As part of examining Judge Willis’ interaction with Port Phillip society, I’ve read folder after folder of official correspondence, column after column of newspapers, memoirs and several diaries. But one thing that I have barely dipped into is personal correspondence. So it was armed with a few names that I headed into the State Library yesterday- off to read the correspondence of the Burchett brothers who arrived from 1839 onwards to their family ‘back home’, and a thesis based on the correspondence of Alexander F. Mollison who visited Melbourne in its earliest days, then settled in the Port Phillip district from about 1837.

The survival of any cache of correspondence is a mixture of luck, diligence, intent and circumstance. There are those rare individuals who keep copies of all correspondence both sent and received, but it’s more likely that an archive of correspondence is likely to be largely one-sided, usually consisting of letters received, with the letters sent reflected only obliquely. The preservation of letters within a family depends largely on the importance placed on them by the recipient, and the custodians to whom they pass when the recipient dies. Then there is another step between private ownership and their availability to a wider public through a museum (where they can linger undiscovered and uncatalogued for years) or publication.

Moreover, the practice of mail correspondence between New South Wales and the metropole, particularly during the 1840s, reflected the realities of a 4-6 month time lag with a swag of letters arriving in one dispatch, or likewise, no mail appearing at all. No doubt the receipt of letters would trigger off a frenzy of response, with the minutae of day-to-day life telescoped into a potted narrative that would reassure loved ones who were totally unfamiliar with the sights, smells and local personalities on the other side of the world. On both sides, the pictured recipients would be kept in a mental time-warp that kept them as they were when last seen, with shared acquaintances and memories given more prominence than perhaps they merited. I tend to think of this correspondence as similar to the word-processed Christmas updates we all started to include in our Christmas cards a few years ago, up until they fell out of favour for being homogenized, impersonalized and too cheery and cheesy. (Mind you, I enjoy receiving them and still do send them- cheesy and impersonalized though they may be).

So, with these constraints in mind, how likely is it that any of this correspondence would mention Judge Willis? I guess that it depends on how personally involved the writer was with the agitation to either remove or support him, which in turn might reflect the political engagement and interests of the intended recipient of the letter. How much of any politics would filter through, say, into the Christmas Update we might send today? I suspect that 2001 Christmas Updates reflected the shock of September 11; we may have written to overseas correspondents about a change in government. But, unless personally involved, it’s not likely that day-to-day politics is likely to find its way into correspondence intended for an overseas readership, even in our connected, globalized world, and probably even less so from 1843 New South Wales.

The Burchett Brothers

And so to the Burchett letters. The copy of the letters I saw had been typewritten and photographed. Now, there’s nothing quite like the pleasure of the looped, cursive script, the browning ink and the texture of the paper of the original. But I’ve been there, and done that, and there’s also nothing quite like the regularity and ease of a typewritten transcript!! They were catalogued under “Burchett family”, and the collection includes letters written by Charles Gowland Burchett (1817-1856), Henry Burchett (1820-1872), Frederick Burchett (1824-1861) and Alfred Burchett (1831-1888). The boys arrived out here over a period of time, with the 22 year old Charles and 19 year old Henry arriving first in 1839, followed by their younger brother Frederick, aged 16, the following year. I’m not sure when Alfred arrived. There were obviously other children still left at home- Henry’s letters in particular are full of high-spirited and affection in-jokes with his younger siblings. All the same, it must have been hard to have your three eldest boys heading off across the globe at such young ages.

Charles, in particular, seems to have been of a slightly more political bent than his brothers. In his letter to his father on 12 June 1841 he writes about a meeting to petition the Home Government for separation from New SouthWales, and mentions the Resident Judge obliquely in reference to Sydney’s neglect of Port Phillip- a comment by then obsolete given that Judge Willis had by that time arrived in Melbourne.

Even in Sydney they know little of us. Fancy the wilful blindness of a tardy determination to allow us the services of a Supreme Judge three times in two years.

This was to be his only mention of Judge Willis. He goes on:

The principal evidence of the moral advance of this place may be enumerated as follows- a Society lately formed on the plan of the “Highland Agricultural Society” for the promotion of Agriculture, Horticulture and Breeding, William Mackenzie Esq, the son of a Scottish Baronet is the Chairman. Two or three hundred chapels; the church, however, on account of its ambitious pretensions, is at a standstill for want of funds, a considerable part of the edifice completed evidently exhibits the intention of the Trustees to make it a handsome structure- it is of stone. And last, but not least, the Mechanics Institution. Among the lectures at this last has been one “On the Influence of the Press in disseminating knowledge” by George Arden, the Editor of the Port Phillip Gazette. This said G. A. (the Boy Editor, as he is called) I have known since my arrival here; he gave a splendid speech at the meeting.

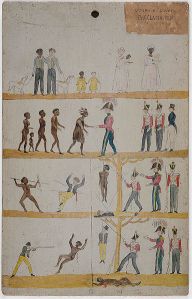

The boys established a run called ‘The Gums’ near Mt Rouse in the Western District. In a letter dated 1 Oct 1841, Frederick was not pleased by the news that Charles Sievewright was to establish the Western District Aboriginal Protectorate nearby:

There is a rumour that a Black protector is coming to take up his station at Mt Rouse, with his tail of 4 or 500 blacks, if he does we shall have to keep a sharp lookout, as the gentleman of his suits have been playing up a hurricane (colonial phrase) down below, and they are not very remarkable for their honesty

Five days later his brother Henry added:

How little do the good people at home, who are instigators of benevolent systems of civilization understand the character of these barbarous cannibals.

The financial depression of the early 1840s hit the Burchett boys badly, and Frederick returned home, followed by Charles who arrived back in England on the Glenbervie on November 24 1843. They obviously did not stay: Frederick returned to Van Diemens Land in March 1844 and the others must have returned at some stage too. Charles died in 1856 at their property St Germain’s (near Echuca); Henry died in 1872 at “Albert Road, Regent Park” (not sure where); Frederick died in 1861 in Melbourne, and Alfred in 1888 at St Kilda.

Alexander Mollison

And so on to the second batch of letters from Alexander Mollison, this time as part of a thesis written by Marie Hyde who transcribed and annotated the letters as part of a Bachelor of Letters degree in 1988. Alexander Fullerton Mollison (1805-55) has a higher profile that the Burchett brothers with a shared entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography with his brother William Thomas.

Alexander arrived in Sydney in 1834 at the older age of 29, and did not ever marry. After an exploratory trip to Port Phillip in 1836, he overlanded down from his property at Uriani (near present day Canberra) with his flock of 5000 sheep, 634 cattle, 28 bullocks and 22 horses, to establish Colliban Station, near Malmsbury. He was joined by his brothers Patrick, who was based in Sydney, another brother Crawford, and William aged 22, who arrived in 1838 who joined Alexander at Colliban. A fifth brother, James, aspired to be an artist and several of Alexander’s letters warn him specifically not to come to the colonies, as there were few prospects for artists here. Two sisters were left at home: Jane, to whom many of the letters are addressed and for whom Alexander obviously had a great affection, and Elizabeth. Again, I find myself thinking about the parents left back in England with their daughters, with the ‘boys’ of the family so far away.

The early letters reflect Alexander’s interest in the zoological and botanical sciences- and I assume that sister Jane shared this interest too. Although he didn’t send her actual specimens- as Judge Willis was wont to do with patrons he wanted particularly to impress- he did write long descriptions of rainbows he noticed at sea and his first sighting of a platypus. Zoe Laidlaw, in her book Colonial Connections 1815-45: Patronage, the Information Revolution and Colonial Government, highlights the importance of scientific networks, and the overlap between amateur colonial naturalists and visiting scientific professionals. It also evokes for me the burgeoning interest in science more generally reflected in another book I’m reading at the moment- Richard Holmes’ The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science. It seems that Alexander was very much a man of his times.

As Hyde points out, the shipboard voyage

had positive benefits as an interlude between the old world and the new in helping to establish that network of connections with the well off and influential that would serve him well in years to come.(p. 5)

He travelled with the Rusden family, little realizing that the 12 year old son George would later become Clerk of the Executive Council and a member of the National Board of Education. He became friends with Charles Nicholson, who was later become Sir Charles Nicholson, statesman, landowner and businessman.

In an odd conjunction, he wrote to his father that Henry Burchett (of the letters above) had arrived at the station to learn sheep farming before striking out on his own. The Burchett letters also resonate when the Aboriginal Protector Parker took up land on the Loddon to establish a Protectorate. Unlike the Burchetts, Mollison willingly gave up land for the Aboriginal station, and assisted Parker in running it.

Alexander obviously spent some time in Melbourne where he mixed with the other ‘respectable’ pastoralists. On 26 December 1839, he wrote to his sister Jane about the Melbourne Club:

I do not remember having told you about the Club House in Melbourne. The Inns were found to be so dirty and disordered that several respectable settlers and townsmen formed a club about 18 months ago. William and I are members. There are now eighty permanent members. The house affords twelve bedrooms, a dining room, drawing room, library and smoking room or [?]. The bedrooms are rather small but exceedingly comfortable and well-kept. Each member is allowed to occupy a bedroom one week and then must make way for another if required…The yearly subscription is five pounds and the charges are the same as at the inns.

His respectability gave him access to the political sphere. Soon after La Trobe’s arrival in Melbourne, Alexander and his brother Crawford called on him. To his father, Alexander wrote:

Mr La Trobe arrived at Melbourne some weeks ago. He told me that he had been introduced to you. I called once at his offices with Crawford but came away as soon as our business was finished, as Mr La Trobe seemed to be very much occupied. He is so far in public favor here and seems to be candid, sincere and unostentatious.

He also met with Governor Gipps when he visited Melbourne, and was one of the five men deputized to make a welcoming address to him. In October 1841 Alexander wrote to his father:

We have had great doings this past week in honour of Governor Sir George Gipps’ first visit to this district, but I have not time to relate them. I may however say that I was one of a deputation to draw up and present an address and also the president of a public dinner of one hundred and fifty people. Sir George is frank, clever, and a ready and pleasing speaker. I was introduced to him during my late short visit to Sydney.

When his friend Charles Nicholson put himself up for election as the Port Phillip member for the first District Council, Mollison seconded his nomination. Nicholson was elected the representative for Port Phillip on the part-elected Legislative Council in 1843, served as Speaker in 1846 and twice more before the granting of responsible government. Mollison was one of the inaugural members of the Melbourne branch of the Australian Immigration Society in 1840 (Garryowen p. 492); he addressed a meeting against the resumption of transportation (Garryowen p. 524); he presided over a Squatters Meeting in June 1844 and a committee member of the Separation Association (Garryowen p 907). He was made a Justice of the Peace.

It’s not surprising, then, that Mollison does mention Judge Willis’ suspension, albeit briefly, with the terse comment that “he certainly deserved it”. Mollison does not seem to have been particularly heavily involved in the movement against him, however, declining to sign the anti-Willis petitions. Both Alexander and his brother William did , however, sign a letter in support of Lonsdale who was under attack by Judge Willis, and another letter on 14th June 1843 directly before Judge Willis’ amoval complaining about aspersions raised in the court in relation to the magistracy generally.

The sheer distance between the colonies and the family at home was reinforced for me by the report of Patrick’s illness in Sydney. Charles Nicholson notified Alexander that Patrick was gravely ill, and within days Alexander was writing a second letter to say that he had died. In his will, Patrick left his colonial assets to his sister Jane and Alexander, although they did not cover his debts. Jane had obviously advanced money to Patrick, and Alexander later made an investment of Jane’s money in land on the portion bounded by Highett, Lennox and Erin Streets, Richmond. Davidoff and Hall’s book Family Fortunes notes that the daughters of a family often made their inheritance available to their brothers for investment, in return for a roof over their head and keep.

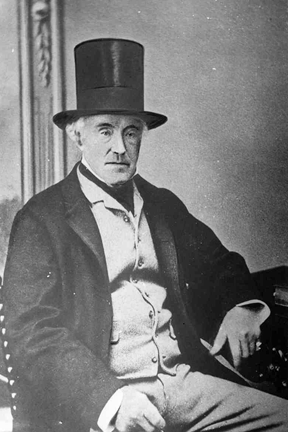

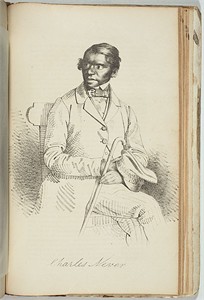

Although he suffered financially during the Depression, he did not go under, which is a testimony to his good management and frugality. By 1845 he was writing “I now begin to feel that my home is here.” He did return to London in 1850, where he stayed for 8 1/2 years. A photograph held by the State Library of Victoria taken in London during this time, describes him as

Seated, wearing three-piece suit with fringed black and white paisley patterned tie (probably a scarf). He has a full brown and gingerish beard speckled with grey, and wears a light coloured top hat with a very high crown.

He returned briefly to Victoria, then went again to England where he lived for another 13 years. After the death of his beloved sister Jane, he and his remaining sister Elizabeth returned to Victoria in 1873. They settled together, unmarried brother and sister, until he died after years of ill-health in 1885.

References:

Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850

Edmund Finn (Garryowen) The Chronicles of Early Melbourne

Richard Holmes The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science

Marie Hyde Letters from Port Phillip: the letters of Alexander Mollison 1833-1859 (thesis)

Zoe Laidlaw Colonial Connections 1815-1845: Patronage, the Information Revolution and Colonial Government

A. G. L. Shaw A History of the Port Phillip District