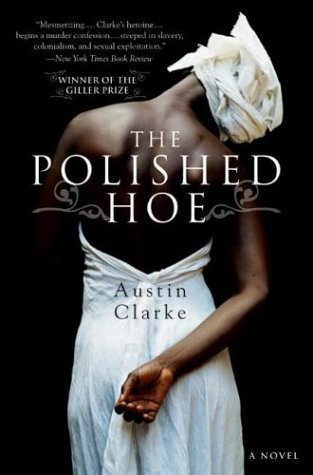

Well, Scheherazade may have been able to spin out her story over One Thousand and One Nights, but Mary-Mathilda, the mistress of plantation owner Mr Bellfeels, and the mother of his only sons, takes only one very long night to tell her story. But it’s a very long night, and the story takes over 513 pages. Alone in the Great House on the plantation, she has called the police station on a Sunday night to confess to a crime. The Constable is dispatched to house to “pacify Miss Bellfeels” until the Sergeant, whom she has known since childhood, can arrive to take her statement. This is the story of that night, and the conversation that flows back and forth between Miss Bellfeels and first the Constable and then the Sergeant, before they take her statement about a crime that she has committed.

The story is set post-WW2 in Barbados, called Bimshire by the locals. The world, and Britain in particular, was happy enough to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in 2007 but the reality is that even after the expanded Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, plantations continued in British colonies, with former slaves designed ‘apprentices’ until 1838, and then subjected to a form of indentured labour after that.

Mary Gertrude Matilda was born ‘free’ on the plantation, presumably in the early 20th century. Her mother, who also lived on the plantation was probably born ‘free’ too, but the power relations of the plantation still held sway. Mr Bellfeels, the plantation owner, had taken Mary’s mother as one of his -what do you call it? Not a lover, not a mistress, nor a concubine- perhaps sex-slave (?) and Mary is only a very young girl when Mr Bellfeels corners mother and daughter in a church-yard. Still mounted on his horse, runs his whip up and down Mary’s body, claiming ownership when she is a bit older. By the time she is an adolescent, he has raped her, just as he did her mother, and he continues to abuse her, albeit more as mistress than slave, setting her up in a house on the plantation where she bears his only son. With the malicious irony of the oppressor, the boy is baptized Wilberforce (who had campaigned for the abolition of slavery) and Mary Matilda occupies an ambiguous place in Bimshire society: shunned by white planter society, and treated with a mixture of deference and scorn by black society.

Mary has a hoe, that she used in the fields as a field-worker before she was sequestered away in the Great House. She has kept this hoe carefully sharpened, and it doesn’t take much imagination to know what she has used it for. The Sergeant, who has secretly been infatuated with Mary Matilda since they were children together knows too, and he is reluctant, but obligated, to take her statement. And so the story weaves around, backward and forwards, over Bellfeels’ abuse of both Mary and her mother over decades, the control of workers on the plantation, the birth of Wilberforce which places her in a different category to the other field-workers, leading eventually to Mary Matilda’s crime. It is a very slow telling.

Much of the book is dialogue, in a Barbadian patois, with Mary Matilda’s meandering narrative, interspersed with conversation with first the Constable, then the Sergeant. The book is told in three very long parts, with nary a chapter heading anywhere. This felt rather oppressive, especially reading as part of a compendium of Clarke’s writing on an e-reader, with no way of knowing how much longer the chapter or the book was going to continue for. For me, it made it feel even longer.

This book won the Commonwealth Writers Prize, the Giller Prize and Ontario’s Trillium Book Award. It is a striking book but too long and too slow for most readers -including myself- I would say.

My rating: 7/10

Sourced from: hard copy from my own bookshelves, supplemented by an e-reader version while I was on holidays.