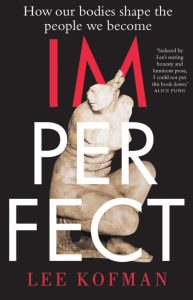

2019, 306 p

In reading this book, I alternated between anger and a vague sense of voyeurism. When I review books, I tend to avoid tackling the author and try to engage more with the words on the page, the research, the planning decisions in mounting an argument. However, sometimes the author insinuates herself so much into the text, and makes herself so much part of the whole endeavour, that it’s impossible to separate the two. The other book that angered me in this way was Caroline Jones’ Through a Glass Darkly (my review here) and the two books are similar. Both books profess to be – and are – very honest but I find myself wondering just why these authors decided to put themselves on the page like this at such a personal level. They have made their book about themselves, quite deliberately. They force the reader to engage with the writer as a person. And in both cases, I think to myself “You know, I don’t think I like you much” and I want to move away. This is different from not ‘liking’ a character in a fiction book: instead, it is the whole premise and world view through which the book is filtered – and this world view is something that, as authors, these writers have decided to foreground.

Lee Kofman has undergone several bouts of surgery during her life. As a young child in the Soviet Union, she was operated on for heart problems, then a bus accident resulted in injuries to her leg that required skin grafts, leaving her with a large scar and misshapen leg. Her self-consciousness about her scars was heightened when she shifted with her family to Israel, where a high premium is placed on body image, before moving to Australia. She adopted clothes that hid what she saw as her ‘disfigurements’, always tentative about the act of revealing her body to friends and lovers. Not only is this a point of vulnerability, it is complicated further by a sense of inauthenticity and evasion – that she has pretended to be something perfect and whole when she is not.

This self-consciousness about her body and its disfigurement has bubbled through her professional life as well. Her PhD was written about concepts of the human body; she has undergone therapy with what she perceives as mediocre success; she has included in her fiction characters who are physically marred in some way. And now this book: an exploration of ‘body surface’ (her phrase) and the way that it shapes the people we become. It all starts with her.

I confess that my brittleness about her use of her own life-story as a rationale and lens springs from my own experience (ah! I’m aware of my own hypocrisy here). But in her exploration of obesity, horrific burns, facial deformities etc., and her assumption of a sense of shared experience, she personally has the luxury of the dilemma of when and if to reveal. That is a luxury denied to most of the people she interviews, whose difference is right there from the start, visible to all- not just to lovers and friends – but the curious, cruel and supercilious alike.

She admits at times that her own curiosity verges on voyeurism about other people’s experience. Her analysis is not just of imperfect bodies, but bodies that have been deliberately manipulated through extreme surgery and piercing, tattooing and shaping. She ranges far, interweaving her interviews with ‘imperfect’ people with academic research encountered as part of her PhD study. In many ways, even though I know that many readers enjoy it, I am uncomfortable with this mixture of the confessional and the academic.

She writes that her own sons have albinism. I do wonder how they will read this book when they are older. Will they see “Mummy’s scars”, which have figured so heavily in her writing and academic life, as a common bond between them, or will they resist? Will they resent being drawn into her analysis? I suspect that they may well.

Kofman gives us plenty of herself, but the voices of the people she interviews are reflected through her lens. I find myself thinking of the excellent ABC program “You Can’t Ask That” that gives time to look, and then listen. The interviewer there is silent because the questions are written on cards, and drawn from a range of questioners. Kofman is not silent.

I will probably let this post sit for a while as I ponder whether to post it. When I dislike a book, I generally don’t write a blog post about it at all. After all, I figure, if the book is a dud, then my piling-on is not going to make the book any better, or the author a better writer.

But neither this book, nor Caroline Jones’ book are duds. And in both cases, the author herself has made choices. She has chosen to place herself in the centre of her book, not just in terms of the action (as an autobiographer or memoirist might do), but to use herself as the starting point of the analysis, not just in an intellectual sense but asking you to join her in the exploration as well. In this case, I’m not comfortable with her fixation on what she sees as her own failings. Even more, I’m not comfortable with her assumption that it gives her a sense of fellow-feeling with people whose ‘body-surface’ is much more confronting and demanding than hers.

My rating: 7/10 (actually, I found this hard to judge)

Sourced from: Yarra Plenty Regional Library

I have included this review on the Australian Women Writers Challenge database.

I have included this review on the Australian Women Writers Challenge database.

Great review! I would distrust a factual book written in this way because the sample size- 1 – is too small. But in literary fiction (as distinct from story telling cum entertainment) I expect there to be only the thinnest film between the protagonist and the author. I’m glad you decided to post, it’s an interesting subject to think about.

A strong and insightful analysis of an uncomfortable study.

Thank you for capturing what I felt so well. The voyeurism and othering in this book, as well as Lee’s ability to conceal her scars when she chooses, made me incredibly uncomfortable.

Putting yourself into the narrative as a character is an established trope in literary journalism, which is the genre that this book belongs to. It has a long pedigree that stretches back at least to the 18th century and James Boswell’s ‘Life of Johnson’. In the post-WWII era many innovative writers such as Tom Wolf and Hunter Thompson used this method of conveying reality in their narratives. There is absolutely nothing unusual about this type of writing at all.

I’m well aware of the author placing him/herself within the narrative, both historically and increasingly in non-fiction genres in current writing. While the omniscient and unseen author of course filters and shapes the material, making oneself part of the story invites the reader to react to the author on a personal level, something that I’m not usually particularly comfortable in doing.

Pingback: ‘Constellations: Reflections from Life’ by Sinéad Gleeson | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

No, not for me either … thanks for your review which confirms my instincts about books like this one.

Pingback: 2019 Australian Women Writers Challenge Completed | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip