This review includes references to physical and sexual violence against children.

I remember a conversation between two women my age, both lifelong Catholics, whose children had all attended Catholic schools and whose extended family rhythm moved along the course of baptisms, first communions, confirmations and weddings. Their sense of outrage by these revelations of predatory priests, shifted from church to church by the hierarchy and the secrecy and obstruction which had hidden it for decades, was almost palpable. There was a gender element to it as well: that ‘good women of the parish’ had been betrayed by powerful men into handing their children over to a dangerous situation, where the authority of the priest was so paramount that no questions could be asked for a long time.

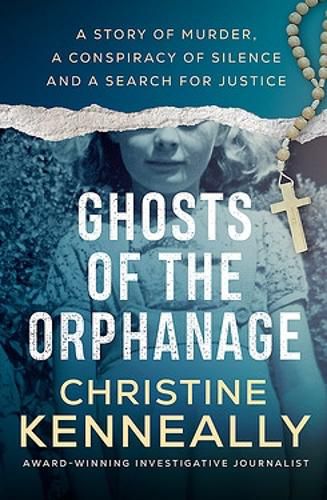

One step further again, though, is the accusation that nuns, too, perpetrated acts of physical and sexual violence against the children in their care. Not the angry, strap-happy sister of the local Catholic school -and let’s face it, many State school children have memories of shrieking teachers, the ruler and the cuts too- but the constellation of nuns and chaplains who surrounded children in church-run orphanages, where there was no escape to home, family or outside influences. Yet this is what Christine Kenneally encountered, skeptically at first, when writing first about Geoff Meyer, who lived at Royleston at Rozelle Bay in Sydney (you can read her 2012 essay The Forgotten Ones from The Monthly online) which led her on a ten-year search that took her to Vermont U.S., Canada and Scotland. Looking back, she realized that she had brushed against the system herself when she as a Catholic schoolgirl, attended a theatre camp run by Father Michael Glennon, later convicted of sexually abusing 15 children in court cases that spanned 25 years, who regularly visited a boys’ orphanage called St Augustine’s, Geelong. She was not a victim: but many other traumatized adults that she found as part of her search across Western orphanages were.

This book is the story of this search, with particular attention paid to St Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont, an institution run by the French-Canadian Sisters of Providence that operated from 1854 to 1974 which the author, Australian-born Christine Kenneally (no, not the Canadian-born Australian ex-parliamentarian) exposed in a Buzzfeed article in 2018 We Saw Nuns Kill Children. Her report drew heavily on the account of Sally Dale, who lived at St Joseph’s between the age of 2 and 23, with a short period where she lived happily with a family until she was returned to the orphanage. She claimed that she had seen a boy die after being pushed out of an upper-story window by a nun; that she had been forced to kiss a boy in a coffin who had been electrocuted by an electric fence when trying to escape; that a little girl who was tormented by the nuns to make her cry later disappeared; and that she had seen a boy drown after being rowed out onto the lake by nuns. So many deaths- surely there’s something wrong with this woman? I found myself thinking, and although finding her a compelling witness Christine Kenneally did at time too. That was until she stitched together details from other St Joseph’s children, along with death certificates and snippets of information from depositions and courtcases that seemed to go nowhere. There is so much violence reported here by multiple children: a boy deliberately locked outside on a freezing night, a girl with her hand held over fire, an ‘electric chair’ type of contraction, locked cupboards, an attic…. it just goes on and on, and I must confess to becoming confused about who told what.

Although the book focusses on St Joseph’s, she found what she describes as “an invisible archipelago” across the Western world, marked by large, dark manor houses, most 2-4 stories in height, looming large and solitary.

…they belonged to an enormous, silent network. In fact, between St Augustine’s in Victoria, Australia and St Joseph’s in Vermont, United States, existed thousands of other institutions like them: Smyllum Park orphanage in Lanarkshire, Scotland; the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Ireland; the Mount Providence Orphanage in Montreal, Canada.

p. 13

She found that the same abusive practices recurred in a litany of pain: bed-wetters having their cold sheets draped over their heads while they were paraded among jeering classmates; beatings; imprisonment in small dark places, and being forced to eat their own vomit.

I finally began to see not just one or two or ten of these places, but an entire fantastic world, a massive network, thousands of institutions, millions of children connected to one another if not by an explicit system of transport or communication, then by the overwhelming sameness of their experiences: the same schedules, the same cruelty, the same crimes committed in the same fashion, then covered up by the same organizations.

p. 15

This is a difficult book to read, and Kenneally is honest about the doubts that she, along with some of the lawyers who prosecuted cases against the church, held at times. The number of cases is numbing and overwhelming, and I began losing track a bit until I found the excellent index at the back of the book. The book raises questions of the nature of traumatic memory, and highlights the use of such questions by the defence lawyers contracted by the Catholic Church to refute the claims. By about 3/4 of the way through the book, the whole situation seemed impossible: there were too many inconsistencies, too many dead-ends, too many failed prosecutions. But in best narrative fashion, Kenneally writes about a turning point when, after years of accumulating public records, journals, legal transcripts and interviews, she gained access to a cache of documents which in turn led to the forging of a series of links that convinced her, me, and the wider public, of truths that had been there all along. I was left feeling angry and betrayed- just like the two women with whom I started this review- that the church, “one of the – if not the-most formidable entities in the world” (p. 314) has used its money and authority to garner the obedience and loyalty of its followers to protect itself alone.

All this time, survivors have been pursuing justice, but the goal of the Catholic Church is unrelated to the causes and ideals of individuals. The goal of the church is suprahuman and is measured in centuries: it has been working to control history.

p. 315

Perhaps, finally, that control is slipping.

My rating: 9/10

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library