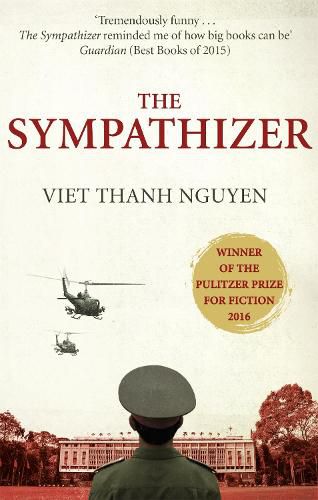

“Have you read The Sympathizer?” asked my son as we were planning our trip to Vietnam. Great book, he said although I did have a qualm or two as I packed it. Would it would be viewed as suitable reading matter should the Customs Officers at Ho Chi Minh city airport decide that my cases needed to be inspected? It is a great book, and no one had much interest in my suitcases at the airport after they had been scanned. It was the winner of the Pulitizer Prize for Fiction in 2016, and a worthy one too.

Framed as a confession written by an unnamed Vietnamese double agent for the shadowy Commandant, the narrator is a Vietnamese army captain who is working under cover for the North Vietnamese. We do not know who the Commandant is, or in whose custody our narrator is, or why. He is obviously being told to rewrite his confession because there is something missing, so it is a slippery narrative.

Our narrator is a man of divided loyalties on many sides: his father was a French priest who took advantage of his young, now deceased mother, and he is shunned as not being ‘properly’ Vietnamese. His closest friends were Man and Bon, and they shared the scar on their hands that they made as blood brothers. They did not, however, share their politics, as Bon becomes an ardent South Vietnamese patriot in exile in America with our narrator. During the war, our narrator worked with the American troops, and after the war he infiltrates the South Vietnamese diaspora community based in America. He becomes a sort of cultural consultant for a film which sounds very much like ‘Apocalypse Now’ (and indeed, books about Coppolla and the making of the the movie are credited in his references) and at times the book is quite funny as the Auteur reveals his complete disregard for the Vietnamese people who are just fodder to his film-making vision.

But the confessor’s hands are not clean. When suspicion arises that there is a mole in the diapora community, he fingers a man he calls ‘the crapulent major’ instead, and assassinates him. When a journalist called Sonny moves in on a woman he has fallen in love with, he assassinates him too. According to this clearly self-serving and written-to-order confession, he is haunted by these two deaths, although early crimes committed in his presence are left unnamed.

The ending of the book is graphic, but I found myself wanting to push through to find out who the commandant, and his superior the commissar were and how he found himself in this situation- a sign that the narrative strength of the book could overcome my own squeamishness.

My enjoyment of the book was probably enhanced, having read it in Vietnam, immersed in museums commemorating the struggle for independence and the end of the war, and moving through areas that were just names in the news reports of the 1960s and 1970s. But even had I read it in cold old Melbourne, I still would have been fascinated by the split nature and slipperiness of the narrative, and the situation that led our confessor to write this tract.

My rating: 9/10

Read because: I was in Vietnam