2016 Update: I have rather cheekily linked to this post as part of the National Family History Month Blogging Challenge which, during Week 1, asked for a post about things people had learned about their ancestors through the Census. Well, as you’ll see, this posting isn’t really about a family at all, but rather it looks at the controversy over one of the questions in the 1841 census. So, here’s my posting from 2011:

15 August 2011.

My census paper is all filled in, waiting to be collected. I quite enjoy filling in surveys and doing interviews. I note that several of my Facebook friends with young babies were amused at the inappropriateness of many of the questions to their babies (“How well does the person speak English?” “Does the person ever need someone to help with self care activities?”). At the other end of the parenting spectrum, I found myself feeling rather furtively curious at the replies given by adult children (Hmmm- so that’s how much they earn?! How did they answer the unpaid domestic work for the household question?)

My son was rather keen that I answer ‘No religion’ in the optional religious question. It’s obviously a touchy subject because it, alone among the questions, is optional. Thinking back to the rigid, unyielding sectarian prejudices of my 1950s-60s childhood, this would have always been a hot question but for different reasons. What’s a Good Unitarian Girl to do? Yes- I know that identifying as Unitarian will be collapsed into a bald statistic showing the increasing religiosity/atheism of modern society. Do I want my creedless religion collapsed into a category along with fundamentalists of all shades? How religious is a creed-less religion? Such deep questions, all for a census.

Then there’s the marriage question. It’s when there’s such a stark choice- married/divorced/widowed/never married – that I feel uncomfortable about the many shades of grey that are blurred by such harsh distinctions. The long term same-sex relationship that would dearly love to be a marriage but is forbidden?

And the either/or nature of language spoken at home.

Radio National’s Rear Vision program had an excellent feature recently called Who Counts? A History of the Census (podcast and transcript available). The program highlighted that censuses (censi?) differ in their questions, format and intent in different countries at different times. The British census of the mid-19th century, for instance, reflected the public health concerns over ‘the household’ as an economic unit, particularly in the wake of the widespread mobility of the Industrial Revolution. The American census was framed by a mindset of growth, particularly on the frontier.

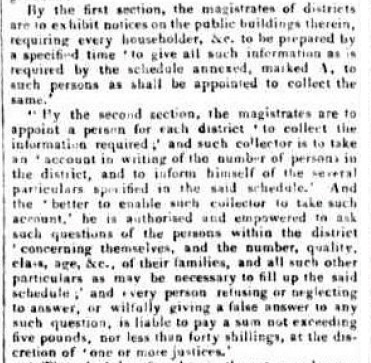

The Australian census, first conducted in 1828, emerged out of an earlier tradition of the convict muster. As shown on the Historical Census and Colonial Data Archive site, there were censuses in New South Wales in 1833, 1836 and 1841. The Census Act of 1840 spelled out the process for collecting the information, and the magistrates were at the heart of it:

[Australasian Chronicle 5 December 1840]

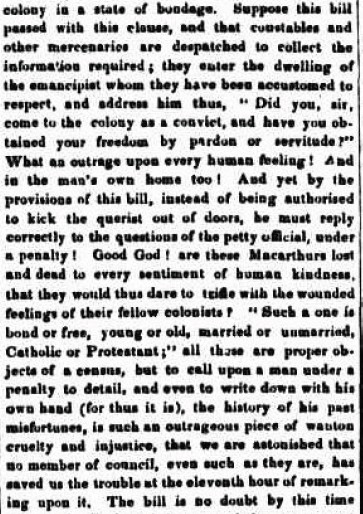

During the 1840 debate over the Census Bill, the process was not controversial, but one of the questions in particular was:

whether he was born in the colony, arrived free, or obtained freedom by pardon or servitude?

The original census of 1828 provided several “class” categories: CF meant ‘came free’; BC meant ‘born in colony’; CP denoted ‘conditional pardon’; FS meant’ free by servitude’ and TL stood for ‘ticket of leave’. But by 1840 New South Wales was distancing itself ever further from its convict origins – a process which John Hirst in Convict Society and its Enemies argues began right from the start of settlement. This question was now highly sensitive. As the Australian Chronicle argued:

[Australian Chronicle 20 October 1840]

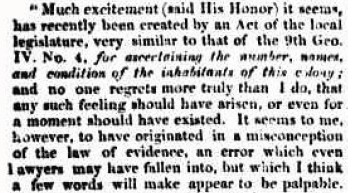

And into the fray steps- yes, you guessed it!- Judge Willis. Justices Dowling and Stephen, the two other judges of the Supreme Court of NSW declared the bill to be repugnant to British Justice on the grounds that, as a witness under oath in court did not have to degrade his character by identifying himself as an ex-convict, he should not be required to do so before a census collector. Justice Willis, as was his right, issued a dissenting opinion, arguing that the benefit of the question for the government outweighed this consideration (although he did not specify what these benefits were to be). As was often the case with Willis’ interventions into political questions, at issue was not his dissent per se but the way in which he expressed it (although in this case, it highlighted tensions between the ‘exclusives’ and the ’emancipists’). In court he observed:

With this subtle, but nonetheless public put-down of his fellow judges, he then went on to discuss the laws of evidence in the courts and concluded:

This public jousting on a question of law was one of several issues between Willis and his brother judges, most especially Chief Justice Dowling, at the time. Along with other similar considerations, it led to Gipps’ decision to place Willis as the resident judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in the district of Port Phillip, well away from his colleagues.

So, I can hand over my completed census form- minus any questions about my convict status or lack thereof- safe in the knowledge that yet again, I have operated on the principle of six degrees of separation between Judge Willis and any topic you may choose to name, and managed to bring Judge Willis into 2011, no matter how tenuous the link.