2017, 192 P & notes

I can remember how disappointed I felt when I first read Graeme Davison’s article ‘Sydney and the Bush:an urban context for the Australian Legend’, published in Historical Studies in October 1978 [1]. It was written some 20 years after Russel Ward’s The Australian Legend and it argued that the bush legend sprang not from the trenches of the goldfields or Gallipoli, but from the streets of central Sydney. How un-bush-like! I couldn’t remember the details, but I did remember a map of Sydney, with dots depicting all the places where the ‘bush’ writers (Lawson, Price Wurung) lived, often in boarding houses and close to the radical centres of urban Sydney life. Where were the ‘lowing cattle’ and stringy eucalypts there?, I wondered.

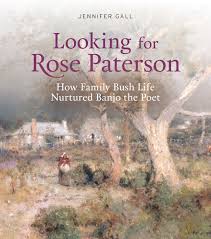

I’ve only just gone back to look at the article to refresh my memory, and my eye snagged on Davison’s qualification that “’Banjo’ Paterson was the one important figure with even fair ‘bush’ credentials” (p. 192) That’s good, then, because I’ve just finished reading Jennifer Galls’ book Looking for Rose Paterson: How Family Bush Life Nurtured Banjo the Poet. The crux of her argument is that Banjo (Andrew Barton) Paterson’s short stories and poems like Clancy of the Overflow and The Man from Snowy River drew on his childhood upbringing in small country towns in New South Wales (close to Orange and then Yass) and the influence of strong women of the bush- women much like his mother, Rose.

The author, Jennifer Gall is a curator at the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra, and this is at least the second book of hers that has been published by the National Library of Australia. I’ve been thinking about why a library, in particular, might publish a book about an individual. In some cases, the subject has achieved fame, and the documentation held by the library or museum might be published to add an extra dimension to their already-public character (I’m thinking, most pertinently, of Germaine Greer’s archive which is about to become available from the University of Melbourne archives). Alternatively, the library or museum may hold a collection that is notable for its completeness, or the illumination it throws on otherwise-undocumented, lived experience, but the creator him/herself is unknown (and I’m thinking here of the Goldfields Diary held by the State Library of Victoria). In such cases, the publication of a hard-copy, illustrated book would be a way of bringing the wealth of that particular archive to public attention.

Looking for Rose Paterson is a combination of both these spurs to publication. As the title and cover design lettering suggests, this book is indirectly a commentary on the famous Australian writer Banjo Paterson, but the larger emphasis is on his mother Rose Paterson, rather than her son. The book is based on the collection of thirty nine of Rose Paterson’s letters written to her younger sister Nora Murray-Prior between 1873 and 1888 and available online at http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/650061 The letters had once been part of the Murray-Prior estate and were crammed into an old sea-chest that had been cleared out of a family home. In this regard they are like the family letters of any family that has had the education to generate and value the letters in the first place, and the wealth and stability to keep family documents through a limited number of shifts of location and strong family ties. The letters were purchased by academic Colin Roderick, author of several books on Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson, who recognized the significance of the placenames and personalities (Banjo himself and Nora’s step-daughter the author Rosa Praed) and hence the letters also have value because of their links with famous people. Roderick published the letters in 2000 and offered the letters to the National Library.

So who was Rose Paterson, other than Banjo Paterson’s mother? In her own right, she lived and died without recognition beyond her family. She was born in 1844 in Australia, four years after her parents had arrived separately in the colony on the same ship. She was part of the lineage of a pioneering pastoral family. Her mother had educated her at home, along with her siblings in a standard classical education- English and French, and an introduction to the rudiments of Latin, Greek, German and Italian. She married at the age of 18 in one of those sisters-marrying-brothers constellations found in many family trees. Her husband, Andrew Bogle Paterson was often absent on pastoral work on the three stations co-owned by the brothers in NSW and Queensland. When the elder brother John died suddenly at the age of 40, his remaining brother Andrew lost the stations but was kept on at their Illalong station as an overseer. It was in this environment that Banjo Paterson grew up, with his three siblings and cousin, and it was here at Illalong that Rose wrote to her younger sister Nora, who lived with her much-older husband Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior along with her twelve step-children and eight own children. One marvels that Nora had time to correspond, but judging from Rose’s side of the correspondence (Nora’s is lost), she clearly did, facilitated most probably by money and material comforts that her sister Rose lacked. After the death of Rose’s husband in 1889, the connection with Illalong was severed and Rose shifted to her mother’s house at Rockend, in Gladesville, Sydney where she died in 1893 at the age of 49.

These are just the sort of letters that a historian craves. There is continuity and detail, and they provide an entrée to the world of women who have intermarried into a small subset of pastoralist families and who are known to each other. Although Rose’s life at Illalong was hard, she maintained her connections with her much more genteel and refined pre-marriage life. The line between a wealthy squatter and an impoverished one was a permeable one because of clan connections, particularly in the Scots pastoral fraternity. If you’re looking for details of interactions with the indigenous people who had either been ‘turned away’ or still lived and worked on the stations, you’re not going to find them here. Instead, through the intimacy of sisters who see each other on occasion at their mother’s house in Sydney and who take an interest in their nieces and nephews, we gain a family-based, woman’s-eyed view of childbearing, motherhood, parenting and social life. In this, I was reminded of the repository of letters by Anna Murray Powell in Upper Canada, and Katherine McKenna’s wonderful use of them in writing A Life of Propriety. However, in Gall’s book the narrative is driven by themes rather than chronology, and what rich themes they are!

In Chapter 1 ‘This poor old prison of a habitation’, the circumstances by which Rose ended up at Illalong are detailed, but the chapter then moves to a discussion of sewing, mending, trousseaus and marriage. Chapter 2 ‘All utilities and no luxuries’ highlights the drudgery of farming, the isolation and cheerlessness of living on a remote station, and the financial strain of drought and the poor remuneration for overseers. Ch. 3 ‘Smuggle a bottle of chloroform’ was absolutely fascinating in exploring the experience of pregnancy – a topic that is delicately avoided in most colonial correspondence, particularly when the correspondence itself is infrequent, addressed to and read by the men of the family, and covering months of news, rather than the day-to-day. The two sisters write about the pregnancies, births and losses of mutual acquaintances, and Rose’s letter to Nora after her nine-month-old baby died gives the lie to the assumption that parents were inured to the loss of children at a time of high infant mortality. They write of the search for doctors, or failing that, ‘gamps’ – midwives- and plans for confinement where there will be assistance. Gall points out that Australian women were more likely to call on a doctor during their confinement than women in Britain and Europe, who turned to midwives instead, suggesting that this might reflect the disproportionate rate of men to women in early decades of Australian settlement.

There is an abrupt change of pace and direction in Chapter 4, where Gall returns to the ‘Banjo’ thread of her narrative. I found this rather jarring, as the spotlight is turned to the son, rather than the mother. Having noted the dearth of commentary about Aboriginal people in Rose and Nora’s letters, it was startling to turn the page to see a full-length portrait photograph of Banjo, known to the family as ‘Barty’, aged possibly 2 or 3, sitting on a chair with his Aboriginal nurse Fanny, who was barely more than a child herself. Rose accuses ‘that horrid Black Fanny’ of allowing him to climb trees and injure his arm, but there is no other comment in the text (and presumably in the letters) of the presence of Aboriginal people on the station or in the domestic setting of the home. This chapter is more chronological, briefly tracing through Banjo Paterson’s career, the writing of Waltzing Matilda and his work as war correspondent. Was this chapter necessary? I think maybe not, or perhaps it could have been better incorporated into the introduction, because it broke the narrative thread of the other chapters.

Chapter 5 ‘Judicious neglect and occasional scrubbing’ returns to the domestic world of childcare, child rearing and education. As an educated woman herself, Rose placed high importance on education for both her sons and her daughters, and she sought to secure the best tuition she could with the limited money available to her. For her sons, this involved boarding in Sydney to attend Sydney Grammar School, but for her daughters this involved tuition through a governess, and later through boarding with school teachers in nearby Yass, and the passing on of skills from one sister to another. Chapter 6 ‘No better dower than a good education’ continues this theme, describing the career paths and life choices available to Rose’s and Nora’s daughters. Rose’s awareness of the literary success of Nora’s stepdaughter Rosa Praed, and her responses to the books that she is reading hint that Rose could, perhaps, have been a writer herself – like Louisa Lawson perhaps? Chapter 7 ‘We shall have a fine houseful’ describes Roses’s social life and larger cultural world, which encompassed what could be termed ‘bourgeois’ families in the local area, wider contacts within the intermarried squattocracy families, and at her mother’s house in Sydney. The chapter discusses etiquette, the importance of the piano, visiting protocols, weddings and country balls- and here again I was reminded of the Powell family in Upper Canada and the transference and ubiquity of middle-class domestic practices across the colonies of the Empire.

The book finishes with a short summary of Rose Paterson’s legacy and returns to the theme announced in the title of ‘How family bush life nurtured Banjo the poet’ – something that I wondered if Gall was going to return to at any stage. The book closes with an expression of regret that no photo had been found of Rose, but as we read in the obviously-later-written introduction, there is a photograph of her- and what a beautiful photograph it is.

The book is interspersed with reproductions of Rose’s letters on yellowed paper, with the ink faded to brown, and occasionally cross-written (the historian’s curse!). There are lengthy quotes from the letters in the text, marked with the icon of a pen-nib to denote when the original has been reproduced on the adjoining page, and as a reader you never felt that the author was holding the sources back from you. The book is lavishly illustrated with images, only few of which relate directly to the Paterson family. At times I wondered if the images were being used too tangentially. Barely two pages of text passed without an illustration, and the ‘coffee-table’ presentation tended to detract from the scholarship of the work, in the quest for atmosphere and context.

I very much enjoyed this book. As a historian of a ‘famous’ man myself, this archive of correspondence is just the sort that I craved and sought in vain, in trying to flesh out the domestic world that lies behind us all- famous and unknown alike. Gall has served us well, in presenting the archive, contextualising it within the milieu of nineteenth century Australian pastoralism, and drawing out the themes of women’s lives in that class and environment. I felt sorry to leave Rose- or rather, sorry that she left us- a sure sign that a letter can reach across time and generations.

[1] Graeme Davison ‘Sydney and the Bush: an urban context for the Australian Legend’ Historical Studies, vol 18, no 71, October 1978.

Source: Review copy NLA, courtesy Scott Eathorne, Quikmark Media

My rating: 8.5/10

I am posting this review to the Australian Women Writers Challenge.

I am posting this review to the Australian Women Writers Challenge.

I am posting this review to the

I am posting this review to the