On a beautiful 24-degree summer afternoon, where more perversely pleasant to visit than a cemetery? So off we went to Boroondara Cemetery in High Street Kew, primarily to see the Springthorpe Memorial which I’d seen many times in photographs but never actually visited.

Boroondara Cemetery was established in 1858 as a garden cemetery and, with imagination, you can just sense the Victorian conceptions of death and mourning that underpinned its design. The original plan, since abandoned, was for curved paths and winding roads, but it nevertheless maintains its rather forbidding red brick perimeter wall, caretaker’s lodge with slate roof and a clocktower, and rotunda. Its most famous monument is the Springthorpe Memorial, completed in 1907 after ten years’ construction and described in 1933 in The Age as “one of the most beautiful and most costly in the commonwealth”.

It was erected by Dr. John Springthorpe to commemorate his wife Annie, who died in childbirth with her fourth child, Guy, who survived to become a well known Melbourne psychiatrist, following in his father’s footsteps. Dr. John Springthorpe had arrived in Australia as an infant and had a successful career with positions at the Beechworth Lunatic Asylum, the Alfred and the Melbourne Hospitals. He enlisted during World War I with the Australian Army Medical Corps, and on his return to Australia after the war, worked on post-war repatriation and psychiatric care (hence his commemoration in the name of ‘Springthorpe’ housing estate on the site of the old Mont Park/Bundoora Repatriation hospital). The breadth of his professional involvements is wide: training and registration of dentists, nurses, masseurs, ambulance work, maternal and child welfare. He was very much the clubbable man, and a supporter and collector of the nascent Australian artist scene of the turn of the twentieth century. It’s ironic, then, that a man who had such a rich life should be best known for a memorial that he created to commemorate death.

As a thirty-one year old, he had married the 20-year- old Annie Inglis on Australia Day 1887 and they moved into a house at 83 Collins Street east- the fashionable, doctors’ end of town. She was a first cousin to the a Beckett family, and hence the Boyd family who are so interwoven into Melbourne cultural life. Ten years later she died, giving birth to her fourth child. Disconsolate with grief, Dr Springthorpe sent his children away to live with relatives, and poured his sorrow into his diaries, transforming his house into a shrine to Annie with photographs and paintings to commemorate their married life, and leaving the house just as it was- even to the blood stain where his wife hemorrhaged to death. In the days immediately following her death, he turned to the artistic circle of Melbourne and commissioned the sculptor Bertram Mackennel to design

a piece of sculpture, all in white marble, a sarcophagus, richly traced, with certain inscriptions on the sides; on the top, a sculptured figure, as much like Annie as she lay in the drawing room as possible

And here it is

The memorial took nearly ten years to complete. The roof, made of red glass that bathes the marble in a rosy glow, was designed by Harold Desbrowe Annear.

The memorial was originally surrounded by gardens designed by William Guilfoyle, the designer of the Botanic Gardens. Later work on the garden saw the installation of two works by Charles Web Gilbert- my husband’s grandfather (and to be honest, our main reason for seeking out the Springthorpe Memorial in the first place). One of these was of a brolga defending her chicks against a snake rearing up to strike, and the other of a monk. Neither of these sculptures have survived, and it is unsure whether they were ever positioned where they were intended. However, this picture from 1929 seems to show some sort of bird with outstretched wings, and interestingly, the marble figures seem to be enclosed in a glass case. The gardens were subsumed into the rest of the cemetery when, after Springthorpe’s death, it was found that the transactions for the land had not been completed.

[Later insertion: please see the comments below regarding the further design of the gardens surrounding the memorial by Luffman/Loughman]

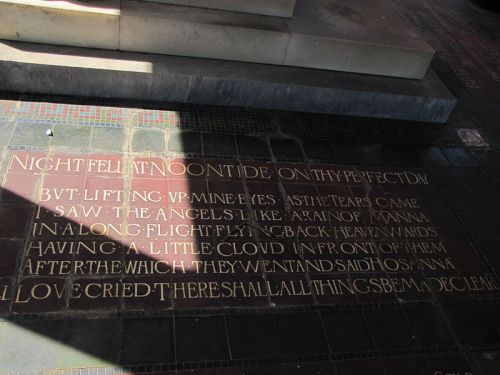

The whole memorial is heavily freighted with symbolic references, including quotations and adaptations from the Bible, the Greek classics, Walt Whitman, Wordsworth, Dante, Browning, Riley, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. There’s something just a little bit creepy about the idealization of his wife- especially given that she is not named anywhere on the memorial:

- My own true love

- Pattern daughter perfect mother and ideal wife

- Born on the 26th day of January 1867

- Married on the 26th day of January 1887

- Buried on the 26th day of January 1897

- It is a memorial deeply engraved by text:

- I found myself thinking of the pre-Raphaelites and their heavy emphasis on beauty and death. To our eyes today, there’s something rather unhealthy about it all. Maybe people even then were discomfited by such fervent obsession as well: apparently Mackennell himself warned Springthorpe that the etching of deeply symbolic and overwrought text on every possible surface might be over the top. The Bulletin concurred:

-

Turning for a last look, the tremendous monument loads the emotions, insistent, almost blatant, one thinks dully of the dead woman, ten feet below, on whose brow it must press so heavily. Only its artistic beauty, only Mackennal’s consummate genius, could have saved it from descending to the level of a gorgeous advertisement.

- The monument cost a huge amount, although it is uncertain what the final cost amounted to with figures ranging from £4,500 to £8,000-£10,000 bandied about: in today’s currency, somewhere between $700,000 and $1.3M.

- There’s a fascinating article by Pat Jalland exploring the Springthorpe Memorial as a masculine expression of grief. She wrote Australian Ways of Death. A Social and Cultural History 1840-1918 and you can access her article from The Age here. And Anne Sanders from the National Portrait Gallery delivered a wonderful presentation on Springthorpe himself and the video and transcript are well worth a look.

I think my offspring has relations at Booroondara. I just went to check the FamHist file I have … and discovered that I didn’t reinstall the program when I upgraded the computer. I wonder if I’ve lost everything….

Yes, much work has been published on Springthorpe a leading practitioner in the psychiatry field in the 1880s and who was prepared to appear in court to advocate for mentally ill people who committed crimes – something of a new thing in those days. Springthorpe followed his colleagues in UK and Australia, by recognising the vaue the freudian method of the talking cure for soldiers traumatised by trench warfare during the Great War. The Australian historian Joy Damousi wrote about it in ‘Freud in the Antipodes’. Earlier in the 90s historian Stephen Garton also wrote about him, using the Springthorpe diaries as a source. They are marvellous tomes… providing insight into the a way of dealing with death that is long gone. Was it just that Springthorpe had the money to express his grief as fully as he did, or was it that married life and family was an important counter to his work amongst very (mentally) ill people? Thankyou for this post.

Thanks for this Christine. Yes, you’re right that there is quite a bit of work that draws on Springthorpe, both in terms of his psychiatric and medical contributions, and in explorations of grief. I saw that he testified at the Frederick Deeming trial.

Reblogged this on Freud in Oceania and commented:

I am reblogging this post by Janine, a fellow historian, about the Springthorpe Memorial which is found in a Melbourne Suburb – Heidelberg. Springthorpe as I noted in my comments was a leading medical practitioner in the mental health field from the 1880s and amongst the ‘psychoanalytic pioneers’ identified by historian Joy Damousi in her book, Freud in the Antipodes. As Janine says the memorial tells us much about the Victorian way of death and mourning – so sentimental to our eyes and ears but perhaps this is a product of a fantasy of invincibility, where death is so often sooshed away.

Springthorpe was a very well connected man, wasn’t he? To the a Beckett family, the Boyd family, he worked with Bertram Mackennel and with William Guilfoyle and presumably other cultural icons of his day. Very clubbable indeed!

C Web Gilbert Brolga and Monk

Just over a decade after the death of his beloved Annie, Dr Springthorpe decided to extend the memorial with re-landscaping of the grounds, including the creation of a rectangular pool, two seats, a sundial and commissioning two sculptures. He sought the advice of horticulturist, Charles Loughman, and engaged the young sculptor, Web Gilbert, to produce two works. One – and this is this one – a bronze casting of a brolga mother bird with her two chicks and a snake poised to strike. You can see the analogy with his wife about to be killed with her children. The other, a carved marble relief of a monk, based upon the Tibetan master in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.

(Was this later part of the The Wheel of Life, topped with bronze pagoda roof and 2 dragons heads – knocked off as souvenirs?)

Although both works were completed in 1909, there is dispute as to whether they were ever positioned next to the reflective pool in the memorial.

Janine’s blog January 3, 2013.

The memorial was originally surrounded by gardens designed by William Guilfoyle, the designer of the Botanic Gardens. Later work on the garden saw the installation of two works by Charles Web Gilbert- my husband’s grandfather (and to be honest, our main reason for seeking out the Springthorpe Memorial in the first place). One of these was of a brolga defending her chicks against a snake rearing up to strike, and the other of a monk. Neither of these sculptures have survived, and it is unsure whether they were ever positioned where they were intended. However, this picture from 1929 seems to show some sort of bird with outstretched wings, and interestingly, the marble figures seem to be enclosed in a glass case. The gardens were subsumed into the rest of the cemetery when, after Springthorpe’s death, it was found that the transactions for the land had not been completed.

Hello Morna! I hadn’t thought about the monk statue at all. Somehow it being a Tibetan monk and mentioned in Kipling’s Kim fits in with the highly ornate and idiosyncratic symbolism that surrounds the whole gravesite. I wonder what it looked like?

Hi Janine, from what I can tell the monk was a carved marble relief on a block of marble, not a 3D statue, based upon the Tibetan master in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. A website I recently googled seems to tie the story together: http://www.stephenwhiteside.com.au/the-wheel-of-life

Whiteside is a CJ Dennis fan and appears to have taken a recent interest in his co-Sunnysider C Web Gilbert so he has a number of posts on the sculptures. Steve’s cousin Wendy was here in Qld last week so I’ve been chasing up a lot of interesting facts on our Grandpa.Gilbert (and Grandma the Artists Model).

Morna and Janine

I quote from the transcript of my lecture on Dr John Springthorpe, given in May 2011, at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra:

“Just over a decade after the death of his beloved Annie, Springthorpe decided to extend the memorial with re-landscaping of the grounds, including the creation of a rectangular pool, two seats, a sundial and commissioning two sculptures. He sought the advice of horticulturist, Charles Loughman, and engaged the young sculptor, Web Gilbert, to produce two works. One – and this is this one – a bronze casting of a brolga mother bird with her two chicks and a snake poised to strike. You can see the analogy with his wife about to be killed with her children. The other, a carved marble relief of a monk, based upon the Tibetan master in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.

Although both works were completed in 1909, there is dispute as to whether they were ever positioned next to the reflective pool in the memorial. And I suspect events overtook this intention.

Charles Loughman, the horticulturist, was well-known to the Tuckett family, particularly Margaret Tuckett, who had in 1905 written a very popular and informative book on her splendid Victorian garden, called simply, A Year in My Garden. In 1909 the Tucketts had decided to sell the property, Omama, in rural Murrumbeena.

It’s quite possible that Springy had known Mr Tuckett, whose office was in Collins Street. Springthorpe would also have been aware of the Omama Gardens through the books, also through his friendship with Loughman and possibly through Tuckett. He was also a regular visitor in the area as he passed through Murrumbeena on his way to see his children in South Gippsland. And also, from 1907, his regular visits the Talbot Epileptic Colony, which he helped establish.

In 1909, the Omama Garden was sub-divided and Springthorpe purchased the house and garden and two adjoining blocks, totalling four and a half acres. The two sculptures were relocated to the wild, contemplative section of the garden, just beyond the Torii Gates to the Japanese Garden. You can see the two Torii Gates here. And this is those two works in-situ in the wild part of the garden [I am referring to the slides].”

Black and white photographs of the sculptures were reproduced in an article on the garden for the magazine Table Talk. These were used in the accompanying slides for my talk and are visible in the video, which you link to. Further, Web Gilbert’s Web of Life sculpture was sold as part of the estate sale through auction house Leonard Joels just after Springthorpe’s death in 1933. The work was purchased and a later date gifted to the University of Melbourne and is now in its collection. See this link for an interview with Ray Marginson and the fate of some of the University’s sculpture collection: http://www.unimelb.edu.au/culturalcollections/research/collections9/03_Robyn-Sloggett.pdf.

Thanks for your interest. By the way, the lecture was part of series of public programs designed to accompany the exhibition, Inner Worlds: Portraits and Psychology, which toured to university galleries including the Ian Potter Gallery at the University of Melbourne. The exhibition, which included new scholarship, drew on Prof Joy Damousi’s work in Freud in the Antipodes and I also was in contact with Prof Pat Jalland regarding Springthorpe as well as drawing on the excellent art historical references of Deborah Edwards and Dr Harriet Edquist with regard to the creative collaboration that was the memorial.

Dr Anne Sanders

Art historian and curatorial researcher, National Portrait Gallery Canberra.

Hello residentjudge

I found it again – the dragon head article – so it all ties together!

Click to access 03_Robyn-Sloggett.pdf

I haven’t been to this cemetery but intend to in the near future. My gr grandparents are buried there.

Gr grandfather Alexander Falconbridge and his wife Catherine (Quin) from County Donegal in 1880 arrived with their 6 children on the Marpesia.

Just 12 years later Catherine died suddenly in their home in River Road Richmond from a kidney disease (possibly from the many child births she had undergone)…The following month Alexander aged 62 fell into a vat of boiling starch in the Lewis & Whitty starch factory in Richmond and was pronounced dead upon arrival at the old Melbourne Hospital. They left 9 living orphaned children aged from 24 down to just 12 months. My grandmother Catherine was 17 years old at the time.

Valerie Price-Currer

Hi

i think i might have a quinn connection for you , my ancestors were catherine quinn ( father Patrick John, mother Nancy Bridget ,Ballintra, Donegal Co Donegal, Ireland

Donal Quinn

Hi Donal I have just come across this message so please forgive me for not responding before this. Your information sounds very hopeful. Grandmother Catherine Quin Falconridge’s father was said to be John Quinn, farmer of Donegal. Mother unknown? Is there anything else you can tell me? No Nancy has been found in the family, nor Bridget.

I believe a Patty Quinn has done a lot of work on the Ballintra Quinn family but nothing conclusive has come of it re my family.

Would like to hear from you, thank you. Valerie

Valerie

Trying to contact you regarding your Boyd-Falconbridge family from Prestonpans to Dowles Shropshire and beyond in the 1700s. I believe my 4 x great grandmother and 4 x great grand uncle may have migrated from Prestonpans to Dowles & Bewdley along with your Jean Boyd & Samuel Falconbridge, so interested in making contact. Hope to hear from you. Katie in Holland.

Just to add, Valerie, that I’m working on the theory that myt 4th great grandmother and her brother as mentioned were siblings of your Jean Boyd.

Hi,

And a thanyou to Dr Sanders.

But the mystery still continues – what happened to the brolgas that were a part of the Springthorpe memorial? Web Gilbert’s symbolic “tribute to Motherhood sacrificed on the altar of duty”, as quoted in “THE HIPPODROME magazine, London, 1917 (British Artists and their Work Series)”.

I seem to recall, rather vaguely, that Dr Juliet Peers (now at RMIT in Melbourne) did look for this work many years ago, with no success. Rumour was that it might have ended up in someone’s garden, maybe on Mount Macedon. But it has not surfaced.

Another curious point is that the Talbot Leprosy Colony in Clayton that Springthorpe had established in 1907 has the same name as the town where Web Gilbert was brought up. A coincidence? It was a small artistic world in the early 1900s!

Steve Gilbert

Hi Steve, I am a 3rd year History student at La Trobe Uni researching Web and Mabel Gilbert (and their children) and Garry and Frank Roberts. I would love to chat with you if you are so inclined. I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely, Donna Baldwin

Hello Donna. I’ve referred this on to Steve.

Thank you Janine … much appreciated.

Pingback: The Melbourne Expedition – Days among the dead: the Springthorpe Memorial. | The mind is an unexplored country.

I was brought up in Kew and used to walk through the cemetery on my way from school to the weekly woodwork classes at Glenferrie. This was in the middle 1950s, and the marble sarcophagus with its attendant angel were certainly within a glass case at this time.

From memory, my mother, who had been a senior nurse, had known Guy Springthorpe and told me the story of the memorial.

I should imagine that such a striking memorial would be very memorable. Thanks for giving a date to the glass case

Gilbert’s Wheel of Life survives, and it was in the foyer of the University of Melbourne’s School of Medicine building on Grattan St about ten years ago:

https://stephenwhiteside.com.au/category/web-gilbert/

The name of the horticulturist was Charles Luffman, NOT Loughman. He was the director of the Burnley School of Horticulture for some ten years. Volkhard

Thank you