2012, 236 p & notes

I must admit that I don’t very often come away from the ANZLHS Law and History Conference rushing to my library website to look up a book. I did, however, with this book last December only to find that it already had multiple reservations. I put a hold on it in December and finally received it in May. Perhaps they should buy another copy….

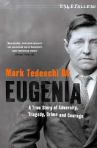

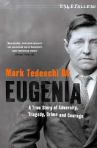

You’ve probably seen or hear of Mark Tedeschi QC, even if you don’t know you have. He’s the NSW Senior Crown Prosecutor, and he has been involved in a slew of important and famous criminal trials: Ivan Milat’s Backpacker Murder; the trial of the men who murdered the heart surgeon Victor Chang; the trial following the assassination of politician John Newman; the Gordon Wood case over the death of Caroline Byrne at The Gap; and Counsel assisting the Coroner in the 2007 trial into the killing of the Balibo Five. It was in his role as Senior Crown Prosecutor that he addressed a gathering of former and present Crown Prosecutors gathered at NSW Parliament House in 2005 to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the appointment of the first Crown Prosecutor, Frederick Garling, in 1830.At that presentation he listed a number of extraordinary, complex and bizarre trials, and first on his list was that of Eugenia Falleni. In the introduction to this book he writes:

In the intervening years, I have come to consider that the trial of Eugenia Falleni in 1920 should be viewed as the single most important criminal trial of those 175 years. Its prominence is not because of any lasting effect that the trial had on the law or the administration of criminal justice, but rather because of the multitude of legal and social issues that Eugenia’s life and trial throw up for us to consider, so that we can use them as a yardstick to ask ourselves what we have learned and how far we have progressed since then.” P. 228

So who was Eugenia Falleni? I’m wary of spoilers, so I’ll cite from the publicity on the back cover.

Eugenia Falleni was a woman, who in the 1920s was charged with the murder of her wife. She had lived in Australia for twenty two years as a man and during that time married twice. Three years after the mysterious disappearance of Annie, her first wife, Eugenia was arrested and charged with her murder. This is the story of one of the most extraordinary criminal trials in legal history anywhere in the world. The book traces Eugenia’s history: from her early years in New Zealand, to her brutal treatment aboard a merchant ship and then her life in Sydney, living as Harry Crawford- exploring how Harry managed to convince two wives that he was a man, culminating with Annie’s death, the police investigation, Harry’s second marriage to Lizzie, and then arrest for Annie’s murder three years after she had disappeared.

The book is written in three parts. The first, ‘The Search for Love’ takes us up to the trial. Many chapters start with a paragraph identifying the year and listing a number of events that occurred that year. It reminded me a bit of the technique in the film Same Time Next Year where each new encounter was separated from the last by a film clip of significant events. So, in this book Chapter 5 is set in 1913, marked by Roland Garros’s flight from France to Tunisia, Emily Pankhurst’s jail sentence and the commencement of work on Canberra. It’s rather repetitive and overt, but on the other hand I could actually name the years in which events took place instead of just having a vague idea after a single date is given at the start of the book , then not mentioned again.

The book is written using fictional techniques, but it is not fiction. There are conversations in the book, and frequent internal dialogues where the author suggests the thoughts of various characters. Despite the spoiler on the back cover, there is little foreshadowing of events that will unfurl during the story.

In his introduction, Tedeschi signals how he is going to deal with his sources. He writes:

The historical facts of Eugenia Fallini’s story that I have related in this book, including quotations from newspaper reports and evidence from her trial, are based upon contemporary public records, press reports, court transcripts and other written accounts, as well as subsequent recollections of people who had direct contact with the main personalities. I could have provided footnotes or endnotes for the historical facts, but I believe that including numbered notes in a text creates a visual and psychological hurdle for the reader to overcome. For this reason, I have instead included a bibliography at the end of the book and I have only inserted numbered endnotes in the text where they are essential for an explanation. Where I have referred to personal thoughts and emotions, these are generally inferred by me from the background factual circumstances in which they occurred. Most conversations are taken from police statements or evidence given in the committal proceedings and the trial. In those two instances (in chapters 1 and 8) where, in the absence of established facts, I have engaged in conjecture about significant events, I have clearly indicated that this is the case and stated the basis for my supposition. P. xiv.

I didn’t find this particularly satisfactory. The bibliography at the end of the book is divided into legal documents, newspaper articles, obituaries and family histories, and secondary sources. The legal documents, which are probably the most important, include the transcript of the trial, the judge’s trial notes, the register of post mortem examinations , NSW female penitentiary records and a police statement. Yet in the text itself, there is no indication which document a particular fact draws upon and thus no way of the reader weighing the authority and interests that the statement reflected. The footnotes are more like explanatory notes e.g. conversion of imperial measures into decimal, biographical details of minor characters, or references to tangential legal cases. Occasionally, though, there are footnotes directly related to the narrative.

He makes many assumptions about his characters’ state of mind without indicating the basis for his reconstruction . For example:

Over the long weekend, Harry languished in his kitchen over a bottle of whisky, agonising about what would become of Annie’s fourteen-year old son, and indeed himself, without Annie. When the boy returned from his long-weekend holiday at Collaroy with the Bone family, how was he to break the terrible news to him that his mother had gone off without telling him or even leaving a note, leaving him with his stepfather? He felt great sorrow for this boy who had lost his father when he was very young and who now faced being informed that his mother was gone. P 66

There is no indication of the evidence he used for deducing Harry’s feelings about his stepson, or whether this ‘terrible news’ of Annie’s desertion was clearly thought through rather than an excuse conjured up on the spot. We do not know whether this reflects Eugenia (Harry’s) own confession, the step-son’s testimony, or Tedeschi’s assumptions- and surely that matters.

In his introduction, he particularly signposted Chapter 8 as a section where he was creating his own explanation. I cannot fault the care with which he does so in the opening paragraphs of that chapter:

There were only two people who knew exactly what happened next in the clearing at the Lane Cover River Park: Harry Crawford and his wife, Annie. Neither of them was in a position afterwards to give an account, for reasons that will become apparent. What follows is therefore a possible version of events, re-created by the author, that is entirely consistent with all the known facts that later emerged, but interpreted with the benefit of today’s superior knowledge in the forensic sciences and unimpeded by the considerable prejudice that existed at the time for someone in Harry Crawford’s predicament (p.55)

What follows is a narrative that is highly sympathetic to Harry Crawford (Eugenia). It is very much the sort of legal narrative that a defence counsel could create, but it is oddly placed in Part I, which is a straight chronological account. The author gives no indication of the evidence from which he has drawn up the scenario, and once created, it skews the rest of the narrative. What would I have done, were I writing this book? I think I might have created this narrative, and then immediately created a counter-narrative. Perhaps I would have put it in Part II where Tedeschi writes as a lawyer, or perhaps at the end of the book. I would certainly, at least identified the sources for my explanation here, if not elsewhere. This chapter has no notes at all.

It is in Part II of the book (“Legal Proceedings”) that Tedeschi really hits his straps. Using his legal knowledge, he examines the investigation and trial from beginning to end, noting discrepancies and anomalies and distinguishing changes in the law from the early 20th century to today. He notes flaws in the Crown’s case and is particularly scathing of Harry’s defence lawyer. You’re very much aware of the lawyer at work here. He creates a long list of fifteen alternative questions that the defence layer could have but did not ask, and embroiders the narrative with the rhetorical flourishes that a lawyer in full flight might use: for example, a succession of paragraphs that each end with the sentence “it has not always been so” or in another section listing things that the defence lawyer could have done “but would he do so?” Whatever my misgivings about the first part of the book, only a barrister could write this second section.

Part III, “Incarceration and Release” examines Eugenia’s life after she has been released from prison. Here he quotes more directly from medical reports, oral histories and newspaper articles, and I felt as if I was on surer evidentiary ground. It is only a short section and rather sad. He concludes with a retrospective that reviews the trial from a 21st century perspective. It’s an interesting chapter. Finally, there is an appendix that follows up on the main characters and what happened to them later, and the places and institutions in which events occurred. I’m not really sure that it was necessary as an appendix because the story stood well on its own two feet.

The book addresses the issue of sex and gender directly. It’s a fairly human response, I suppose, for us to wonder “But surely his wives would have known that she wasn’t a man?!” and Tedeschi goes into quite a bit of detail about the object coyly referred to in the court cases as “the article”.

I found myself returning again and again to the police photograph of Harry on the front cover. It was taken immediately after his arrest. Not only had he been charged with the murder of his first wife, but his second wife now knew about his false identity. He was afraid that he would be placed in a male prison with his identity as man/woman common knowledge. There’s cockiness and yet sorrow in his face, and he had every reason to be fearful.

It’s a compelling story and, quite apart from the narrative itself, this book has raised so many methodological questions for me that I want to read more. How would a journalist deal with the story, or an historian? Tedeschi acknowledges his debt to Suzanne Falkiner’s book, and I know that the historian Ruth Ford has written about her as well. I haven’t finished with this story yet.