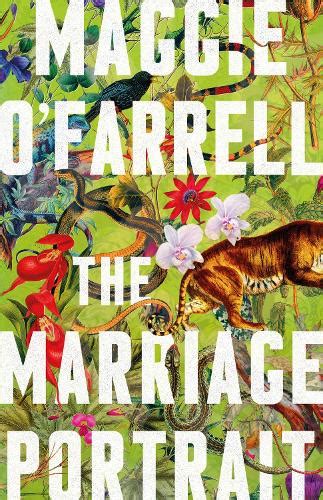

You know within a few pages of this book that there is a murder about to occur, who the perpetrator is and who the victim will be. It starts with a historical note that fifteen year old Lucrezia di Cosimo de’Medici left Florence in 1560 to begin her married life with her husband Alfonso II d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara. Less than a year later, she would be dead, with her official cause of death noted as ‘putrid fever’, but with rumours that she had been murdered by her husband. This is followed by two lines from Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’, subtitled ‘Ferrara’ where a widowed Duke is discussing the shortcomings of his deceased first wife with the emissary of his intended second wife. There is a chilling suggestion that he killed her.

Maggie O’Farrell’s book opens in Fortezza, near Bondeno, in a bleak isolated castle, and Lucrezia is convinced that her husband is about to kill her. The narrative in the story veers back and forth between this tense cat-and-mouse game, and earlier flashbacks to Lucrezia’s early life in the Florentine palazzo owned by her father, the wealthy Cosimo de Medici. We travel with her to Delizia, a rural villa, in Voghiera where she spends her early married days in a form of honeymoon; and the Castello Ferrara, the Duke’s ancestral castle where he lives with his family and where she comes to realize the mercurial nature of her husband and the dynastic imperative that she fall pregnant. We return to the forbidding fortezza near Bondeno ten times during the novel, which ensures that the tension is held throughout the novel. The book is written in the present tense, which I tend to find oppressive and straining, but O’Farrell’s choice to use it here adds to the suspense that is sustained throughout.

I liked that O’Farrell imbued Alfonso with such ambiguity that, like Lucrezia, you relaxed into his charm, only to find it whipped away in an instance. Lucrezia, astute and intelligent, only gradually realized the menace that she faced. However, I could have done without the multiple dream sequences in the book, which I always see as a rather clumsy backdoor way of advancing the story.

One of the things that I look for in a historical novel is that the characters act in a manner consistent with the norms of the time. It is not sufficient to pick up a 21st century character and sensibility, like a chess piece, and plonk it onto a historic situation that has its own expectations and coherence. Or, as historian Greg Dening put it, it is a mistake to think that “the past is us in funny clothes”. The actions need to remain consistent with the time, but the thoughts behind them don’t necessarily have to comply. As Hilary Mantel showed us, an author can stay faithful to the facts, while imbuing her characters with textured and nuanced motivations and reflections within those facts. I did think of Hilary Mantel while reading this book (which is, alas, just a shadow of her work), both in terms of the present tense voice, and also in its intent and richness of detail. But Hilary Mantel would never have written the ending of this book, and she certainly wouldn’t have foreshadowed it as clumsily as O’Farrell did. I guessed what the ending would be long before the end, and I felt rather disgruntled that she had set it up so obviously.

Nonetheless, I did find the final section of the book a page-turner, and stayed up much later than I intended to read it. It generated a good discussion, and exposed diametrically opposed attitudes towards the book at the Ivanhoe Reading Circle meeting.

My rating: 8/10

Sourced from: purchased e-book, read for the Ivanhoe Reading Circle.