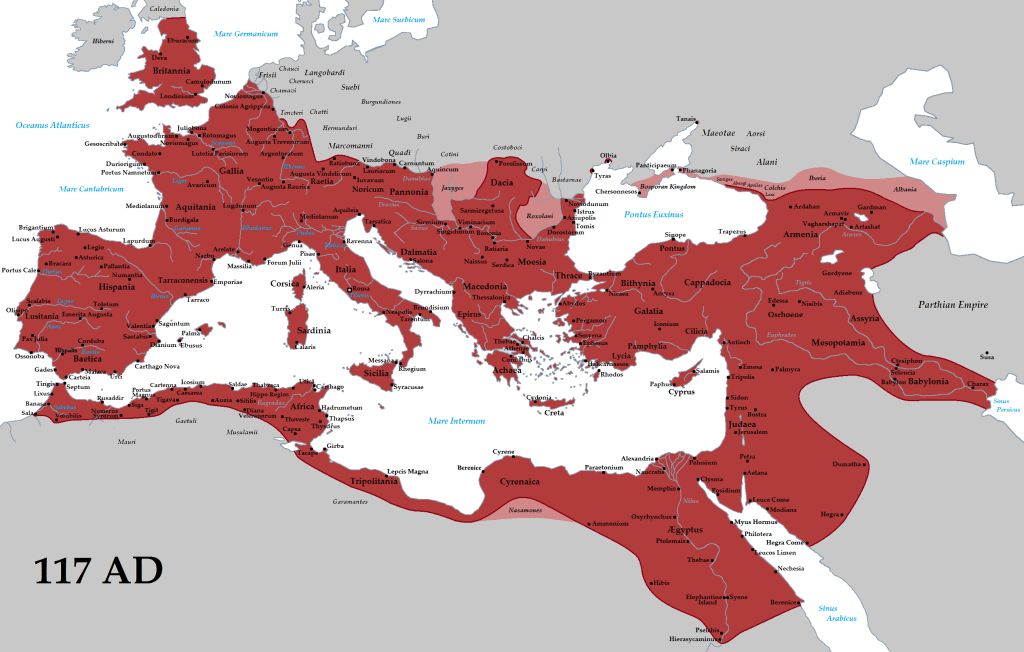

History of Rome Podcast Episode 81 The Greekling introduces us to Trajan’s younger cousin, Hadrian. He had been adopted by and brought up in Trajan’s house after his father died when Hadrian was 10. Even though Trajan didn’t push him forward as a successor, Trajan’s wife Pompeia Plotina was very ambitious for him and may have even manipulated the news of Trajan’s death to present his accession as a fait accompli. He was Governor of Syria when Trajan died, and he immediately ordered the withdrawal of troops from the recently acquired territory in the east- a very unpopular decision. But this ‘highly aggressive defence’ of the empire by withdrawing from contested and unruly territories marked his rein, and really annoyed the Senate who took pride in ‘Big Empire’. Episode 82 Hadrian’s Walls – The Romans had a god called Terminus, the god who protected boundary markers, and Hadrian today is best known for his boundaries- especially Hadrian’s wall (which was originally white-washed with a very different appearance to today) and also in North Africa, although in both cases the walls were as much for population control as anything else.. Hadrian’s reign started off with him putting down the Second Judean War, where the rather anti-semitic sources depict the Jews as being the main aggressors. After putting it down and securing Judea, he decided to reign in the Eastern boundaries and even made a settlement with the Parthians- a very unpopular policy given that the Empire had reached its widest extent under Trajan. He got off to a bad start with the senate with a string of assassinations of four ex-consuls who were accused of conspiracy against him, and the senators feared a second Domitian. However, he worked hard to appease the senate, and instituted popular acts like debt forgiveness and lots of games to win over the populace. Unlike Trajan, he micromanaged the provinces, spending a lot of his reign travelling around checking on his governors. Episode 83 May His Bones Be Crushed deals with Hadrian’s homosexuality. In many ways Hadrian was not a “roman” Roman. He loved Greek culture, he was Spanish, and he had a beard. Two things that were immediately dispensed with on his death were: 1 the amalgamation of the 17 provinces into just 4, making Rome just another province 2. The Pan-Hellenic League, a project to support the Greek city states coming together to make a powerful state. He fell in love with Antinous, a young boy (14?), who became his constant companion. But Antinous drowned in Egypt, and the grieving Hadrian deified him (which really annoyed the Senate) and started a cult of Antinous which almost rivalled the cult of Jesus. In 132 there was the second Jewish-Roman war led by Simon bar Kokhba, who claimed the independence of Judea. Hadrian crushed the revolt, in an act of cultural genocide, burning the Torah, banning circumcision and renaming it Syria Palaestina. Every time his name was mentioned, Jewish people would add “May his bones be crushed”. Episode 84 Longing for Death sees off Hadrian, dying of congestive heart failure. He had been obsessed with security and peace during his reign, and now he had to choose a successor. He overlooked his great-nephew Fuscus, fearing that he would be another Nero. He really wanted Marcus Aurelius, but he was too young. So he chose sickly, nondescript Lucius instead who died before Hadrian did. Then he chose the fairly unambitious Antoninus Pius, on condition that he adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. He did indeed long for death, and died aged 62, after ruling for 21 years.

Democracy Sausage with Mark Kenny. Lies, damned lies, and election campaigns addresses the question of civility, cynicism and truthfulness in politics. With a very good panel of Judith Brett (emeritus professor La Trobe University), Bernard Keene (Crikey) and regular podleague Dr Marija Taflaga, they come to the conclusion that things went downhill with Tony Abbott, both as opposition leader and then Prime Minister. An interesting episode.

Stuff the British Stole (ABC) It’s a living thing this time, but it was stolen anyway. Best.Named.Dog.Ever. is about the Pekingese owned by Queen Victoria, who was given a dog stolen as part of the sacking of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing in retaliation for the imprisonment and torture of diplomats in the wake of the Second Opium War in 1860. Check out the Old Summer Palace – it’s incredible, and is now more a tourist destination for Chinese people than western tourists because it has been incorporated into the Chinese ‘Century of Humiliation’ story. And what did Queen Victoria call her dog? You’ll have to listen yourself.

Boyer Lectures (ABC) Lecture 2: Soul of the Age- Order vs Chaos looks at Shakespeare’s ideas about power. Bell reminds us that Shakespeare was writing during tumultuous political times, with Mary Queen of Scots challenging Queen Elizabeth, and the Guy Fawkes terrorist plot. Shakespeare has ideas about Kingship (with Henry V his go-to guy), populism and order that he often had to drape in the clothes of past or distant civilizations. A better lecture than the first one- more specific, with better supported examples.

History This Week (History Channel) Here in Australia we always think that we are so important, and it’s always rather amusing to see how little we matter to the rest of the world. Freedom Rides Down Under looks at the Freedom Rides, based on the American example, that took off from the University of Sydney in late 1964/5 to visit outback towns in NSW. Anne Curthoys and Peter Read are featured, and there is sound footage from the time, capturing the anger in Walgett and Moree (rather oddly pronounced by the American host) when the embedded racism of the towns was publicized.