It’s funny how particular crimes permeate your consciousness of growing up in a particular place and time. I suspect that every child growing up during the 1960s was touched in some way by the disappearance of the Beaumont children, and I know that the disappearance of Eloise Worledge in the 1970s made me frightened to sleep beside the window when it was open on an airless hot summer night, as windows always were before the days of airconditioning. (Apparently later research found that the small hole in the flywire screen in her room had nothing to do with her abduction. All that worry for nothing.)

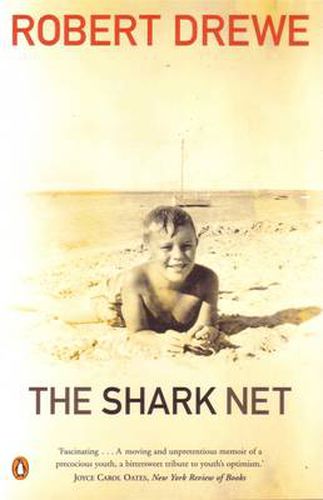

For Robert Drewe, growing up in Perth during the early 1960s, the crime that shaped his consciousness was the multiple murders committed by Eric Edgar Cooke, who was eventually hanged at Fremantle jail in October 1964. His family had shifted to Perth from Melbourne when Robert was six, on account of his father’s promotion at Dunlop Rubber, one of those 1960s brands embedded in Australian consciousness through tyres, tennis balls and Dunlopillo pillows and mattresses. His father was a Dunlop Man, who had married ‘a girl in the office’, and just like expatriates, the staff who had transferred from ‘over east’ formed a male-dominated Dunlop Family who met socially in the smaller white-collar social world of Perth.

Written from a child’s-eye point of view, both his parents were opaque to him. His father, Royce, ever the company man is depicted as a strict, slightly menacing, emotionally distant philanderer who leaned more towards his daughter than his sons. His mother, who he names ‘Dorothy’ when she was in ‘company wife’ mode, or ‘Dot’ when she was relaxed and truly herself, is a more complex character. She was never completely happy in Perth and maintained her family links with Melbourne independently of her husband and children. As Robert grows older, and his life trajectory branches out in ways that his mother disapproves of, we see the judgmental and rigid ‘Dorothy’ at work. The family splinters, under varying degrees of guilt and self-centredness.

Running alongside this memoir of family life is the story of Eric Edgar Cooke, a serial murderer who lurked around the well-to-do streets in which the Drewe family lived. A small man, often overlooked because of his cleft lip and palate, he lived on the edges of society, rebuffed by girls, married with seven children, an itinerant labourer. His life brushed up against Robert Drewe’s life in multiple ways, perhaps coincidentally or perhaps as a characteristic of life in a relatively small city. Cooke worked for Dunlop, he visited the Drewe household as part of his work, one of his victims was known to Robert Drewe, and one of Cooke’s murder implements belonged to a friend of Robert’s. There are faces at the window that may, or may not, have been Eric Cooke; he walked the streets of Dalkieth and Peppermint Grove. Later, the journalist Drewe attends the committal and murder trials that end in Cooke’s execution.

The memoir is interrupted by three independent chapters ‘Saturday Night Boy I, II and III’ which give us a glimpse of Eric Cooke. These are beautifully written, and while not exactly sympathetic and silent on his motivation, do try to explain Cooke’s life from the outside. The famed ‘light’ of Western Australian sunshine is juxtaposed against the darkness in which Cooke operated. There is a sense of menace that bubbles underneath. On driving home from being fingerprinted, as many Perth men were in the dogged search for the ‘Night Caller’, Robert’s father begins to sing the Bing Crosby song:

Where the blue of the night

Meets the gold of the sky

Someone waits for me.

Preface

He falls silent when both father and son realize the menace implicit in the words.

So, too, the image of the shark net which gives the book its title. Drewe was always frightened by sharks, and wished that the Perth beaches had been netted as some eastern beaches were:

I favoured the idea of shark nets…It wasn’t just that the nets trapped sharks, but they prevented them setting up a habitat. Intruders were kept out. A shark never got to feel at home and establish territory. I liked the certainty of nets. If our beaches were netted I knew I’d be a more confident person, happier and calmer. Then again, I might lose the shark-attack scoop of my life

p.299-300

This tension between looking for death and peril, and the desire to avoid it, runs throughout the book. He does, indeed, miss a journalistic scoop involving a friend, but it is because he is looking for sharks and not at what is directly around him. The idea that danger is amongst us, and not netted off, permeates the book.

This is a beautifully crafted memoir, with its juxtaposition of memoir and true crime, which avoids both sentimentality and prurience. It reminded me, in a way, of George Johnson’s My Brother Jack. It has the feel of being the first in a series of memoir, but as far as I know Drewe has never continued with a second book. Instead, it is a slice of life from the late 50s/early 60s rendered faithfully and lovingly but always with a sense that the sunshine and heat is coexisting with darkness and danger. Excellent.

My rating: 9/10

Read because: CAE bookgroup. I had read it back in 2002 and was impressed with it then, too.