a challenging memoir, but I suspect that I will remember it long after the ‘misery memoirs’ have merged one into another.

Read because: CAE bookgroup selection (mine). And several people on the Australian Women Writer’s Challenge website had read it

My rating: 8

I have added this review to the Australian Women Writers Challenge database