1985, 106 p.

I don’t really know how to review a book of short stories. I find myself making several assumptions. I assume that it is a selection from a corpus of work developed over a period of time: it is common to find that several stories in a collection have appeared in other compilations previously. I assume that someone– author? editor?- had a vision for a book of short stories as a self-contained piece of work. I assume that one story was accepted as ‘right’ but another put aside for now, and that the ordering of the stories was a conscious and carefully thought out decision. There’s an arbitrariness about the whole process that makes it hard to think about a book of short stories as a single object: would it be any less satisfactory if one of the stories had been omitted? would it be a different entity with one of the stories that was rejected included instead? For me, even the act of reading a collection of stories differs from my normal reading habit. I prefer to read them just one at a time, but often they’re so short that I find myself thinking “Well, what now?” Sometimes I cram in another one straight away (which I don’t like doing), or else turn afterwards to another full-length book that I might have on the go at the same time. When I come to write about them here, I’m not sure how to proceed- do I treat them individually (which might become rather tedious and might place a heavier burden on a few pages of writing than it can support)? Do I just hold onto the one or two that stay with me even without opening the covers again? Or do I embrace it instead as a collection without peering too closely at the component parts?

I’ll go with the memorable stories, without looking at the book again. The first one, which gives the collection its title fitted in neatly with another book I’d read recently- Life in Seven Mistakes. It is uncanny how often one book seems to ‘speak’ to another. This short story is located in Surfers Paradise too, but the narrator is more mature and thus easier to spend time with, and Garner adeptly uses the device of postcards written over a period of time to quickly shape the contours of a larger plot that stretched over a longer expanse of time. Good, sharp, clever writing.

Her story ‘Little Helen’s Sunday Afternoon’ captures a child’s perspective well, and evoked for me those visits to my mother’s friend’s houses, where there were other barely-known children and mutual wariness and showing-off. In ‘All Those Bloody Young Catholics’ she nails the drawl, condescension and prejudices of the slightly-tipsy narrator of some thirty years ago when sexism and sectarianism were threaded unselfconsciously and largely unchallenged through overheard conversations. In ‘Did He Pay?’ she describes vividly the washed-up, unattached old rock-star, indulged by friends and committed to no-one.

I’ve always seen Helen Garner as a perceptive observer, who has gone to places that I never dared, several years ahead of me. There’s an innate authenticity in what she describes, and I can see why so much of her more recent work straddles the conjunction of non-fiction/reportage/fiction. As a Melburnian, I love the very local context of her narratives, although she ventures overseas, particularly to France, in these stories as well. It’s like looking through someone else’s eyes at the things, people and situations that surround you, and thinking “Yep, she’s got it!”

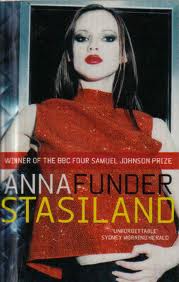

It’s interesting that this book has had so many lives. My copy is an early 1986, and there is a 1992 one as well; it was republished in 2008 as one of Penguin’s Modern Classics with the cover above, and most recently it has appeared as one of the orange-and-white retro (and cheap!) Popular Penguin reprints.

Rating: 8/10??

Reason read: Australian Literature Group (Yahoo Groups)

(4.5 /5)

(4.5 /5)